Fake Gallés (I): When a floral design masquerades as an undersea landscape.

Or how to ruin an authentic Gallé vase.

Or how to ruin an authentic Gallé vase.

The most common question a Gallé expert is being asked is to assess the authenticity of a glass piece. Given the sheer quantity of Gallé copies, that’s a fair question. More often than not, the answer is easy enough, even when judging from pictures alone. I have meant from some time to tackle this basic issue in this newsletter, but it seemed a bit trivial, boring even, when so many guides and websites already exist, often by more competent experts on the subject: see for instance Tiny Esveld’s Glass made transparent, where fake Gallé glass makes up a fair share of the various malpractices and counterfeits the author examined. But the questions keep coming, and, given that the practical perspective on Gallé is one of those the newsletter strives to keep, it seems logical to address this question as well. This article is therefore the first of a series aimed at uncovering some fake Gallés as well as providing a bit of context, when possible, on the Gallé forgeries.

By “fake”, one usually refers to two different general types of forgeries:

first, the out and out counterfeits, i.e. glass pieces that bear an imitation of the Gallé signature but have nothing to do with the company (whether they are “apocryphal Gallés”, i.e. “rebaptized” original pieces from another glassmaker, such as Nicolas, De Vez, Burgun & Schverer, etc., or newly made pieces with the express purpose of imitating Gallé ones, the Rumanian and Chinese cheap copies for instance);

and second, genuine Gallé pieces that have been touched up to some varying degree, thereby ceasing to be considered as Gallé original artwork, usually to conceal some damage or even to recycle a broken piece, but also sometimes in a misguided attempt to enhance their value.

This article will focus on an example of this latter category, which surfaced last month in the French Art Glass Facebook groupand was met with equal enthusiasm and scepticism. At first glance, something was definitely wrong with this Gallé vase, in my opinion, but it also featured numerous details that were right, and so it took a closer look to uncover what must have transpired.

Disclaimer: this analysis is provided as an academic study in the history of applied arts and not as a professional expert’s report.

On a Gallé industrial series with an “hybrid” decor.

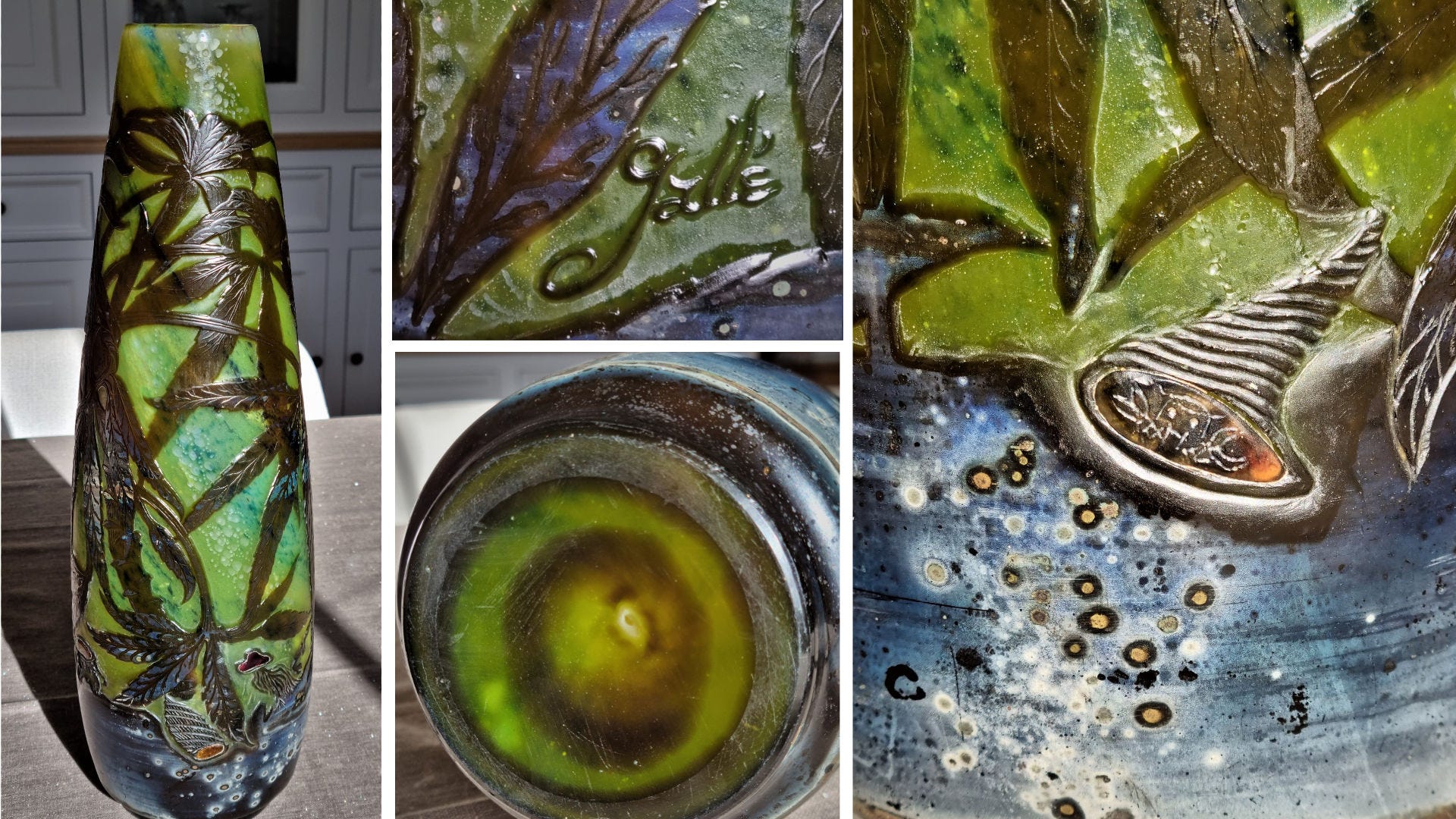

The vase is mould blown (in the original sense, not in the relief series one), in the shape of a truncated shell resting on a small, slightly recessed heel. The form is well attested throughout the Établissements Gallé’s period of operation, particularly after the death of Emile Gallé, up to the 1920s included. The inner layer is a transparent amber opal/olive glass, with intercalated inclusions of platinum (?) and bluish dirt arranged in a swirling band, beneath a brown, acid-etched outer layer of a foliate pattern. The finish is a metallic (silver salt) precipitate, mostly accentuated on the lower part near the base. This type of precipitate can be found on vases from the 1890s-1900’s as well as after the First World War.

The main decoration is an acid-etched ascending floral motif (from the base to the neck). It depicts the stems and leaves of a land plant, almost certainly Fetid Helleborus (Helleborus foetidus), with no visible flowering. The secondary wheel-graved decoration consists of several marine creatures, two crustaceans (crab, hermit crab), two jellyfishes and a seahorse, all of small size and almost all located in the lower part of the vase, near the bottom. Each of these creatures is enhanced by a piece of wheel-carved applied glass of bright colour (red for the fin of the seahorse, dark red for the body of the jellyfish, bright orange for the hermit crab and for the crab. The seascape is completed by wheel-engraved trails of air bubbles from top to bottom over the entire height of the vase, following a line parallel or superimposed on the bluish oxide inclusions. The result is a convincing suggestion, on first analysis, of a seascape that is analogous, in its compositional principles, to many of Emile Gallé's works from the late 1890s to 1904, and then under his successors up to and including the 1920s (with different techniques for the latter period).

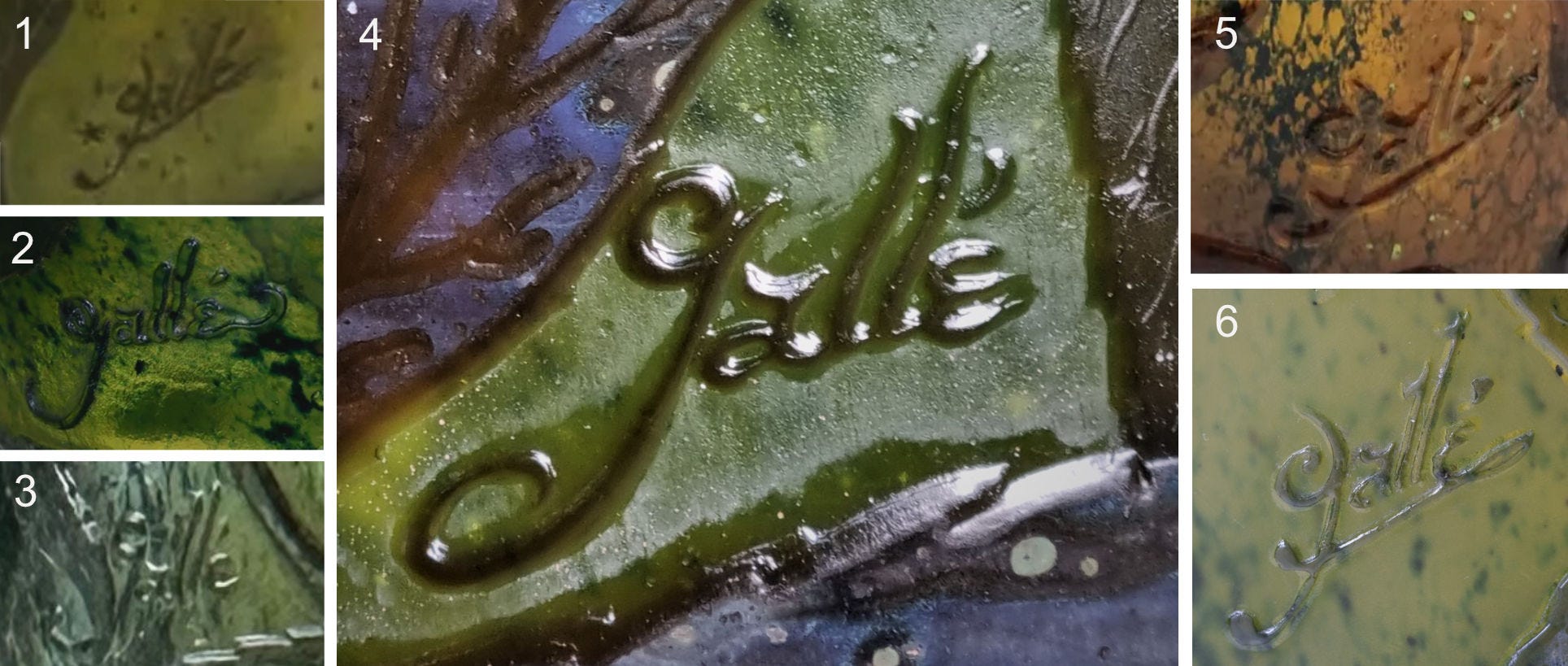

The vase is signed with the simple name Gallé, acid-etched in cameo, in the brown outer layer, with a spelling that corresponds, in my typology of the Établissements Gallé signatures, to a variation of the Mk IV type, with an accented epsilon -έ final and not a Latin -é. This signature is attested both around 1900-1904 and afterwards, but much more rarely.

A provisional conclusion would therefore be that this is a high-end industrial series, due to the combination of acid etching on a rather basic shape with the presence of appliqués and a reworking of part of the decoration. Although most of the technical characteristics can be found, to varying degrees, on productions from Emile Gallé's last fifteen years as well as on pieces from the 1920s, a dating of around 1900-1904 would, at this stage of the analysis, be the most likely.

Two stark oddities, however, lead us to suspend judgment and call for further investigation: the combination of a terrestrial botanical species with a marine decoration, and the very naive, even clumsy or childish, rendering of the marine creatures.

The Fetid Hellebore series with intercalated inclusions and metallic lustre.

The first point is the identification of the plant species that constitutes the main decoration of the vase: which plant is it?

To my knowledge, this precise decoration is not documented in the various graphic collections of the Établissements Gallé, nor in the notes of Émile Gallé. The identification and authentication of the decoration can only come, therefore, from the comparison with other specimens of the same series, or very close ones, by their technique and/or their decoration.

The series is rare, but two museums at least do possess a specimen, the Kitazawa Museum in Japan, a flask or bottle shape with a long, narrow, flared neck (dated ca. 1900), and the Glasmuseum Hentrich in Düsseldorf’s Kunstpalast (inv. Mk P 1970-228), an amphora shape without handles (dated ca. 1900-1904). To these can be added several vases that have come to auction in the last two decades. The main decoration and technique are identical - it is indeed the same series of acid-etched two-layered glass, brown over amber/light green with metallic inclusions, with a metallic precipitate lustre finish on the lower part and foot (where applicable). As on the example studied here, some of the lower leaves of the plant extend onto the lustre base of the vase (where present) where they are engraved in intaglio rather than cameo. It should be noted that this is a very unusual feature. On “ascending” decorations, the cameo engraving of the main motif may be complemented by intaglio engraving of secondary motifs on the outer layer otherwise left intact on the base or neck, but, to my knowledge, this type of transition or combination between the two methods for the same decorative element is exceptional.

The plant shown is characterised by its leaves, which are arranged horizontally around the stem and are divided into 7 to 11 narrow leaflets with a saw-toothed edge, and by a discreet, even invisible flowering: the characteristic shape of the leaves makes it possible to recognise the Fetid Hellebore (Helleborus Foetidus) or Bear’s foot. This perennial plant, characteristic of forests and scrubland, is common throughout central and southern France, and only flowers twice in its life cycle. The flowers are small, green, bell-shaped and nodding with persistent sepals: neither of the two museum vases has one in its decoration. However, other shapes from the same series, attested in auctions, clearly show these small flowers: this is the case of a baluster or urn shaped vase sold at Christie's on 3 October 2007 (Live auction 7423), a second one by Douglass (KS, USA) on 18 March 2017, or of a small vase sold on 26 February 2021 by Lombrail Teucquam (lot 152, not pictured here), where two flowers, one blooming and the other in bud, are clearly visible.

It is therefore not a seaweed or aquatic plant as one would expect in a vase with an underwater theme, but a land plant. Above all, none of the six vases identified in this series has any additional decorative elements relating to the marine environment, as is the case for the wheel-engraved creatures and air bubble trails on the vase in question. This specificity appears all the more incongruous and cannot be easily explained. It is certainly common in Établissements Gallé’s line for the same industrial series to be made in several versions, according to the degree of quality and sophistication of the decoration, in order to meet several market segments. The most elaborate versions are referred to as semi-rich and rich series, while the last ones involve wheel work, or even applications, or other costly technical variations. But these variations never change the general character of the decoration, contrary to what happens in our case, where the floral decoration of the basic versions of the series would allegedly become a marine background in its most expensive and prestigious iteration. Even if Emile Gallé enjoyed hybridizing decorations, mixing elements from different artistic traditions in original compositions, he never transplanted terrestrial flowers into the middle of the ocean for his numerous marine-inspired works. The very idea would probably have seemed absurd to the renowned botanist that he was, one who had seaweed brought over in barrels from the coasts of Brittany in order to be able to study them and thus better depict them...

Marine fauna elements as added subjects.

The elements of the marine décor must therefore be re-examined, all the more so as they break the harmony of the décor with their sharp, unshaded colours, as well as their naive drawing which borders on the clumsy. There is a great contrast between the meticulous botanical realism of the hellebore and the schematism of the crustaceans, far from the usual rendering they present in Gallé's usual underwater compositions. Some of these are downright cartoonish, like the hermit crab shown on the overview picture above. The nature and treatment of the glass applications are also different from what is usually found on Émile Gallé's creations, even for marine creatures. For example, they can be compared with the octopus dish in the former Gerda Koepff collection, where the acid-etched and wheel-engraved decoration is also supplemented with applications of shells, but also for the eyes of the main subject, to which they are harmoniously matched (see the picture above)1.

Jellyfishes, crabs and seahorses commonly feature on Émile Gallé’s abundant sea-themed artworks as well as on his successors’ series, but in a markedly different likeness, as can attest two specimens shown above, both acid-etched multilayered glass, the first from the former Chua collection, and the second from a 1990 auction sale by Ader Picard Tajan. There are multiple renderings of the marine fauna on Gallé glass, in more realistic or on the contrary more stylized design, but one has never encountered such a sketchy outline as the one in the vase under scrutiny here.

The explanation for this discrepancy becomes apparent when the composition is analysed, particularly the location of these sea creatures: they are all located either along the upper edge of the bottom background or between exaggeratedly spaced leaflets of the hellebore foliage. The clearest cases are those of the lowest jellyfish and the seahorse, both inserted in a gap between two groups of leaflets on the same leaf: it is not difficult to restore one or even two leaflets in this gap, which would give the foliage a more regular structure and appearance. In fact, if we look closely at the end of the stem from which the existing leaflets are detached, we can see the start of a groove similar to the veins of the latter, but which is abruptly interrupted. It can be assumed that these are the last traces of additional leaflets that have been stripped off to make room for the seahorse and the jellyfish (see an attempted reconstruction below).

The surface of the glass around the two subjects also seems to have been reworked and repolished. The same can be said for the other creatures, with the difference that those closest to the base have been cut into the plain layer of the base rather than the foliage of the hellebore. Other elements point in the same direction: the remaining leaves near the applied elements have sometimes had to be retouched and have, for example, had their serrated edges damaged or even erased, as is the case for the leaf to the left of the crab. Finally, the bubble trails in a martelé-like fashion are questionable, because this motif is not used, at least with this technique, on Gallé's marine decorations. More decisively, this work was clearly done after the fire-polishing finish that characterises the vase, since it’s punching through it.

The incongruous nature of the marine décor elements, both in their association with a terrestrial plant and in their clumsy execution, is thus explained by the fact that they do not belong to the original design.

Hypothesis on a make-up.

The identity and motives of the glass engraver responsible for the extensive transformation of the vase’s decoration remain to be examined. The most plausible explanation is that the aim was to increase the commercial value of the object, either because it was diminished by a defect or because a more technically and artistically complex decoration was considered more desirable: wheel-carved works are recognised as superior ones and routinely fetch far higher prices on the art market. This is even truer of glass with applied parts of course.

The second explanation must be discarded, however, in our opinion, unless one assumes extreme naivety combined with technical incompetence on the part of the author of the alterations. The first explanation, on the other hand, corresponds to proven practices, even at the time of the Établissements Gallé and even more so at the end of the last century as well as very recently. Examples abound of vases that had a manufacturing defect (burst bubble, trace of the mould, burr of the acid etching, etc.) or that had suffered more or less serious damage from their use, and that were touched up in order to mask these defects. It is known that during the First World War, unable to renew its stock of glass blanks due to the stoppage of the main fusion furnace, the management of the Établissements Gallé did not hesitate to engage in such dubious practices: it made the small team of decorators it continued to employ work to make up second or third choice pieces, which had been previously relegated to the factory attics because they were unfit for sale2.

The absurdity of this hybrid decor of an underwater fetid hellebore, as well as the approximate technique used, allow us to eliminate this hypothesis. The author of the modifications is neither a Gallé worker nor a contemporary of the vase: the work must be much more recent and date, perhaps, from the end of the 20th century. At that time, an unprecedented commercial craze for Gallé glassware, combined with a general lack of knowledge outside the smallest circle of specialists, justified for all kinds of infringements of ethics, from the simple repolishing of a chipped rim to complete forgery. The type of radical make-up shown in the present vase is obviously regrettable, as the underlying original is a relatively rare piece of excellent workmanship.3 It is likely that it was justified in the eyes of its maker by the presence of at least one flaw, almost certainly where one of the coloured glass pieces was clumsily applied. With a certain ingenuity but also great naivety, he must have decided to transform the whole decoration and to multiply the marine elements to give the vase a very superficial coherence. Other scenarios are of course possible, but all presuppose an intervention outside the Gallé factory and after the vase was made.

The date of the original vase.

The date of the original vase remains uncertain, as the hellebore motif is associated with a double-layered glass and intercalary dirt of slightly different colour and rendering. It is therefore unclear whether these are simple variations within a single general series, or whether they are several series that take up the same theme with a potentially significant chronological shift.

The specimens used in our demonstration thus already possess an obvious difference in finish: the metallic precipitate lustre seems to be absent from several vases. The nature and importance of the intercalary oxides also varies. An interesting specimen in this respect, also original in form, belonged to the Thomas Chua Collection, dispersed in 20224. In this case, the vase has a naturalistic form imitating that of the hellebore flower, which hints at an earlier rather than a later date.

A clue lies in the variety of signatures used : they are simple “Gallé” ones, always on the body, never under the base, variants from the Mk I to the Mk IV types. The specimen sold by Rossini, in 2021, had a Mk II signature, the Gallé-with-star type from 1905 to 1908. This could point to a series made in a transitory stage of the signature system in use by the Établissements Gallé, either in 1904-1905 or in 1908-1909. Additional data would be needed to confirm this hypothesis, but there are other series from this period showcasing the same techniques, be it the use of intercalary oxydes or the metallic precipitate on the surface.

All these signatures are cameo engraved too, which in itself is a confirmation of a sort that, on the vase in question, all wheel-carved or applied features represent some secondary work from a forger: on technical superior glasswork, Émile Gallé usually had the signature engraved intaglio, it seems, rather than in cameo, in a wavy hand-script or otherwise elaborated style rather than the plain signature this specimen features.

© Samuel Provost, 9 April 2023.

Footnotes

Ph. Thiébaut, Gallé, le testament artistique, Hazan, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, 2004, fig. 12, p. 52 for a close-up. The catalogue has a wide array of sea-themed vase which provide a useful comparison for the matter at hand.

S. Provost, « Une cristallerie d’art sous la menace du feu : les Établissements Gallé de 1914 à 1919 », in Thomas C. et Palaude S. (dir.), Composer avec l’ennemi en 14-18. La poursuite de l’activité industrielle en zones de guerre. Actes du colloque européen, Charleroi, 26-27 octobre 2017, Bruxelles, Académie royale de Belgique, p. 105‑118.

As Mike Moir astutely noted in our discussion of this piece, the thin web of scratches on the base are a reliable sign of age and therefore of the authenticity of the piece.

Doyle Sale 22FD03, 2 March 2022, lot 89.

Bibliography

Kiyoshi Suzuki, Glass of Art Nouveau, Mitsumura Suiko Shoin, 1994 (in Japanese).

Hilschenz-Mlynek H. and Ricke H. 1985, Glas: Historismus, Jugendstil, Art Déco, Band 1, Frankreich. Die Sammlung Hentrich im Kunstmuseum Düsseldorf, Munich, Prestel-Verlag.

Thiébaut Ph., Gallé, le testament artistique, Hazan, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, 2004.

How to cite this article : Samuel Provost, “Fake Gallés (I): When a floral design masquerades as an undersea landscape”, Newsletter on Art Nouveau Craftwork & Industry, no 21, 9 April 2023 [link].

Fakes are a big nuisance and disappointment, but a fascinating subject of research as well. They can be highly instructive - especially, if they are being revealed so masterfully as in this case. Would I myself have become suspicious with this vase? I'm afraid not...