The Alfred Machin collection of Gallé stencils and pouncing patterns.

In February 2022, the auction house Anticthermal, in Nancy, sold a rather interesting small collection of 29 drawings apparently coming from the Établissements Gallé and belonging to the family of a former Gallé worker.1 As it is usually the case, the seller opted to keep anonymous, and most of the items were labelled as coming from “a collaborator” of the “Ateliers Émile Gallé“. It’s, in fact, possible that all pieces did not belong to the same original collection, but that they were aggregated in this sale, or that they were acquired separately by another collector. The case for a single provenance nevertheless looked strong enough, coming from the following observations. Most of the drawings are contemporaneous as the identification of the motives and the signatures types confirm — some of them even come from the same design for glass, as we shall see. Many are in fact stencils or pricking patterns (poncifs in French), design copies whose lines are dotted with pinholes to transfer the drawing on the glass surface. This betrays the origin of the collection as coming from a painter decorator or from another low or mid-level Gallé worker rather than from a designer. Two particular items allow narrowing the range of possibilities.

The first is a “piqueuse pour poncifs“ (lot #369), a rare mechanical apparatus used to make the pouncing patterns for the painter decorators. The sale’s notes claimed that the device used to belong to a collaborator of Émile Gallé and that it was used to make the firm’s stencils.

The second is a stencils’ pattern album labelled as coming from M. Machin’s workshop (lot #317), a designer of embroidery’s patterns in Nancy and a collaborator of Émile Gallé (for making stencils). The album is described as containing various patterns dating from 1854 to 1862.

It hardly seems a stretch to hypothesize that the different “Émile Gallé’s collaborator” mentions in the various lots’ descriptions all refer to the same individual.2, whose identity can be deduced from the Machin patterns’ album.

The drawings in the collection belong to several technical types, related to the process of designing and above all transferring the décor pattern from paper to glass by pouncing:

watercolours on paper for botanical studies and compositions, for the designs’ creation;

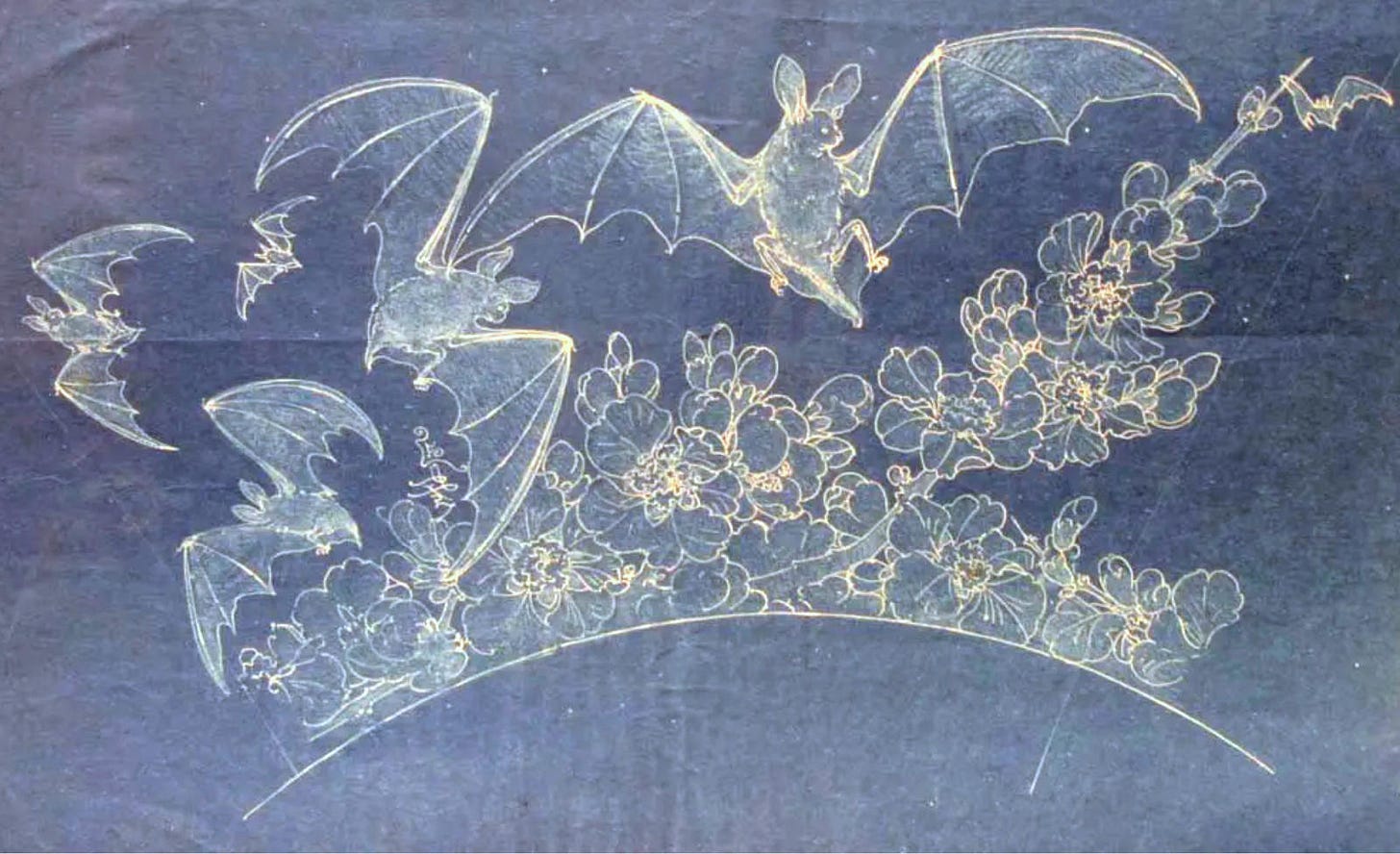

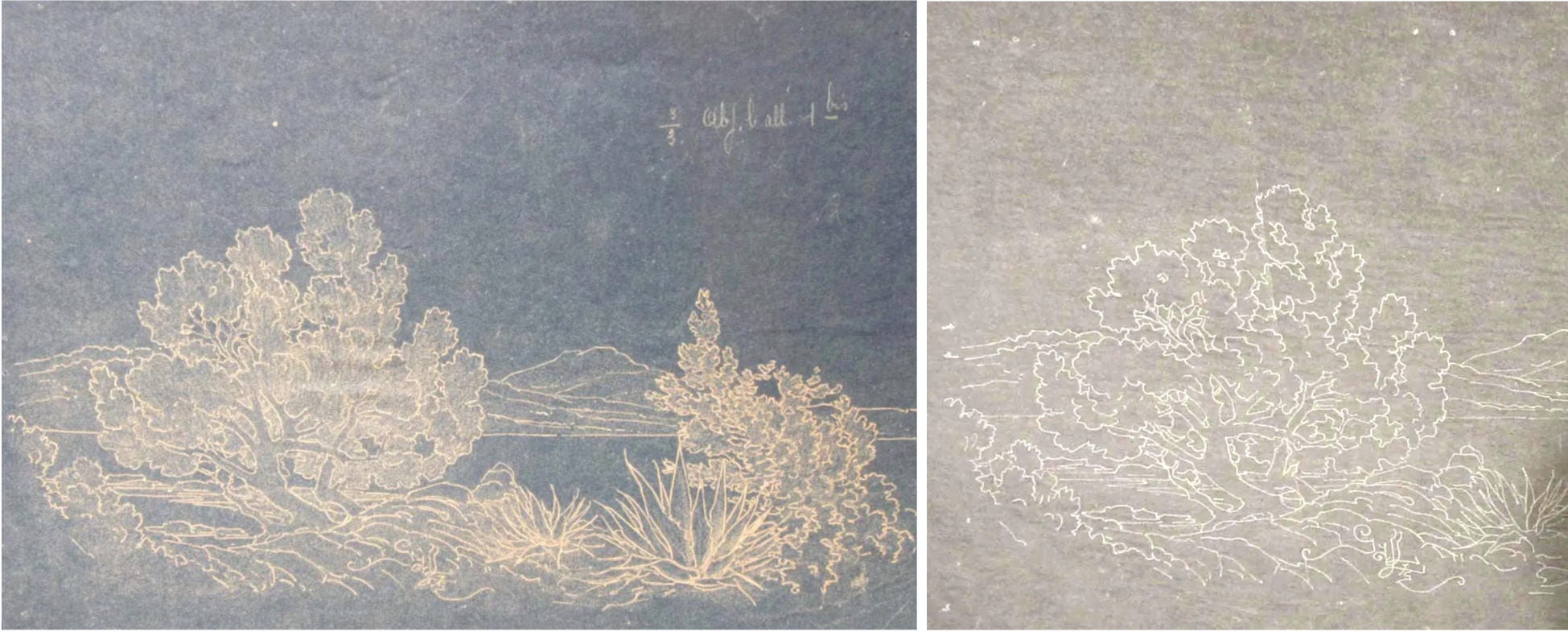

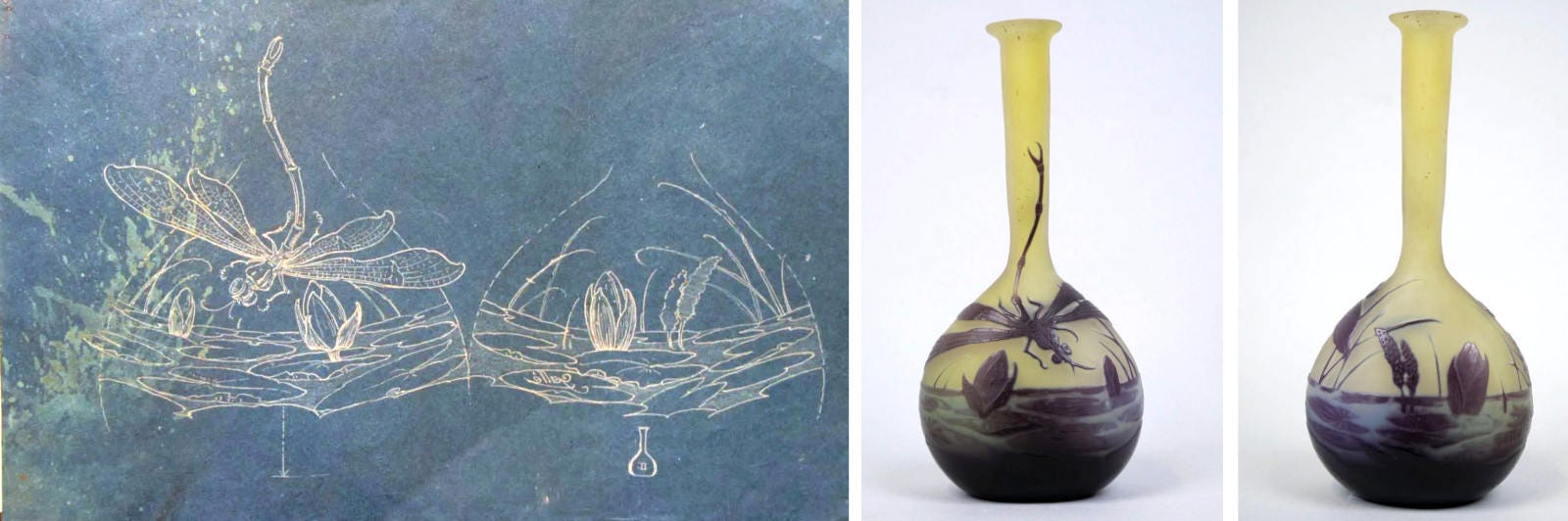

preparatory drawings of the décor by pencil or black ink on tracing paper, usually with the guiding outlines of the glass piece’s shape and a small sketch of the piece’s profile;

cyanotypes or blueprints, i.e., chemical photography or copies of the preparatory drawings, with their outlines pinpricked, when they have already been used to make pinprick patterns;

pinprick patterns on tissue paper, pinpricked outlines of the preparatory drawings (without any ink drawing).

The two last categories, the pouncing patterns, are, with the preparatory pencil drawings on tracing paper, the most frequent graphical documents surviving from the Établissements Gallé, and for good reason: they have probably been made by the tens of thousands.3 As they were cheap, simple reproduction tools, but fragile ones, easily destroyed as made. The Jean Rouppert collection (on an altogether different scale, with more than 900 drawings), which has been dispersed in several sales and auctions over the past few years, had its fair share of such documents – even though, since he was a designer, compositions, and studies represented a far larger percentage of the total than in the Machin collection. The comparison is still a useful one, since Jean Rouppert was active in the Établissements Gallé just before Machin was hired, as we shall see – in fact, their time working for the Gallé company probably overlapped more or less for a year, since Jean Rouppert chose to leave in September 1924.4 One must note, however, as a testimony of the vast number of designs made in the Établissements Gallé, that the two collections seldom match: they share a few décor (grapes, water lilies, poppies) but not their same variant, and these were among the most common themes throughout the Gallé history, so it’s hardly significant.

Alfred Machin (1875-1940), pouncing patterns’ maker for the Établissements Gallé.

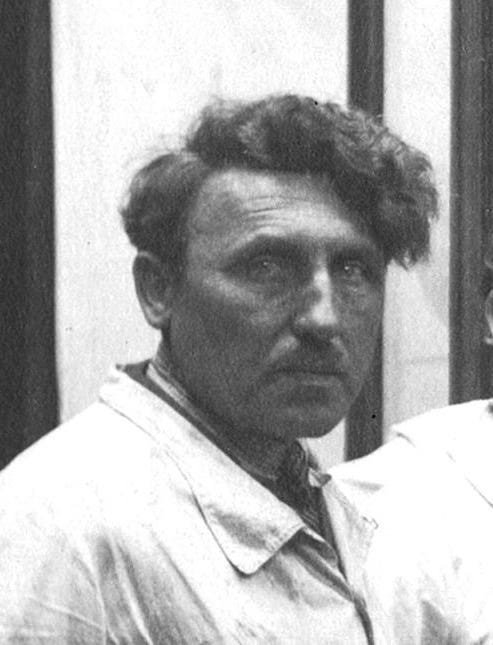

There’s only one mention of an employee named Machin in the Établissements Gallé, and it’s a late one. Jean Bourgogne, Émile Gallé’s only grandson and the universal heir of the Gallé family in 1981, gave the Musée d’Orsay in 1986 a print of a photograph, taken by Hippolyte Dubois, picturing the reception of the aviator Marc Bernard by the Établissements Gallé direction in May 1927.5 This is a crucial document for identifying the main actors in the company at that time. Jean Bourgogne took care to write down on the print the names of most of the Gallé personnel shown in the photograph and to give their occupation: the first one on the left is labelled as “Machin (son vrai nom), chargé de faire les [piqués]”.6 Le Tacon published another print of the same photograph in his important booklet on the Usine d’art Gallé à Nancy, with a more correct description, giving Machin as the employee in charge of the stencils’ workshop.7 But he failed to include him in his various lists of Gallé employees, probably for a lack of information and because Machin was a late comer to the Établissements Gallé, in the 1920s. The man pictured in 1927 looks young enough to be in his forties. He is not one of the old Gallé collaborators like Émile Lang or Auguste Herbst. So, who is this Machin? His name, by the way, literally translates in English as “What’s-His-Name”, hence the dry joke or the genuine concern by Jean Bourgogne that he may be misunderstood, prompting him to add that it was “his real name” to the print’s description.

The Annuaire administratif statistique historique de la Meurthe-et-Moselle for 1922 lists two embroidery designers or draughtsmen, named Machin in Nancy.8 They were brothers, the sons of Antoine Machin (05.11.1837-?), himself an embroidery designer too.9 They evidently took over their father’s trade and perhaps his business:10 the embroidery pattern album, which failed to sell in Anticthermal’s initial auction, must have been his, if the reported dates (1854-1862) are correct. The existence of such a personal album could suggest he was indeed his own boss. The date of his death remains to be determined, but he was at the minimum long since retired, if not dead, by 1922 (he would have been 85 years old). That his two sons have separate addresses in the Annuaire means that they did not work together, a hypothesis which is confirmed by the crumbs of information one can glean from the public records.

The first of the two brothers listed in the Annuaire is Marius Machin (1881-?), living on 5, Saint-Dizier street. Population census for 1921 and 1926 show him as a married man with four kids (at that date), the oldest one being born in 1908 (so too young to be of interest here). While Marius Machin does give his occupation as “dessinateur de broderie” in 1921 (no company listed), he had resigned from his job by 1926 to become a handler for Drouard, a mechanical workshop in Nancy, before returning to his previous occupation by 1931 (still no listed employer). In the 1936 census, he gives both trades, embroidery draughtsman and handler for Drouard, while one of his sons joined him in the latter company. This back and forth evidently suggests that Marius Machin had trouble earning a living in his preferred occupation, and that he had to supplement it by some menial job at Drouard’s. One can rule him out as the Machin collaborating with the Établissements Gallé, for the information would appear on the census.

The second Machin known from the 1922 Annuaire is Alfred Machin (1875-1940), born in Nancy, residing on 21 République street in 1921, a neighbourhood favored by the Gallé workers — the designer Jean Rouppert, for instance, was living down the same street (number 72) at the time, as was Paul Nicolas, whose own glass studio was located here as well. It’s no surprise, then, that the 1926 census lists Alfred Machin as working as a draughtsman for the Établissements Gallé: he is therefore the man in the 1927 picture.

What remains to be determined is the exact timeframe of his employment by Gallé. In 1921, Alfred Machin self declares to the census as an embroidery draughtsman, being his own boss, presumably working with his eldest son, “Maurice”, also an embroidery draughtsman, born in Nancy in 1896 — there is certainly a mistake here, since all the subsequent census lists (1926, 1931) designate this son as Jean or Antoine, which are indeed his first-names in the birth registry. In the late 1920s, anyway, Jean Antoine went on working as a draughtsman for the Barjon Frères underwear company (8, Fabriques street in Nancy).11 It looks like his father closed down his workshop between 1922 (when he is still listed in the Annuaire) and 1925 to take charge of the stencils making department in the Gallé factory. In the 1931 census, Alfred Machin drops the mention of the Établissements Gallé in his stated profession: in August that year, the Gallé direction laid off most of the workforce and Machin evidently was part of the dismissed. Pending further investigation, one can estimate that Alfred Machin worked for the Établissements Gallé less than a decade, from ca. 1923 to 1931. Crucially, these were the years during which Jean Bourgogne joined the factory staff and made a point to work in all departments, to prepare himself for his future role as the company’s director — he would have known Alfred Machin well enough. A last point to be made is that, as far as can be determined, Alfred Machin was the only member of his family to work for the Établissements Gallé, at least as a draughtsman.

This chronology is of paramount importance because it impacts the estimated date of the various Gallé drawings and stencils in his collection (if indeed it’s his): they should have been made in the 1923-1931 period for the most part.

Stencils or pinprick patterns making in the Gallé factory, a poorly documented matter.

At the presumed date of his recruitment by the Établissements Gallé, in 1923, Alfred Machin was already 48 years old, making his career change quite an unusually late one, for an industry that was accustomed to taking apprentices in their teens. One might ask why the Établissements Gallé, for their part, were interested in recruiting someone with no previous experience in the glass or cabinet making industry. The answer lies in the common method used to copy decor patterns across most of the applied arts industries, derived from the prick and pounce embroidery design transfer. Trained as an embroidery draughtsman, Alfred Machin was an expert in making pouncing patterns – as his personal embroidery patterns album attested – and what was needed of him in the Établissements Gallé was no different: only the destination of these pouncing patterns, to be applied on glass or wood and not on textile, was new and this had minimal impact on his job.

Alfred Machin was not the first draughtsman to come from garment design to earthenware or glass for that matter: Gengoult Prouvé, Victor Prouvé’s father, was recruited by Charles Gallé in the 1860s to create designs for his growing business as an editor.12 By contrast with Gengoult Prouvé, though, Alfred Machin was not tasked with creating decor patterns, but only to copy them on a medium the painters on glass and the wood marquetry cutters could use.

Among the different steps needed to make a cameo acid-etched vase, from the blowing of the molten glass to the polishing of the finished glass piece, the least documented ones are probably the technical drawing and the copying of the design to transfer it on the glass. There is ample documentation on the decor painting, from witnesses and workers’ accounts, as well as from photographs. The designers’ original work is also well known, from the preserved numerous watercolour compositions by the Établissements Gallé artists (Hestaux, Nicolas et al.), especially for unique artworks or small series, many of them with annotations by Émile Gallé, thus informing us on the early creative process taking place. On the other hand, the copying of these drawings to make the stencils and pouncing patterns used by the painter decorators on the glass is hardly mentioned. All that’s left from the process in the relevant literature is the word “piqué” (pouncing or pinprick pattern), a synonym for “poncif”. The documents themselves survive by the hundreds or thousands, but almost exclusively in private collections, since these ephemera, as copies of copies, are deemed of negligible value by public institutions. They are always collected as drawings, the ghosts of more prestigious but lost or unattainable pictures, with scant attention being paid to their technical aspect.

Studies of the other great French glassworks largely share this lack of information on the technique in use to transfer the designs on the vase, except for the vague mention of stencils or pinprick patterns. One of the few detailed and illustrated discussion of the design copying process appears in Jules Straub’s monograph on Désiré Christian, with the specific case of the Burgun, Schverer & Cie Greek mythological series, whose decors were copied from Walter Crane’s Echoes of Hellas drawings.13 Christophe Bardin, in the book he published from his PhD on the Daum glassworks, only mentions that the decorators were instructed to take special care of these stencils.14

As for Gallé, Philippe Thiébaut quickly dispatches the subject in his erudite monograph on the Musée d’Orsay unparalleled collection of drawings, with a single paragraph. He restricts himself to recounting the use of a sewing machine to create the pouncing patterns in numerous copies, which were then distributed to the painters of earthenware in Saint-Clément and Raon-l’Étape, as well as to the glass decorators in Meisenthal and Nancy.15 The two figures he includes are very early specimen from the 1860s and 1870s.

Bernd Hakenjos, in his posthumous thesis, very briefly discussed the matter, and included several examples of such pinprick patterns, all coming from the Rakow Library’s collection in Corning, mainly as a mean to identify and to provide a date for some decors. Other authors of Art Nouveau glass catalogues occasionally have had the same use of stencils and pouncing patterns, like Brigitte Klesse and Hans Mayr for their publication of the Fünke-Kaiser collection – again, in this case with many samples from Meisenthal.16 But, once again, it came to François Le Tacon to address the matter with a more detailed explanation, thanks to the interviews he made with four women who had worked as painter-decorators, more than half a century before, in the 1920s and early 1930s, for the Établissements Gallé.17 An additional narrative source, that was unknown to Le Tacon, is the 1913-1914 correspondence between Jean Rouppert, at the time still a painter decorator, and his soon-to-be wife, Madeleine Labouré.18 In a series of letters written in August 1913, Rouppert describes in detail his accelerated apprenticeship in the men’s decor workshop of the Gallé factory, mentioning several times the use of pouncing patterns, with some interesting, unknown before, details. After the First World War, his position at Gallé’s was upgraded to glass designer, and he became the purveyor of drawings to the worker in charge of making the pinprick patterns. But there are no written comments from him on that, which is a bit of a shame, considering the changes that seemed to have taken place at the time in this regard – as we’ll see below.

A glossed over essential part of the trade?

It’s worth noting that René Dézavelle, another Gallé decorator who left another important written testimony about his work in the Établissements Gallé, never discusses this step of the process, perhaps because he deemed it a trivial matter. But one has to wonder if another reason could not be that this would have somewhat diminished the perceived value and skill of his work. His testimony was for publication, to honor a long gone glassmaker, while Rouppert’s description was part of a private exchange.

In this regard, the lack of any pictorial document showing this stage of the painter on glass’s work is also revealing. There are at least eight published photographs of the two main painters’ workshops (the men’s and the women’s) inside the Gallé factory, either in contemporary accounts, like the article by Lanorville,19 or in more recent books, like the first edition of Le Tacon’s booklet on the Gallé factory.20 They are depicting the workshops fully manned, with several dozens of workers, men, women and children, all of them hunched over their benchwork or milling around tables laden with glass pieces. None of these decorators is seen handling pinprick patterns or applying them to the glass, even though some patterned stencils can be seen attached to their bench or spread out before them, purportedly to be used as a model. Almost all the workers have a brush in hand, and they are shown in the process of applying the protective varnish on a vase, before it is sent to the acid tanks. This latter step is, by the way, missing too from the available photographic documentation on the factory,21 which is really a shame, considering that it was one of the most important and efficient aspects of the Gallé factory. This hardly seems a likely coincidence. In spite (or is it because?) of their documentary goal, these photographs were, in fact, carefully composed – one could almost say that they were staged. According to an oral tradition, they were taken by Hippolyte Dubois, a marquetry worker in the cabinet furniture department, who doubled as the Établissements Gallé unofficial photographer:22 these pictures were therefore closely controlled in their composition by the factory’s management,23 to strengthen the company’s reputation as an Art glassmaker.

Take for instance the second picture in Lanorville’s 1913 article (see the picture above): it shows a decorator sitting in front of an impressive landscape vase, applying the varnish with his brush, almost as if he were an artist free painting a landscape on his easel. Nothing suggests to the reader that he is strictly following the outlines marked on the vase’s surface with the pouncing pattern, even though this process is discussed in some length on the following pages in the article.24 Like the omission of the acid workshop in the photographic selection, this picture tends to mitigate the industrial nature of the fabrication process. In a nutshell, part of the lack of information about the pinprick patterns and their making might derive from the image the Établissements Gallé were trying to project to their customers, and to the public in general – as did the other glassworks.

The embroidery design stitcher and its use in the glassworks.

In July 1925, the Établissements Gallé were incorporated as a limited liability company (Société anonyme par actions). During the incorporation process, they were required to submit a financial statement that included a comprehensive valuation of their stock inventory, including tools and machinery. This crucial document, registered with the Gallé family’s solicitor’s office, provides a detailed list of every piece of equipment in the factory at that time. By reading the list, one can easily trace the accountant’s progress from building to building, room to room, noting the various tools and equipment. Regarding the stencils and pinprick patterns’ office, the list specifies only one drawing cupboard and one (and only one) stitching or pricking machine (« machine à piquer »), for a Fr 65 estimated value. Was this machine the one part of the Machin estate sold in 2022? The auctioneer certainly thought so, and it’s a strong possibility but not a certainty, for Alfred Machin most probably left the Établissements Gallé in 1931, several years before they completely shut down, and the remaining decorators would still have needed new pouncing patterns to work on.25 There isn’t any doubt, however, that the Établissements Gallé’s pricking machine, if it were a different one from Machin’s, belonged to the same class of devices that had changed very little over a century since their original design.

![“Machine à piquer les dessins” by Barthélémy, in art. “Dessin industriel”, Charles Laboulaye, Dictionnaire des arts et manufactures, description des procédés de l'industrie française et étrangère, Paris, 1886 (6th edition), vol. A-D. [online], fig. 651. [online] https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k30411663/f1223.item “Machine à piquer les dessins” by Barthélémy, in art. “Dessin industriel”, Charles Laboulaye, Dictionnaire des arts et manufactures, description des procédés de l'industrie française et étrangère, Paris, 1886 (6th edition), vol. A-D. [online], fig. 651. [online] https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k30411663/f1223.item](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!WEQ-!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fe341807b-8d45-4395-94c9-f86922b1be34_1844x1846.jpeg)

The invention of a mechanism to speed up the transfer of a drawing to a pounce pattern then used to mark another surface, primarily a piece of fabric, but soon enough almost any object like a piece of ceramic, glass or wood, is closely linked with the development of the textile industry in the early 19th c. Its design is akin to a simplified sewing machine, and the development of both devices is roughly contemporary. Earthenware manufacturers and glassworks quickly benefited from this innovation, concurrently claimed by many inventors in different European countries. The prototype in France went back to the invention by one Barthélémy, in 1824, of a machine à piquer les dessins. “It essentially consists of a spring whose play sets in motion a needle enclosed in a small tube, which the worker passes successively over all the lines in the drawing. In 1830, the same inventor devised a pedal mechanism with a flywheel that set in motion a series of pulleys, the last of which had an eccentric axis and raised and lowered the quilting needle by rotating it.”26 Many followed other the years, with their own versions of this apparatus. For instance, in 1844, M. Dorléans, from Paris, was noticed in the Exhibition of products from French industry for his machine à piquer les dessins de broderie, i.e., “a pricking machine for designs to be reproduced by pouncing, i.e., using a coloured dust deposited through the holes made in the paper by the machine”.27 Garment makers in Nancy and its area were quick to claim this technical innovation: as early as 1835, a local clockmaker named Humbert was disputing the paternity of a similar mechanism to an embroidery workshop from Metz.28 As the Machin device makes clear, other industries using the prick and pounce pattern copying method soon saw their interest in this technology.

The machine belonging to Alfred Machin was made by Prestat, apparently a major manufacturer of these, in Paris, at the end of the 19th c. The Prestat device is very close to the original prototype by Barthélémy, only more compact, with the wheel and the retractable pedal enclosed in a wooden box. The horizontal balance is fitted with a counterweight to offset the charge of the rod holding the needle. The length of the balance and the position of the counterweight are adjustable. This allows large tracings to be stitched with a wide passage on the operator’s table. This was an essential feature in the Gallé factory where some outsize patterns, on glass for the tallest vases but more so on wood for some cabinet furniture, were required. The stitcher guides the needle over the lines of the drawing on tracing paper, superposed with several sheets of tissue paper, which are thus pricked with the tiny holes needed to make the pouncing patterns for the painter decorators.

Working with the pouncing patterns in the glass decor workshops.

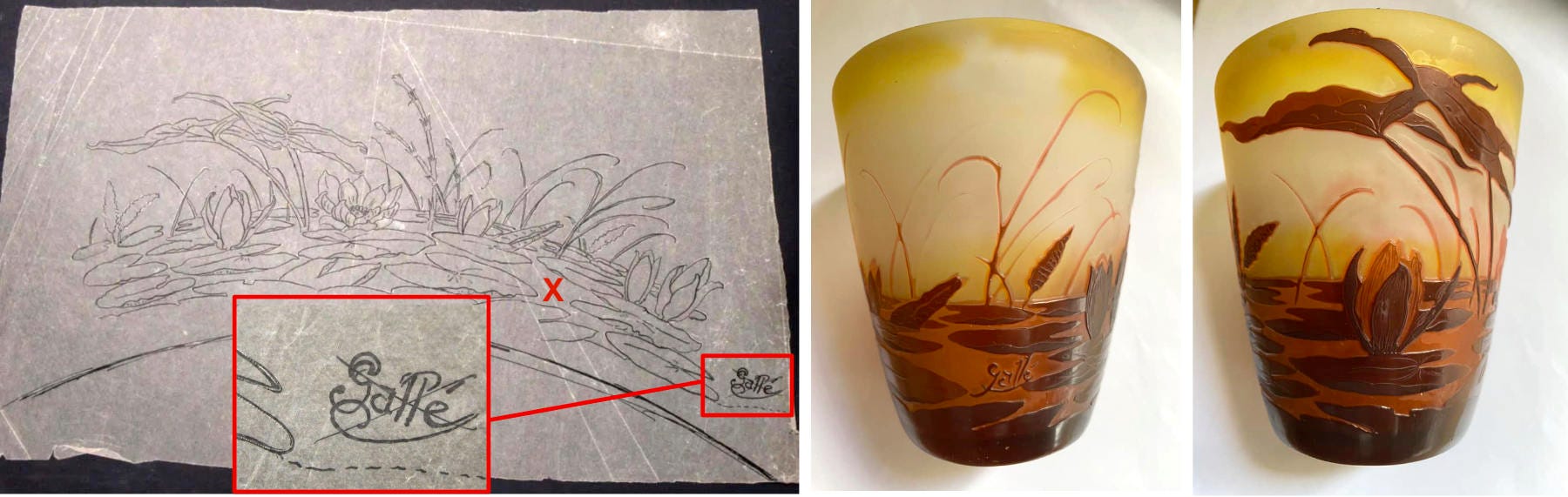

The pricking machine operator was part of the drawing studio’s personnel – a fact confirmed by the official factory photograph shown above, where Alfred Machin stands next to the two main designers for glass at the time, Georges Déthorey and Théodore Ehrhart. He received from them the drawings he was tasked to make pouncing patterns from, with his pricking machine. These drawings were either hand-drawn copies on tracing paper from the final design artwork prepared for a given glass shape, or blueprints, i.e., photochemical copies made from these tracings. By using tissue paper as the medium for the pouncing paper, the pricker could go over a stack of ten sheets at once, and thus make as many pouncing patterns. The Machin collection contains several of these flimsy drawings, with sometimes both the blueprint and the pouncing pattern for a given design, like the specimen above, a landscape pattern for a lamp hat.

These pouncing patterns were kept under close control and the decorators were not supposed to take them out of the workshops, to prevent competitors from using them for counterfeit products.29 This control worked only so far, as many Gallé drawings and pouncing patterns found their way out of the factory, well before it was closed for good: it was difficult to control every worker leaving the company, and the many departures in the early post-war period, especially those of designers like Nicolas and Rouppert, for instance, most likely resulted in the spiriting away of such material – these were after all their drawings to begin with, even if, from a legal perspective, their intellectual property was very much the Établissements Gallé’s. It’s not clear if Nicolas and Rouppert received special permission to keep some of these, but rather unlikely.

In the decor workshop, each painter received the pouncing pattern corresponding to the series he was tasked to work on. He or she fitted the vase onto a horizontal wooden rod fixed to the underside of his workbench, acting as a support on which he could turn the piece (see the pictures above). He then applied the pattern on the glass surface and pounced it with a small cloth pad (the poncette), passing some talcum powder through the pattern’s tiny holes, and thus creating the white outline of the desired motif. He retrieved the pouncing pattern and, in the case of cameo glass series, proceeded to paint the delineated areas with a special varnish, whose main component was Judea bitumen, to protect them from the bite of acid.

This painting being the main task of the decorators, it’s often the only focus in the few existing technical descriptions of their work. The application of the pouncing pattern, however, was not always as straightforward as it would seem, especially with small and medium-sized vases. The first step was to ensure that the provided pattern was the right one, and that it had been correctly made to fit the shape. With up to 15 or 16 different shapes planned in the case of the most popular series, each often available in 2 or 3 sizes, mistakes would be easy to make. That’s why the stencil usually featured a small outline of the intended piece as an identification mark of sort, sometimes with additional annotations, like on the Dragonfly over water lilies blueprint above: the Roman numeral II inside the vase’s sketch identifies a variant shape from the usual small soliflore. In other glassworks, the system would go much further: Paul Nicolas had each stencil penned with not only the small sketch of the piece’s shape, but also its reference number and its measurements. Furthermore, the biggest glass pieces, like some lamps, needed several pouncing patterns. In that case, they were given an abridged designation and numbered, like the “Ab[at]j[our] b[oule] all[ongée] 1bis” shown earlier in this section, which is the 3rd out of 3 patterns for a lamp hat with a landscape decor (which I could not identify).

Mistakes could still happen with the pouncing pattern incomplete or ill-fitting the shape, which required the painter to fetch a new one or to remedy himself to the matter. At Daum’s factory, the instructions were clear in that case: the foremen had to be notified to monitor any corrections. A technical note was issued to the decorators with the stencils, bearing these instructions: “Lorsqu’un poncif est trop petit ou trop grand pour la pièce à décorer, consulter automatiquement le contremaître pour les modifications à faire.”30 There’s no evidence of such a formal notice in the Gallé factory, but its foremen were exercising a strict control there as well on the matter. On the other hand, it looks like the painters could be trusted, perhaps under their guidance, to correct or to complete the drawing themselves.

This is what transpires, in any case, from some interesting remarks regarding the use of the pricking patterns, made by Jean Rouppert, while describing his apprenticeship in the decor workshops in 1913. Commenting on the difficulty of his new job, he wrote:

Ces vases sont biscornus. Ils ont des formes d’amphore, de demi-lune, de tronc d’arbre, de demi-sphère, de cône, etc. On fait des bonbonnières, des abat-jour, des lampes, des godets, des porte-cigares, des pots, des suspensions, des globes, que sais-je. Arriver à décalquer en ces trous, ces bosses et ces congés demande plus que de l’adresse, il faut aussi savoir dessiner pour faire les raccords, créer des feuilles ou des fleurs et remplir les vides. Ceci avec un crayon bleu spécial.31

This important testimony underlines the drawing skills needed by the painter decorator, for this preliminary step of his work. Compared to the shapes in use before Émile Gallé’s death, the Établissements Gallé had a still diverse but simplified line-up, insofar as the complexity of the volumes was concerned: gone were the applied parts or the scalloped openings and similar naturalistic effects in most shapes. However, the application of the drawings on the three-dimensional objects still required some elaborate pattern cutting, which are outlined on the preserved stencils, like those for the two soliflores shown above. These hint at the difficulties recounted by Rouppert. This explains in part – with the painting itself of course – why the apprentices received drawing lessons in a special in-house school. Most of the painter decorators had no such education or practice (unlike Jean Rouppert, an accomplished if self-taught draughtsman) and still needed it, to properly use the pouncing patterns to begin with.32

After its initial application, the pouncing pattern was still needed by the decorator, in case of the accidental erasure of some of its white markings on the glass. This additional use of the patterns, during the painting, explains why some of them bear partial orange or brown stains from the varnish, like on the Clematis pattern above. After the vase had been etched in the acid-tanks, rinsed, cleaned and dried, it came back to the decorators for a second – and occasionally a third or even a fourth – coating of varnish, to delineate additional details of the pattern.33 For each of these tones, the decorator used the same pouncing pattern over and over, until the wear and tear of these fragiles sheets of papers forced their replacement. The mechanized production of these pouncing patterns was therefore a necessity, given the sheer number the factory needed to feed its workshops.

Additional lessons from the Machin collection of preparatory drawings

Blueprints or cyanotypes

The study of the Machin collection provides valuable insights into the design copying techniques employed during the Établissements Gallé’s latter operations. One such technique involves the use of photochemical copies, specifically cyanotypes or blueprints, to expedite the copying of stencils before creating pricking patterns. This technique, invented in 1842, utilizes a special paper coated with a chemical solution (made from ferric ammonium citrate, ferric ammonium oxalate, or potassium ferricyanide) sensitive to ultraviolet light. The paper then acts as a contact print, producing a negative of the original image. A pencil or ink drawing on transparent paper is fixed to the cyanotype and exposed to sunlight, triggering a reduction chemical reaction that turns the paper a deep blue, except where the drawing lines mask the paper. The paper is then developed by simply washing it with water, resulting in a white-on-blue print. If the original image has been placed face down on the cyanotype, with the ink in direct contact with the coating, the resulting copy appears reversed, as seen in all blueprints in the Machin collection which feature reversed Gallé signatures (see for instance the Mk VIII signature on the Pavots blueprint below).

By the end of the 19th century, this technique had gained widespread adoption among applied arts industries, particularly for copying schematic designs such as architectural or technical drawings. Its simplicity, economy, and speed over hand-drawn tracings made it an ideal choice for preparing pouncing patterns. However, hand-drawn tracings remained a prerequisite, and the opacity of cyanotypes posed a significant challenge. They could not be used as pouncing patterns, potentially hindering their broader adoption and favoring traditional drawings on tracing paper.

The Rouppert collection, comprising only four blueprints out of approximately 900 drawings, represented a negligible proportion compared to the other drawing techniques and mediums used in the Gallé design studio. In contrast, the Machin collection, which had a more modest collection of 11 blueprints out of 33 drawings in total, exhibited a significantly different distribution. It’s plausible that the varying roles played by Rouppert, the designer, and Machin, the pricker, contributed to this disparity. Rouppert was responsible for composing and copying the designs, while Machin utilized them to create the pouncing patterns. However, the identity of the individual responsible for creating these blueprints remains unknown.

Another plausible explanation, in my opinion, could be chronological. The introduction of cyanotypes might have been a late innovation, influenced by various factors. One factor could have been the industrial-scale ramping up of glass production in the mid-1920s. The Gallé factory required more stencils and pouncing patterns than its design studio could produce, and blueprints served to expedite the copy-making process. Another factor, related to the first one, was the Gallé factory’s difficulty in recruiting new workers during that period. In a private written testimony, Jean Bourgogne mentioned that it was « very difficult to recruit draughtsmen/designers » for the Établissements Gallé in the 1920s. He didn’t elaborate on the reasons, but several possibilities come to mind. First, there was a significant exodus of seasoned Gallé designers at the turn of the 1920s, a crisis I have documented elsewhere.34 The Établissements Gallé faced significant challenges in the 1920s due to the death of Louis Hestaux (1919), and the resignations of Paul Nicolas (1919), and Jean Rouppert (1924). These losses left the company shorthanded and in need of replacements. Théodore Ehrhart and Georges Dethorey eventually took over, but the exact date of their appointment is unknown, likely occurring around 1925 after a substantial period of vacancy.

Beyond the personnel issues, the Établissements Gallé’s reputation as an employer took a hit during this time. They openly abandoned their high-art pretences and focused solely on productivity. This shift in priorities may have made it challenging to recruit talented designers.

Furthermore, the rise of ambitious new art glass companies in Nancy, Delatte, and the Cristalleries de Nancy further exacerbated the problem. These companies required skilled draughtsmen and glassworkers, leading to intense competition for available talent.

It’s perhaps in response to these challenges that the Établissements Gallé introduced blueprints. This move was likely a response to a shortage of skilled manpower or a pressing need for more copies of designs to create pricking patterns. This adoption of blueprints represents a striking shift towards an industrial technique and can be compared to what was happening in other departments of the factory during the same period. For instance, mechanical blowing was introduced for the new relief series in 1925.

Signatures on the pouncing patterns

The 4 signatures present on the blueprints support this chronological hypothesis: 3 of them belong to the Mk VIII types (the horizontal or the vertical one), which I had first tentatively dated from circa 1927, before recognizing that it might have been introduced earlier, in 1924. Either date falls in the period where Alfred Machin was responsible for making the pouncing patterns. The fourth signature, on the Dragonfly over water lilies soliflore (see the picture in the previous section), is an Mk III one: this supports in turn a revision of this signature’s chronology, which either may have been phased out during a longer period than I proposed, or may have been reprised in the mid or even late 1920s. More data will be needed to make this determination, but it is certainly true that a few Plumsrelief vases (from 1925 and later), for instance, feature this signature type.

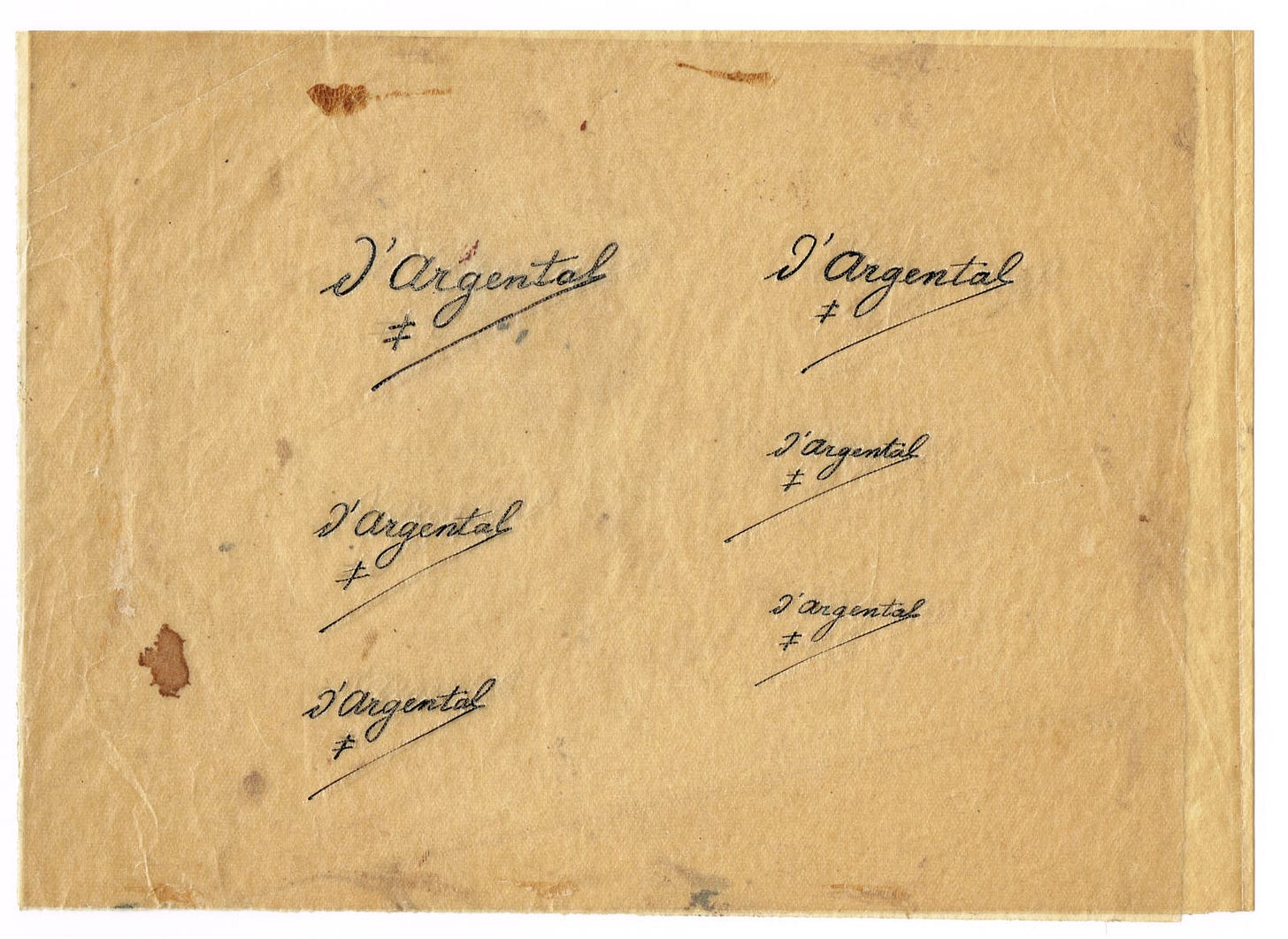

The pouncing patterns and drawings on stencil paper in the Machin collection almost all sport a signature, from the expected types for this period – Mk IV, Mk V and Mk VIII – with a single missing notable exception, the Mk VI one, which was nonetheless the most common after 1925. A few pouncing patterns lack any signature, which is unsurprising, for it’s well known from oral testimonies as well as from the available specimens that they could be added later: they were either freely drawn by hand, especially on the smaller pieces, or made using a separate pouncing pattern. While I haven’t seen any of those from the Gallé factory, the practice is also attested in Paul Nicolas studio, as shown by the pricked pattern above, featuring 6 copies in different sizes of the same D’Argental with Cross of Lorraine signature. It would have been made around the time Nicolas switched signatures from the generic Saint-Louis one to this new type, in 1920. The same kind of patterns were also made in the Établissements Gallé.

It reinforces the importance given to the correct drawing and positioning of the mark. We know that, in the Gallé workshops, foremen were checking on the correct drawing of the signatures twice a day, on the morning and the afternoon.35 When they deemed the result poor, the painter had to erase the signature with turpentine, and to draw it anew freely by hand, under direct supervision, or with this kind of pouncing pattern.

An interesting trace of this tight control over the signature subsists in the Machin collection of drawings. The pouncing pattern for a Sagittarius and waterlilies series bears a crossed out signature (see the picture above). As made specimen of the vase can attest, this signature is not drawn in its proper place, which I marked with a red X on the drawing, inside the decor pattern, but on its side, where it was probably added because it was missing. It was to be added later with one of the two just discussed methods. The crossing out does not indicate a wrong placement, but a wrong type: the mark is an awkward mix of the Mk III and Mk V signatures, with the Pi-like double Ls and the underlining stroke sectioning the capital G. This tentative new mark was replaced by more common types on the vase.

Conclusion: The Fictive Artistry of the Painter Decorator

The Machin collection offers a fresh perspective on the pivotal steps involved in creating pouncing patterns and applying them to glass at the Gallé factory. It’s not surprising that we lack knowledge about these processes, as the company had no interest in promoting them. The allure of Gallé-decorated glass vases lies partly in the prestige carefully cultivated and maintained around them, the association with the renowned artist, and the pretense that these industrial series were considered art pieces, prized luxury items, especially for the largest and most intricate ones.

The collection suggests some alterations in the process, including the introduction of blueprints, though it’s challenging to assess their significance from this limited sample. Nevertheless, it supports the general notion that Établissements Gallé underwent a more streamlined industrial operation, seeking innovative methods to enhance productivity at the expense of their artistic and craftsmanship heritage.

© Samuel Provost, 5 November 2024.

Bibliography

Bardin Chr. 2004, Daum, 1878-1939: une industrie d’art lorraine, Metz, Serpenoise,

Dézavelle, R. 1974, The history of the Gallé vases, Glasfax Newsletter, Montréal, septembre 1974.

Hakenjos, B. 2012, Emile Gallé : Keramik, Glas und Möbel des Art Nouveau, Munich, Hirmer, 2 vols.

Klesse, B. Mayr, H. 1981, Glas vom Jugendstil bis heute: Sammlung Gertrud und Dr. Karl Funke-Kaiser, Köln.

Lanorville, G. 1913, “Les cristaux d’art d’Émile Gallé”, La Nature, 41, nr 2075, p. 209‑212.

Le Tacon, Fr. 1993, “Les techniques et les marques sur verre des Établissements Gallé après 1918”, Le Pays Lorrain, vol. 74, nr 4, p. 203-217.

Le Tacon, Fr. and De Luca, F. 2023 (2), L’usine d’art Gallé à Nancy, Nancy, Association des amis du Musée de l’école de Nancy, second edition.

Muller, R. and Rouppert, J. 2007, Jean Rouppert, un dessinateur dans la tourmente de la Grande guerre, Paris, L’Harmattan.

Musée de l’École de Nancy, Thomas V., Sylvestre F., Olivié J.-L., 2014, Émile Gallé et le verre: la collection du Musée de l’École de Nancy, Paris, Somogy éditions d’art.

Provost S. 2018, “Les Établissements Gallé dans les années vingt : déclin et essaimage”, Revue de l’Art, 199, 1, p. 47‑54.

Straub, J. 1978, The Glass of Désiré Christian, ghost for Gallé, Chicago.

Thiébaut, Ph. 1993, Les dessins de Gallé, Paris, Réunion des musées nationaux.

How to cite this article : Samuel Provost, “From paper to glass: design copying techniques in the Établissements Gallé. The Alfred Machin collection of Gallé stencils and pouncing patterns”, Newsletter on Art Nouveau Craftwork & Industry, no 30, 6 November 2024 [link].

Footnotes

It seems particularly important to record this sale because, quite unfortunately for researchers and collectors alike, the auctioneer chooses not to publish any formal catalogues of its sales nor does it maintain proper archives on its barebones website. This is all the more regrettable, since, as the premier auction house in Nancy, Anticthermal frequently puts on sale some quite remarkable pieces from the École de Nancy designers. In this case, thankfully, I was able to attend the pre-sale exhibition as well as to download the auction house’s own pictures — my thanks go to Me Teitgen for allowing me to use them on this newsletter.

It was in fact confirmed to me in a short conversation I had with Me Teitgen, without disclosing her client’s name of course.

Considering there were at least 1.3 millions Gallé glass piece made, this is an understatement, since a 1:130 ratio between poucings and glass pieces is far too low.

The date is given by a certificate of employment in the Établissements Gallé for Jean Rouppert, signed by Émile Lang, 15 Septembre 1924 (Rouppert family archives).

Orsay Museum, PHO 1986 71 127.

Here the Orsay file is faulty (indicating “pierres” instead), as it is in several other instances with the spelling : the curator in charge of filing the description had some trouble reading Jean Bourgogne’s handwriting — it’s “Dethorey” not “Detherey”, “Perdrizet” of course, not “Perdriget”.

Théodore Ehrhart’s name is mispelled (“Erard”) but that was already Jean Bourgogne’s mistake. Le Tacon, De Lucca [2001], p. 28.

p. 462.

See their genealogy on Geneanet.org.

I could not find if Antoine Machin was a small business owner or if he was employed by a larger company. His address is 16, Saint-Thiébaud street in 1875, according to the birth certificate of his second son, but I could not find him in the 1872 and 1876 census in that street.

Jean Machin had a son, Jacques, born in Nancy in 1928 and deceased on 15 August 2011, who worked in a couture house in Paris and Nancy, and was a painter and a sculptor. He seems therefore the prime candidate for the transmission of his grandfather’s archives from his time at Gallé’s: L’Est Républicain, 19 August 2011.

Le Tacon, De Luca, L’usine d’art Gallé, Nancy, 2023, 2nd ed., p. 17.

Straub 1978, p. 47-48.

Bardin 2004, p. 198.

Thiébaut 1981, p. 37-38.

Klesse and Mayr 1981, p. xviii-xlii.

Le Tacon 1993, p. 209.

Muller 2007, p. 61-76.

Lanorville 1913.

The second edition (2023) has a few pictures missing, compared to the first one.

The only depiction of the acid tanks I could find is the wood marquetry detailing the different categories of Gallé workers that Auguste Herbst designed for the display case ordered by the Musée des Arts et Métiers. But even this composition lacks the making and use of the pinpricks patterns.

Le Tacon, De Luca 2023, p. 17.

This goes beyond the scope of this article, but the date and occasion for which they were taken makes it clear.

Lanorville 1913, p. 211-212.

Among several hypothesis, Alfred Machin could have bought back his old machine at the fire sale of the factory, in June 1936, if he had left the company without it in 1931.

Exposition publique des produits de l’industrie française, Rapport du jury central, t. 2, Exposition des produits de l’industrie française en 1844, Impr. de Fain et Thunot (Paris), p. 448: “machine à piquer les dessins qui doivent être reproduits par l’opération du ponçage, c’est-à-dire au moyen d’une poussière colorée déposée au travers des trous faits dans le papier par la machine.”

Le Tacon 1993, p. 209.

“If a pouncing pattern is too small or too large for the part to be decorated, automatically consult the foreman about the changes to be made.” Bardin 2004, p. 198.

Muller 2007 p. 63: “These vases are twisted. They are shaped like amphorae, half-moons, tree trunks, half-spheres, cones and so on. We make candy dishes, lampshades, lamps, cups, cigar holders, pots, ceiling fixtures, globes, you name it. Pouncing in these holes, bumps and fillets requires more than skill; you also need to know how to draw to make the connections, create leaves or flowers and fill in the gaps. All this with a special blue pencil.”

On the decorators’ lack of formal drawing skills before entering the Gallé factory, see Le Tacon 1993, p. 216-217. Further proof comes from Dézavelle’s poor drawings in this mémoire.

Le Tacon 1993, p. 211.

Provost 2018.

Le Tacon 1993, p. 209.