A posthumous homage from Émile Gallé to Marcelin Daigueperce

Looking for a missing verrerie parlante with a quote from Saint John's Gospel

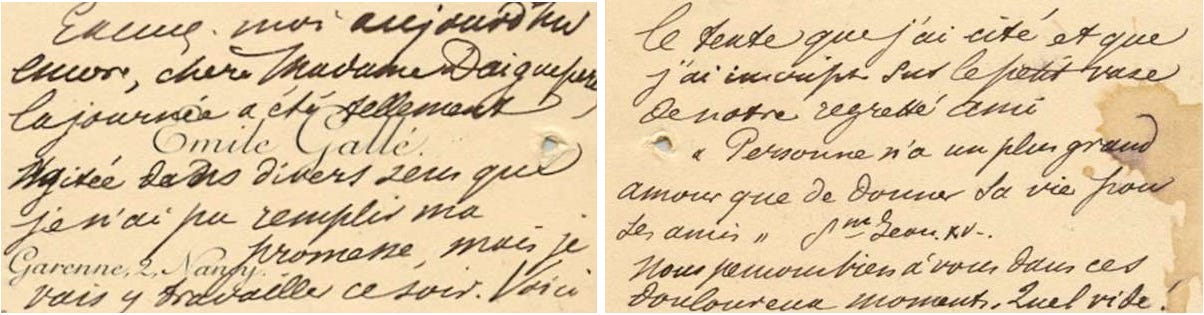

The 119th anniversary of Émile Gallé’s death, on the 23rd September 1904, is the occasion to highlight the great care the artist put into paying homage to his friends and collaborators after their or their loved ones’ passing. One such occasion is recalled by a small document that did not garner much attention since it failed to sell, it seems, at least twice in recent auctions (on 10.30.2019, lot 0257 and on 03.15.2023, lot 1151) – for all I know, it might still be available at the hour of this writing. The document is a specimen of Émile Gallé’s visiting cards, bearing his name and address in print, with a short handwritten message, spanning both sides of the card. Émile Gallé’s writing is easily recognisable – if not always perfectly legible –, and, while being unsigned and undated, the letter’s authenticity is assured. The auctioneer could not identify the message’s recipient and therefore was unable to assess the importance of the occasion: the lot’s description’s states that Émile Gallé was writing, “evidently to a client”, to assure her he would “fulfil his promise [of completing a funeral urn for a mutual friend] for the following day”, also confirming the text he had had inscribed on the vase as a quote of Saint John’s Gospel. This doesn't seem right on several counts, as a careful historical analysis of the text will show.

Identification of the recipient as Adolphine Daigueperce

The card reads as follows :

Excusez-moi, aujourd’hui encore, chère Madame Daigueperce, la journée a été tellement agitée dans divers sens que je n’ai pu remplir ma promesse, mais je vais y travailler ce soir. Voici le texte que j’ai cité et que j’ai inscript [sic] sur le petit vase de notre regretté ami : « Personne n’a un plus grand amour que de donner sa vie pour ses amis » St Jean, xv.

Nous pensons bien à vous dans ces douloureux moments. Quel vide !1

Émile Gallé is writing to one Madame Daigueperce, whose family name should be familiar to anyone bearing an interest in the Gallé history : the Daigueperce, father and son, were the main Gallé collaborators in Paris, the managers of the company depot, through which went more than half of the company’s sales. Émile Gallé had appointed first Marcelin Daigueperce, on May 10th, 1879, as his representative, in replacement of one Charles Vilain, to take charge of his depot2. It was then located on 34 rue des Petites-Écuries (before it was moved to the nearby 12 rue Richer address, in July 1886), in the 10th arrondissement, near the Sentier district, known for its manufacturers and craftsmen workshops. Marcelin’s son, Albert, born in 1873, became his apprentice as early as 1889, helping his father setting up Gallé’s exhibition in the Paris Exposition universelle that year3. At his father’s death, in 1896, he became, in turn, Émile Gallé’s depot manager, a role he kept well after his employer’s demise, until he was laid off by Paul Perdrizet in 1920.

In theory, the « Madame Daigueperce » Émile Gallé is writing to, could be either Marcelin’s wife, Marie Adolphine Lacour (b. 1843), whom he married in 18684, or Albert’s one, Julie Pendaries (b. 1872), espoused on May 21, 19045. In reality, this latter mariage was much too close to Émile Gallé’s death to allow any kind of personal contact to happen between the artist and the young bride – it’s not sure if he even met her. It follows Marie Adolphine Daigueperce must have been the visiting card’s recipient.

But why would Émile Gallé write to her rather than to her husband, Marcelin, or to both of them as a couple? From the little we know about her, she did not seem to have had any role in her husband’s business, nor did she have any particular interactions with his boss. Who could be then the common “late friend” Émile Gallé had promised her to pay a special tribute to? The simplest answer is that it was her husband, Marcelin. This fits perfectly with the message’s ending, suggesting the departed was someone very close to both of them. The final exclamation “Quel vide !”, in particular, hints at a common staggering loss: this was someone Émile Gallé knew very well.

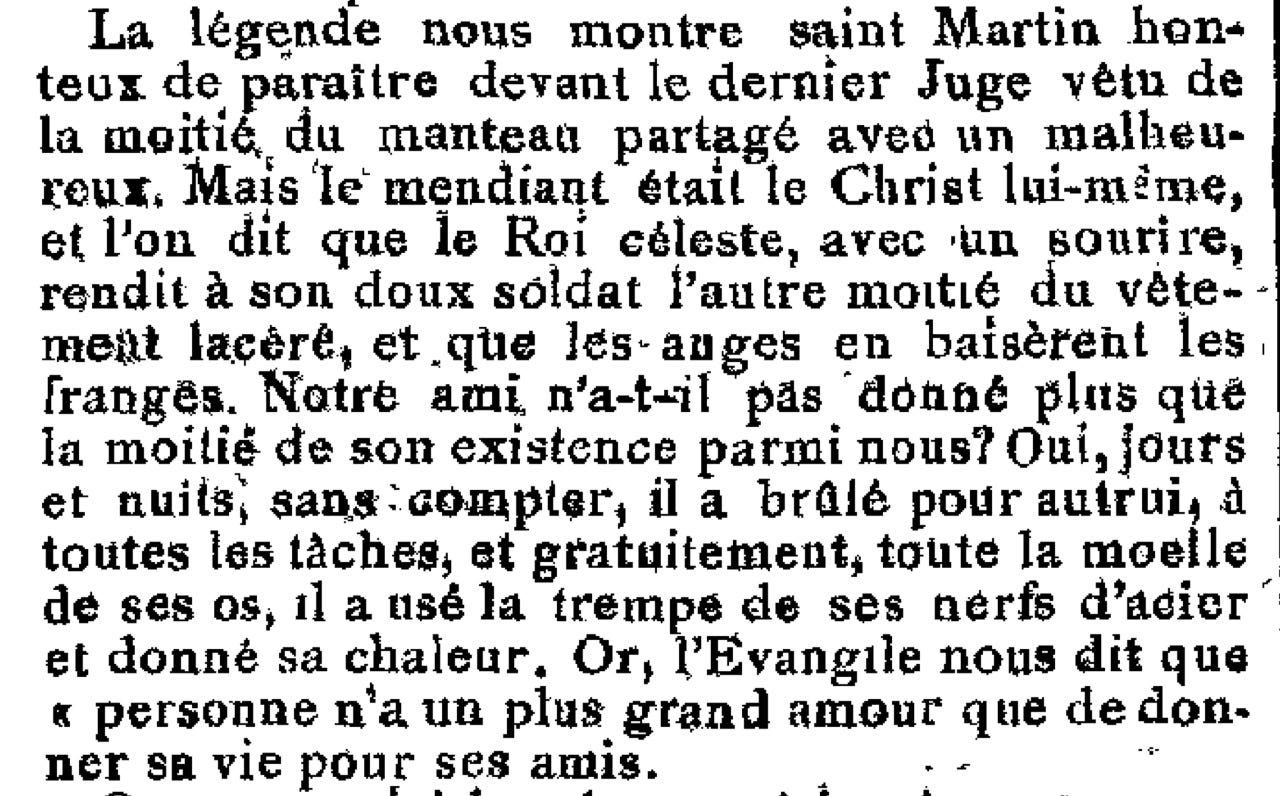

It was only natural that Émile Gallé would have a special memorial gift made in honour of his long-standing employee and advisor, a man who had played a significant part in the rise of the Gallé company to prominence in the Paris applied arts market. Émile Gallé’s message states that, by the time of his writing, he already had a “small vase” inscribed with a Gospel quote from Saint John: “Personne n’a un plus grand amour que de donner sa vie pour ses amis”. Here lies the key to confirming the dead’s identity. Unfortunately, the vase’s whereabouts are unknown at this time: it does not appear in F. Le Tacon’s extensive repertory6 of verreries parlantes nor in any other catalogue I am aware of. Such a vase was not included in the important auction sale of the Daigueperce estate, organised by Arcole at Drouot Richelieu, on the 2nd June 19897. Given its historical importance, the vase may well have remained in the family8. While its discovery would be quite interesting to confirm the quote and its recipient, it turns out to be superfluous: for the same Saint John’s verse does appear in one of Émile Gallé’s writings, his eulogy for Marcelin Daigueperce’s funeral, thus confirming our hypothesis and helping to explain the text’s symbolic meaning:

Notre ami [Daigueperce] n’a-t-il pas donné plus de la moitié de son existence parmi nous? (…) Or, l’Évangile nous dit que « personne n’a un plus grand amour que de donner sa vie pour ses amis ».9

Marcelin Daigueperce’s funeral oration by Émile Gallé

Émile Gallé’s funerary speech was published in the April 15, 1896, issue of La Céramique & la Verrerie, Journal officiel de la chambre syndicale, the official publication for the glass and ceramic industry’s union, as part of the organisation’s tribute to one of its leading members. The union’s president, E. Monniot10, first wrote a necrology11, recalling how Marcelin Daigueperce had been one of the syndicate’s founding members after the 1870 French-Prussian war, 23 years earlier, and one of its most active participants ever since. Daigueperce’s death had not been unexpected news, since, despite being only 52, he had been severely ill for some time, having to lay down on February 3rd, 1896, and not rising since. He died in agony, from a cancer of the throat12, less than two months later, on March 29, in his home above the Gallé depot, and he was laid to rest on April 1st, on the eve of the union’s meeting where Monniot read his death notice. Émile Gallé made the special trip to attend the funeral ceremony and read his speech, perhaps at the Saint-Ouen cemetery where the Daigueperce’s grave is located, in one of Paris northern suburbs.

Émile Gallé’s eulogy of Daigueperce was very much appreciated by the assistance, as Monniot (himself quite a devout man13) testified in his account of the ceremony14:

[Émile Gallé] est venu exprimer dans un magnifique langage, avec une émotion pénétrante et communicative, sur la tombe de son fidèle collaborateur, le tribut d’éloges et de regrets qu’il lui devait.

As funeral eulogies go, and despite its sizeable length, this one is strikingly uninformative on Marcelin Daigueperce’s life and career, which is quite a disappointment for the historian. The speech is more a testimony of Émile Gallé’s ambition as a writer than an account of his relationship with Marcelin Daigueperce. It almost reads like a sermon, extolling the departed’s character and moral qualities in religious terms, with heavy christian overtones, culminating in the verse from the Scriptures, “Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends” (Saint John, xv, 13). The selection of this verse from Jesus Christ’s Farewell Discourse looks especially appropriate, given the funerary theme. Gallé’s speech is a last farewell, literally an Adieu (à Dieu) from a Christian perspective:

(…) il est bien permis de dire au revoir, c’est-à-dire rendez-vous à Dieu (…) A Dieu donc, mon brave Daigueperce, camarade dans des combats pacifiques mais meurtriers, ami dans les jours difficiles et beaux, âme énergique, martiale, fière, désintéressée, généreuse, violente à servir les autres, stoïque dans la souffrance ; à Dieu, homme fidèle à sa parole et à ses affections.15

The quote fits not only the occasion but also the date of the burial: Marcelin Daigueperce was buried on Wednesday, April 1st, 1896, in the middle of the Holy Week, on the eve of the celebration of the Last Supper where Jesus Christ gave the speech recounted in Saint John’s Gospel. The liturgical calendar may therefore have played a part in Émile Gallé’s choice of the verse, consciously or not.

The portrait Gallé is making of Daigueperce is one of a fierce defender of the applied arts and of the artists, an unselfish, hard working detail-oriented businessman, with a genuine passion for the objects of his trade – a trait that was carried on by his son and explains the fabled personal collection they were able to acquire. But that’s about it. Émile Gallé alludes to a few personal episodes showcasing Daigueperce’s sense of justice and charity, but in vague terms that preclude any understanding by anyone but his family and close friends.

The lone fact Gallé is confirming is that, in a way, it was Daigueperce that recruited him and not the other way around:

[Marcelin Daigueperce] bataillait pour que l’invention restât la récompense de l’inventeur que l’artiste eut un peu de sécurité, qu’il fut encouragé, réchauffé par un peu d’affectueuse estime. Et il payait d’exemple en défendant le drapeau qu’il s’était choisi, le dépôt dont il avait demandé la garde. Et dans sa bouche ce terme, dont nos fabricants désignent leur magasin de vente, reprenait toute la signification noble : « le dépôt, votre dépôt! »16

Marcelin Daigueperce was born on the 23rd June 1843, in Limoges, the son of Léonard Daigueperce, a painter on porcelain. Rather than following his father’s footsteps in the industry, he became a sales representative for various earthenware and china manufacturers, and moved to Paris. Impressed by the quality of the Gallé company’s ceramic productions, he contacted one of their main manufacturers at the time, the Faïencerie in Raon-l’Étape, in the Vosges, whose director, Adelphe Muller, put him in contact with Gallé. Marcelin Daigueperce then convinced Émile Gallé to let him run his depot in Paris and made it the commercial flagship of the company, establishing himself in the process as an indispensable advisor.

Was the Daigueperce vase a vase de tristesse?

The vase alluded to in the visiting card’s message is therefore adorned with a quote that was, in a way, public-tested in the eulogy, and one that evidently met Daigueperce’s widow approval. For, while it is certainly not the most consequential detail, one must note that, according to Émile Gallé’s message to Adolphine Daigueperce, the funerary vase was finished at the time of his writing, since he already had the verse engraved onto it. The vase was therefore not the object of his yet unfulfilled promise to Marcelin’s Daigueperce’s widow, and it did not pertain to the task he set himself to for the following night. Besides, as it is well-known, Émile Gallé was not working himself on his creations but directing the many craftsmen in charge of their making. The card’s message was about something else. The most plausible guess would be that Adolphine Daigueperce had requested a copy of Émile Gallé’s speech, perhaps right after its delivery at the funeral. Unable to give her his notes, if only because they would have been barely legible, but also because he would have needed them for their incoming publication, Gallé would have promised to send her a copy. It looks like his card was the answer to a reminder of his promise to her, asking for the quote he had used in the eulogy. In this quick reply, he was thus reassuring her he had not forgotten, telling her the verse in question had already been inscribed on a vase he had had prepared for her and announcing he would work on his copy of the speech the same evening. This sequence of events means that the card could be dated from the days or weeks following the burial, perhaps from late April 1896.

The delay’s length between the funeral and the message has some consequence in determining the kind of vase he could have selected. With only a few days to spare, and perhaps even with more time in hand, he would have simply chosen a finished object in his inventory, deemed of sufficient value and proper decor, and had the Gospel quote engraved – the way Henriette Gallé did ten years later for the Keller’s son, for instance. Only if he had more time, could he have ordered a special vase to be made.

One can only venture what kind of vase Émile Gallé selected or had made for Marcelin Daigueperce. One logical choice would have been one of his vases de tristesse, the black hyalite cameo glass series he created for the Exposition universelle in Paris in 1889 and that he reprised, with various decors, during the 1890s up to the 1900 Exposition and later. The dark material was a proper conduit for the melancholy and sadness experienced after the disappearance of a loved one, or, as it’s been suggested, in line with many of Gallé’s creations in 1889, after the loss of the Alsace and Lorraine provinces: several thistles-themed vases figure among the most famous of these vases de tristesse, dedicated to the remembrance of the 1871 Annexation.

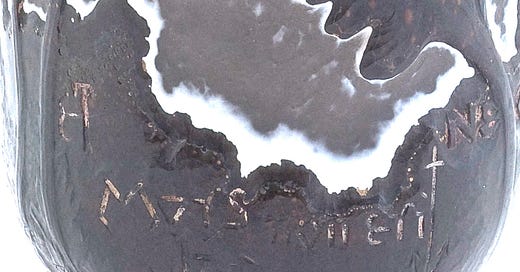

Émile Gallé made many variations of these, but one in particular looks relevant to the Daigueperce case, since it is yet another verrerie parlante with a saint John’s quote and a firmly established date, the Neque dolor erit ultra glass piece from 1894. This small glass goblet with a simple decor of black poppies, carved over a white and translucent background, was part of Gallé’s offering to the Salon de la Société nationale des Beaux-arts in 189417, where it was bought by the Paris municipality18. The goblet bears a long Latin quote from saint John’s Book of Revelation (xxi, 4), carved both in cameo and intaglio, beginning on the lower part of the body (Et mors non erit ultra / Neque luctus / Neque clamor / Apocal. XXI) and continuing under the base (Neque dolor erit ultra via prima abierunt / Apocal. XXI) next to the signature:

And God will wipe away every tear from their eyes; there shall be no more death, nor sorrow, nor crying. There shall be no more pain, for the former things have passed away (New King James translation)

The messianic message of hope and consolation fits perfectly with a funerary theme, in a somewhat similar way to the saint John’s Gospel quote discussed here. Daigueperce’s vase might well have been a closely related artwork. It does not mean, however, that there aren’t many other alternatives. In Émile Gallé’s speech, the quote comes as the conclusion of a development praising Marcelin Daigueperce’s generosity and charity. Gallé implicitly compares him to Saint Martin cutting his coat in half for of a beggar. While a realistic depiction of this famous hagiographical episode in a Gallé work of art looks quite implausible, to say the least, one can envision other symbolical pictures on similar themes. One well-known Christian symbol for sacrifice and paternal love, for instance, is the pelican tearing itself apart to feed his blood to his little ones: Émile Gallé did use the heraldic version of this theme on some enamelled glass pieces in the 1880s, like the À cœur aimant tout possible vase in the Orsay Museum19. He may have used a comparable theme on the vase he gifted to the Daigueperce family.

To sum up, the visiting card sent by Émile Gallé to Adolphine Daigueperce bears testimony to the genuine sense of loss he experienced at the death of his collaborator and friend, Marcelin Daigueperce, on the 29th March 1896. The message references what probably was a vase de tristesse, a gift from Émile Gallé as a funerary homage. The vase was engraved with a quote from the Farewell Discourse in saint John’s Gospel, a text Émile Gallé had used in his eulogy of his friend, spurred by the occasion and perhaps by the liturgical calendar too, since Daigueperce’s burial took place on Holy Wednesday, on the 1896 Easter week. The misunderstanding of the card by the auctioneer came in part from its separation from the bulk of the Daigueperce’s archives. The lack of context makes it all the more difficult to analyse, unless it can be cross-referenced with some external document, as it is fortunately the case here with the articles from the La Céramique & la Verrerie journal. That’s why, in general, the dispersal of such documents in auctions like this is, in the end, so damaging.

© Samuel Provost, 24 September 2023.

Bibliography

• Charpentier F.-T. and Thiébaut P. 1985, Gallé : Paris, Musée du Luxembourg, 29 novembre-2 février 1986, Paris, Réunion des musées nationaux.

• Le Tacon F. 1998, L’œuvre de verre d’Émile Gallé, Paris, Éd. Messene.

• Le Tacon F. 2010, Émile Gallé, L’amour de l’art, les écrits artistiques du maître de l’Art Nouveau, Place Stanislas éditions.

• Thiébaut Ph. 2004, Émile Gallé, le magicien du verre, Paris, Gallimard.

Notes

“Excuse me, dear Madame Daigueperce, today has been so hectic in various ways that I have not been able to fulfil my promise, but I will work on it this evening. Here is the text I quoted and inscribed on our late friend's little vase: "No one has greater love than this, to lay down one's life for one's friends" St John, xv. We are thinking of you at this painful time. What a void!”

The letter sealing this agreement is preserved in the Orsay Museum. See the transcription in Thiébaut 2004, p. 110.

Thiébaut 2004, p. 39.

Civil registry for marriages, Ville de Paris, 10e arrondissement, May, 9, 1868, nr 504.

Civil registry for marriages, Ville de Paris, 10e arrondissement, May, 21, 1904, nr 1022.

Le Tacon 1998, p. 200-213.

Exceptionnel ensemble de 200 œuvres de Émile Gallé provenant de la collection d’un de ses collaborateurs et à divers, vente Arcole, Félix Marcilhac et Jean-Marc Maury experts, 2 juin 1989, Drouot Richelieu, Paris.

It seems doubtful it could have been used as a funerary urn, as the auctioneer suggests. A cinerary urn looks out of the question: for once, cremation was only made legal in 1887 in France and remained anecdotal well into the 20th century (see Jacqueline Lalouette, “La crémation en France (1794-2014). Des sources multiples et diversifiées”, in Bruno Bertherat (ed.), Les sources du funéraire en France à l’époque contemporaine, Presses Universitaires d’Avignon, 2015, p. 83-99). In the 1890s, the only crematorium available was in the Père Lachaise cemetery, while Marcelin Daigueperce was buried in the Saint-Ouen one. The cemetery registry mentions that the remains were exhumed and relocated on the 6 May, 1896, a month after the funeral, presumably because the Daigueperce widow had bought a new funerary monument. Would she have placed Émile Gallé’s precious gift inside her husband’s tomb rather than keeping it for herself as a keepsake?

“Paroles prononcées aux obsèques de M. Marcelin Daigueperce par M. Émile Gallé, de Nancy” in La Céramique & la Verrerie, Journal officiel de la chambre syndicale, 15e année, 1st-15 April, 1895, p. 30-31.

E. Monniot was the owner of a small business in glass lighting fixtures, with a store on Martel street in Paris, and workshops in Saint-Ouen (mentioned in P.-J. Derainne, Le Vieux Saint-Ouen, Mairie de Saint-Ouen, Archives municipales, undated, p. 21). Monniot was only decorating glass and making lamps, buying his blanks from the Clichy glassworks: see an interesting testimony from April 1878 about this in G. Aubin, Y. Lamonde (ed.), Louis-Antoine Dessaulles, Paris illuminé : le sombre exil. Lettres 1878-1895, Presses de l’université de Laval, 2019, p. 31. For the Monniot label, see Hartmann, Glasmarken-Lexikon p. 720 and nr 10824.

“Nécrologie. Marcelin Daigueperce”, in La Céramique & la Verrerie, Journal officiel de la chambre syndicale, 15e année, 1st-15 April, 1895, p. 29-30.

Thiébaut 2004, p. 39.

Louis-Antoine Dessaules went so far as writing that Monniot was spending more time in church than attending to his business: G. Aubin, Y. Lamonde (ed.), Louis-Antoine Dessaulles, Paris illuminé : le sombre exil. Lettres 1878-1895, Presses de l’université de Laval, 2019, p. 31.

“Nécrologie. Marcelin Daigueperce”, in La Céramique & la Verrerie, Journal officiel de la chambre syndicale, 15e année, 1st-15 April, 1895, p. 29.

“It is quite permissible to say goodbye, in other words, to God (...) To God then, my brave Daigueperce, comrade in peaceful but deadly battles, friend in difficult but beautiful days, energetic soul, martial, proud, disinterested, generous, violent in serving others, stoic in suffering; to God, a man faithful to his word and his affections.” Ibidem.

Ibidem.

It was also part of the small exhibition Pour l’Art in Bruxelles the same year, the second exhibition of the Cercle de la Libre Esthétique: Le Tacon 2010, p. 283.

Orsay Museum inv. OAO 528. For a detailed commentary on the piece, see Gallé 1986, cat. 83, p. 168-169.

How to cite this article : Samuel Provost, “A posthumous homage from Émile Gallé to Marcelin Daigueperce”, Newsletter on Art Nouveau Craftwork & Industry, no 25, 26 September 2023 [link].