Georges Ferry (1881-1948) and his short-lived Verrerie d’art Ferry in Nancy.

The unrealised ambitions of a little known Gallé alumnus.

The recent sale, by the Quittenbaum auction house1, of a landscape-themed vase bearing a “G. Ferry / Nancy” signature prompted the following investigation of this almost unknown glassworker in Nancy.

A little known painter decorator in Nancy.

Information is scarce about Georges Ferry, all the more because both his first and last names are very common ones in the early 20th c. For instance, the Nancy directory from 1922 lists no less than 77 homonyms and none of them can be easily identified with Georges Ferry, the painter. He is notably absent from general dictionaries of artists, like the Benezit, as well as from more specialised literature, like Hartmann’s lexicon or Olland’s dictionary, to name only the usually most serviceable ones. The following account relies heavily on public archives that provide scant information and leave many blanks.

His birth certificate outlines the basic facts of his life: Georges Eugène Ferry was born in Nancy on the 1st January 1881, the son of Jean Baptiste Ferry, a 35 years old file cutter (tailleur de limes) and Anne Marie Demezy, 27 years old. He had four brothers and two sisters, none of them in the same trade. The family lived on the Strasbourg street (no 232), until at least 1901, and probably until the father’s death in 1905. Georges Ferry married, soon after, one Pauline Signart on the 23rd Octobre 1908, and they moved in an apartment on the Tapis vert street (10 bis). They had a son, born in 1909, also named Georges, and then a daughter, Yvonne, born in 1914.

Georges Ferry most likely began the career of a painter on glass as an apprentice for Daum: at 15, he was already listed as a décorateur on the 1896 census2, and then at 21 as a peintre verrier for Daum, in 1901. According to Christophe Bardin3, the Daum brothers created their own drawing and modelling school ca. 1894-1897, shortly after their two most prominent creators joined the company, Jacques Gruber in 1893 and Henri Bergé in 1895. They were concurrently teaching drawing, in the École des Beaux-Arts de Nancy and in the École professionnelle. It looks like the young Georges Ferry was one of their first students in the Daum in-house drawing school4.

In 1901, at the age of 20, Georges Ferry should have been enrolled for his military service, but he was granted an exemption on the ground of being a worker in the art industry (“ouvrier d’art”)5: his listed profession on the military register is then painter decorator. We lose track of him afterwards until the 1911 census, when his stated profession is a painter, that is still of course a painter-decorator on glass, but for Gallé this time. He therefore represents a case of transfer from Daum to Gallé, that was quite rare considering the rather cool relationship between the two glasswork powerhouses in Nancy.

The exact date of this unusual switch is unknown6, during the 1901-1911 decade. But it’s worth noting that one of his brothers-in-law, Ernest Courouve7, two years his senior, was a painter in the Gallé factory and one can surmise that he might have played a part in Georges’ transfer from Daum to Gallé. Ferry then stayed in the Établissements Gallé’s employment at least until 1914, when he was part of the JEFFER project, the failed secession project from Gallé that was led by Jean Rouppert (see below).

After the war, nothing much is known about him, since he and his family moved again, presumably still in Nancy or its immediate surroundings because, by 1926, they had taken up residence in a building on the avenue de Boufflers (n. 29), practically across the street from his brother-in-law’s house. At this time, he was his own boss, having founded a small glass art studio located on a nearby alley, impasse Saint-Lambert, just a few hundred meters down the hill from his home.

What happened to him in the 1930s and 1940s is still unknown. His birth certificate mentions that he remarried in Marseilles on the 19th June 1948 (he was then 67 years old) with Julie Jeanne Samat, and died in Salon-de-Provence a few months later, on the 26th November. This crucial piece of information can explain both some Provence life-themed creations, like the vase with an olives picking scene (hardly a scene from Lorraine!), and the fact that some of his seemingly late-life painted ceramics reappeared in an auction in Salon-de-Provence8 and more generally in antiques stores in the area (see below). When and why did he move to Southern France remains at this point an open question. One can only speculate that he was part of the many refugees who left Lorraine after the Fall of France in 1940 and resettled in the Free Zone. Provence, in particular, was a haven for many artists in this period.

Georges Ferry, Jean Rouppert, and the JEFFER project.

Most of the available biographical information comes from the private archives of Jean Rouppert, the Gallé painter and designer. From late 1913 to 1914, Jean Rouppert’s letters to his future wife, Madeleine Labouré, contain some precious details about his tentative partnership with Georges Ferry9. Recruited in early August 1913, Jean Rouppert was already entertaining ideas of working by himself three weeks later10. By the next February, he and three other Gallé workers, Georges Ferry, Marie Henri Jeandidier (1893-1914)11 and Hubert Roiseux (1884-1918), had agreed on creating their own art glass company, under the pseudonym JEFFER:12

Dimanche après-midi, nous avons eu réunion chez l’un de mes futurs associés. Nous sommes quatre maintenant. Nous allons former une Société sous la signature commune : Jeffer. L’un est chargé de la partie représentative et commerciale. Le second de la partie gravure et verrerie. Le troisième, en collaboration avec moi, de la partie artistique et décorative. Il fera le le paysage et le vitrail, moi je reste seul chargé de tout ce qui sera figures et personnages (…) Avec ce système, le pseudonyme Jeffer nous couvre et nous permet d’attendre tout en conservant notre place chez Gallé.13

The names of the four co-conspirators appear in another letter from Rouppert, the most explicit one on Georges Ferry’s character and his role in the future company:14

C’est moi qui ai établi les statuts ; ils sont formels. Quiconque se déroberait à ses devoirs perdrait tout profit et serait immédiatement exécuté [sic]. D’autre part, il n’y a que deux créateurs sur nous quatre. R[oiseux], celui dont je te parlais, est un excellent ouvrier, mais ouvrier seulement. Il sait graver à la roue, connaît la verrerie et un peu la chimie. J[eandidier], bon décorateur aussi, connaît la porcelaine, la céramique, les émaux et terres cuites. D’artistes créateurs il n’y a que F[erry] et moi. J[eandidier] et R[oiseux] sont donc sous notre dépendance, ils ne peuvent rien tenter sans nous qui sommes la tête.

En F[erry], j’ai toute confiance. Il s’est fait bâtir une maison à crédit. Or, terrain et maison ne sont pas payés (environ 18.000 francs) et ses économies sont minces. Celui-là veut aboutir parce que la nécessité le pousse.

Ensuite, il est très fort pour l’agencement décoratif et le vitrail, il fait de délicats paysages et des fleurs, mais il est médiocre en personnages et physionomies. Tout ce qu’il fait, je peux le faire et même ce qu’il ne fait pas (…)

Il est vrai que la question pratique, je suis le moins habile étant nouveau venu dans le métier.15

According to Rouppert, Georges Ferry was apparently eager to emancipate from the Etablissements Gallé to earn a better living because he was having his house built in Nancy, a rarity among the Gallé workers, and he was deep in debt as a result. A Nancy periodical, L’Immeuble et la construction dans l’Est, registered all applications from new buildings in Nancy. Several appear with the name of Ferry in 1911-1913 which must be the period when he undertook this endeavour. The difficulty lies in identifying the right one. It might be the application for a house located on 64 Avenue de Boufflers, because in 1926-1931, his mother, Anne Marie (b. in 1854, widowed in 1905) is registered as living with her daughter and her son-in-law, the architect Victor Berg, on 66 Avenue de Boufflers (and there is no street number 64 at either date – so there might have been a change in the street numbering)16. Moreover, it would be worth finding out if Berg is the architect of the house that could then have been a family project. By 1926, however, as it’s been already noted, the Georges Ferry family was back living in an apartment block on 29 Avenue de Boufflers (their last known address), a fact that suggests they had forfeited their house, if it ever was completed.

As for the JEFFER project, we only have Rouppert’s testimony about it, in flirting letters where he was obviously trying to impress his soon-to be wife with the account of his quick rise among the skilled workers of the Gallé factory. His tale cannot therefore be taken at its face value, and a critical reading is warranted.

The JEFFER moniker provides a clue, perhaps, about the budding association’s original founders. In Rouppert’s telling, the name is supposed to be composed from all four partners’ abbreviated family names (Jeandidier, Ferry, Roiseux, Rouppert), but in reality, it’s hard not to wonder if it would not be more easily explained as the concatenation of the first two only, as in JE(andidier)FER(ry) with an additional “F” that could be explained away by spelling or phonetic concerns. That could be why, on the other hand, it contains only one ’R’ while it is the initial letter of two associates, Rouppert and Roiseux. And in that case, it means that, probably, Jean Rouppert and Hubert Roiseux aggregated themselves to an existing project, led by Jeandidier and Ferry. Despite his telling of the events, there’s a case to be made that Jean Rouppert might not have been the initiator of the JEFFER project.

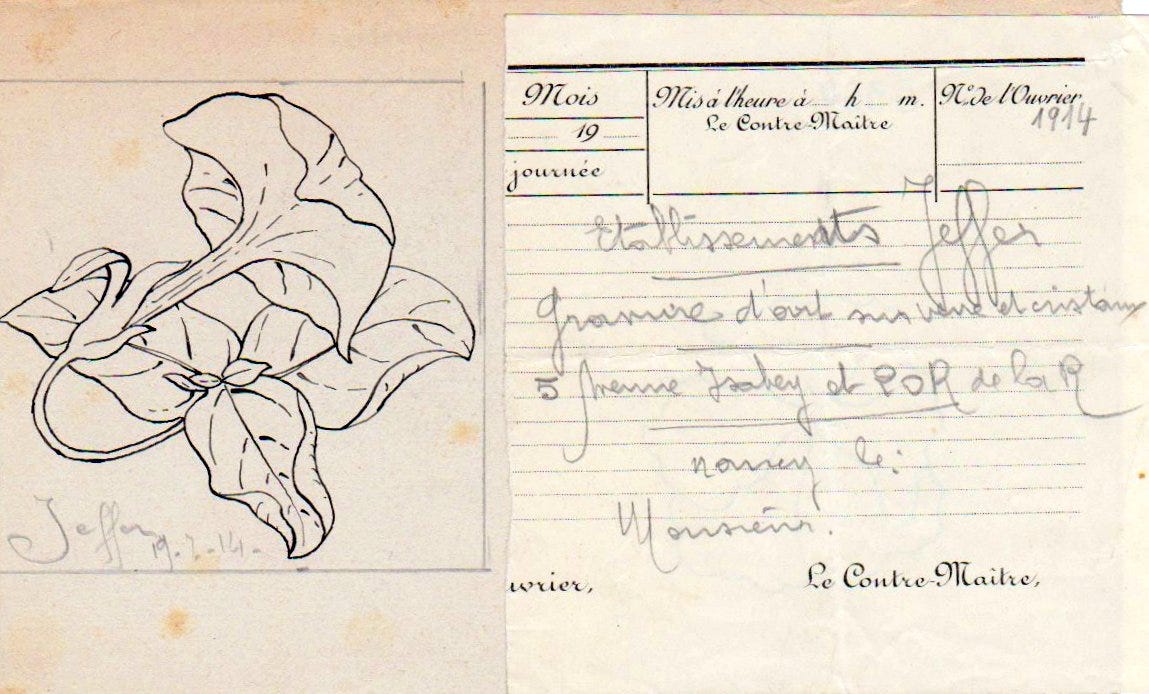

On the other hand, one of the rare documents preserved on the matter looks like a letterhead project for the “Etablissements Jeffer” (see above), with a signed and dated flower sketch, the company name and its activity (“gravure d’art sur verre et cristaux”), as well as two street addresses in Nancy, that happen to be Roiseux’s (5 avenue Isabey) and Rouppert’s (20 rue de la République). The date, 19 February 1914, falls squarely between the two Rouppert letters quoted above. This document does suggest that Rouppert and Roiseux were somehow leading the project, since it lists their home addresses and not those of Jeandidier and Ferry.

But this does not preclude the existence of a previous collaboration between Ferry and Jeandidier. This hypothesis finds, in fact, some strength in the existence of a vase signed by both (see below): it may represent an early attempt at a collaboration. Given Jeandidier’s youth and his early death in 1914, that vase can be safely ascribed to a 1913-1914 timeframe. This argument is not iron proof, since, in the case of the Société des graveurs réunis for instance, it happened that some founders did work in pairs on some limited edition creations (e.g., Villermaux and Nicolas, or Mercier and Nicolas) and signed accordingly their pieces, while still members of the association, as far as we know. But lacking a comparable vase signed by Rouppert and Roiseux, or any other combination involving Rouppert, this Ferry and Jeandidier piece hints at a previous arrangement, that was then expanded by the addition of Rouppert and Roiseux.

We can only guess the nature of the relationship between Jean Rouppert and Georges Ferry. Rouppert does say very little about it, but they were not on equal footing. Rouppert was a younger (by six years) upstart, with less than six months’ worth of experience as a painter decorator (as he himself recognises) compared to the 18 years of Ferry, who had worked both for Daum and Gallé. The boastful confidence of Rouppert’s letters should not mask the fact that he surely was the junior partner here, and the least experienced one – Hubert Roiseux and even Marie Henri Jeandidier were far more seasoned art glassworkers too.

Ultimately, the JEFFER project was derailed by the First World War: the war abruptly postponed the operation, even though it was already at a very advanced stage, with at least three of the four comrades enlisted in the army – only Ferry perhaps was excused from the service. The partners kept in touch at least in the beginning: in an important letter to Jean Rouppert dated from the 24th October 1914, Hubert Roiseux gave fresh news about the fate of the Gallé factory and its workers, many of them were already dead or missing17. He passed along greetings from Jeandidier, who had been removed from his safe job as a vaguemestre (military postman), as a punishment to his dereliction of duty, to be posted on the front line. But, unbeknownst to Roiseux, Jeandidier had already been killed in action a fortnight before, on the 8th October 1914, in Parvillers (Somme)18. The same letter from Roiseux hints at Ferry being ill and perhaps released from service, if indeed he is the man designated as “Ferri” with a faulty spelling. Hubert Roiseux himself managed to stay alive until the last year of the conflict, before getting killed on the 11th June 1918.

Rouppert never ceased working toward its goal the whole time, continuously drawing plants and flowers as models for his future endeavour. But he does not mention Ferry, whose activity during the war is not known. It’s quite possible that the latter went back to work for the Établissements Gallé in December 1914 or January 1915, when the factory reopened its workshops on a limited basis, but there’s no source so far to confirm this hypothesis19. In 1919, with two of their partners departed, Georges Ferry and Jean Rouppert each went their own way and their path never crossed again, as far as we know.

The Ferry signature and the Verrerie d’art Ferry.

Georges Ferry’s whereabouts between 1914 and 1926 remain unknown at this point. It seems implausible that he would have remained with Gallé after 1919, since most, if not all, the more ambitious decorators and designers left the company in 1919-1920. There was a strong demand for skilled glassworkers in Nancy in the early 1920s, with the creation of two new major artistic glassworks, the Cristalleries de Nancy and the Verrerie Delatte, without forgetting of course the smaller Société des graveurs d’art réunis around Paul Nicolas. The latter did not employ Georges Ferry, that much is certain from the extensively preserved archives of this cooperative. But a recruitment by another company is certainly a possibility.

In the 1920s, Georges Ferry tried to raise his status as a bona fide painter by sending some paintings to the salon of the Société des amis des arts in Nancy: he’s mentioned in a 1926 review of the salon for a local landscape20. He followed in this the custom of most designers and painter decorators : the same 1926 review mentions indeed another little known painter decorator, Georges Dethorey, who at the time must have just been recruited by the Établissements Gallé, as a successor for Jean Rouppert.

So, when did Georges Ferry become self-employed, and when did he establish his own glass studio? On the 1926 census, he gives his occupation as a self-employed painter decorator, or more exactly working for a company that bears his name, Ferry, that we can safely surmise he had himself created: this is the earliest known mention of his glasswork company. His son, Georges, 17 years old, works for him as a painter apprentice. The business appears in a February 1927 official survey on the regional industry. And that’s about it. As we’ll see below, pieces coming out of this glass studio were probably signed “G. Ferry, Nancy”, but not all of those can be ascribed to this period because it looks like he had already made some as early as the 1910s.

Among his employees, stands out one Albert Schwartz, another painter, whose bankruptcy is registered in December 192721. Presumably he went on to work for the Ferry studio.

The early 1930s were a brutal period for the art glass industry in Nancy and its area: all the major glasswork companies went under from the consequences of the world economic crisis, Delatte in 1931, the Muller Brothers in 1934, the Cristallerie de Nancy, in 1934, the Établissements Gallé in 1936 after a protracted end. By then, small studios like Paul Nicolas’ had disappeared or been reduced to one-man operations. The lack of information on the Verrerie d’art Ferry and the extreme rarity of his signed glass pieces suggests at the minimum that it did not escape this fate, if it made it at all past 1927.

The G. Ferry signature on glass and ceramic.

At this time, lacking further archives, one has to study the available pieces of glass and earthenware bearing a Ferry signature to sort out the sketchy history of this art glass production. There are three types of signatures with the name “G. Ferry”. It’s worth noting the initial G before the family name: Georges Ferry understood his was not an uncommon name – indeed there was at least another Ferry working in the Gallé factory, François Ferry, in 1911 – and this signature with an abbreviated first name reflects it.

One first type of signature is, in fact, composed with two names, “G. Ferry & / M. Jeandidier / Nancy”. It’s featured on a vase sold in Mâcon, in April 202122. M. Jeandidier must be the Marie Henri Jeandidier mentioned above in connection with the JEFFER secession project from Gallé. Obviously, it’s a pre-WW1 one and a critical clue regarding the formation process of the JEFFER team. It suggests that Georges Ferry and Marie Henri Jeandidier began working together either before they were approached by Jean Rouppert, or perhaps even while they were scheming with him about founding a common firm. The vase fits squarely inside the Gallé style of that period. It’s a small detail but the way the signature is designed, with the y’s leg extended by a stroke underlining the name, both in “Ferry” and “Nancy”, is highly reminiscent of the contemporary Gallé Mk III signature. The vase itself looks to be an acid-etched cameo two-layers, red on white glass, with a pattern of grapes that belongs to the usual Gallé botanical genre. It could very well pass for a Gallé product, if there was not some doubt about his shape, a 19 cm high straight tube, that does not belong to the standard Gallé repertory, it seems. So, the hypothesis that it represents some personal work, on their free time, from Ferry and Jeandidier, using some blank from the Gallé inventory looks uncertain. Jeandidier coming from Lunéville, there is a high probability that, if Ferry and he were working from another factory’s blanks, these would come from the Muller brothers in Croismare. It’s worth remembering that in that same period, Delatte was founding his art glass studio with blanks from Lunéville – or perhaps Portieux. Whatever the case, it’s clearly the personal work of the two Gallé decorators in the early 1910s, with July 1914 (and Jeandidier’s subsequent enlistment) as the latest possible date.

The second type of signature features the designer’s name and the location, “G. Ferry Nancy”. It’s the signature sported by the vase in Quittenbaum’s November 2021 sale. The signature’s writing style is a little different from the type 1, more stocky or squarish. The vase is a three layers cameo glass, green and violet on opalescent white, with an urn or amphora shape, 30.2 cm tall. The design theme is a river or lake landscape, with trees on the forefront and a man in a rowing boat. The scene compares well enough with similar Gallé landscapes, designed by both Louis Hestaux and Paul Nicolas in the 1910s and early 1920s. It should be noted that human characters are seldom featured on Gallé landscapes, though there are a few series of this kind, with a man passing by on a bridge or fishing along the river. The three different landscapes attributed so far to Georges Ferry all have one. Because of its superior quality (it seems) compared to the grape vase, the making of this landscape can probably be placed in the mid-1920s and linked to the Verrerie d’art Ferry, rather than to his first tries in the 1910s. But it still largely is a matter of personal appreciation at this point.

The third type of signature has “G. Ferry”, with no added location – unless the auctioneer’s description is faulty. This mark is present on another river landscape design, a simple two layers cameo, red on clear glass, goblet shaped, 10 cm high vase. The details of the scenery are exquisite: a man carrying a load on his back is crossing a single arched river bridge, with birds hovering above the trees and a small village in the background. Even while he was being limited by the monochromatic layer, the painter has been able to render at least three different shades, and to picture with great effects the light plays and reflections on the water. Again, the design and its execution are closely related to Établissements Gallé (and Nicolas/D’Argental) contemporary creations, and it’s not difficult to recognise the craftwork of a Gallé alumnus. Unfortunately, the signature was not pictured in the auction catalogue and it was not possible to get a new picture, for the sale was too old (2003). What the pictures show, though, is a monogram made of two letters, AR or RA, etched in white against the sky in the upper middle part of the back face: this makes this vase a commemorative marriage glass, of the kind made by Gallé and Daum, among others, in late 19th and early 20th c. The monogram is a customised inscription with the still unidentified groom and bride’s initials. It could have been etched on order, if this piece belongs to a commercial series, but it could also be a unique piece, as were personal works from the Gallé workers. Either way, there’s no telling its date.

The whole selection reminds of Paul Nicolas’ venture between 1920 and 1924, when glass pieces coming from his studio could feature generic signatures as well as more personal ones, either with his name alone or with one of his most trusted collaborators, like Mercier, Villermaux or Windeck. The comparison goes beyond the technical matter of the signatures: Nicolas succeeded where Ferry failed, at least regarding the critical reception of his works, and because he was backed up by a powerful glasswork company (Saint-Louis), but both show the frustration of Gallé’s designers, on the face of its turn toward industrial series, as well as their will to get a better share of their commercial success.

Painted ceramics.

One last category of Ferry-signed artworks belongs to a different genre: these are painted ceramics, often bearing a “Céramique d’art Marseille” label, and also simply signed G. Ferry, with no location. Some were auctioned off in Salon de Provence in 2017, while another one was sold on eBay from the same general area. Given what is known about Ferry’s biography – he remarried in Marseille and died in Salon de Provence in 1948 – there’s little reason to doubt that Georges Eugène Ferry is the creator of these ceramics. Of course, the possibility still stands that it’s another G. Ferry, perhaps even his son, also named Georges, who began working as a painter for his father and whose whereabouts remain unknown at this time.

But two ceramic pieces in question here have clear similarities with Georges Eugène Ferry’s earlier works : first, an amphora shaped vase with an olive picking scene represents again a regional landscape with dark figures on a bright background, and the man’s design is quite close in style to the rowing man on the Quittenbaum vase. Second, a globular vase has two river landscapes, again very similar to his paintings on glass from Lorraine.

These two examples come from the two different lines of these ceramics that can be found. The first one is this series of painted amphora-shaped vases, with square handles and a glossy finish. The decor combines painted bucolic scenes from Provence, like the shepherd below, and applied cicadas on the vase’s shoulder.

The second category of these late artworks consists in ceramic globular vases, with a black and white pulverised surface in which painted medallions are inserted. One has a painted pattern of highly stylised flowers, in the Art Deco style, also signed G. Ferry. The composition, with this limited square painted patch on the vase’s top and shoulder, as well as the shape are reminiscent of glass pieces from the Nancy glasswork houses like André Delatte and the Verreries de l’Est. It hints at the possibility that Ferry designed some similar artworks for another company, or at the very least that he drew inspiration from them for his own.

Conclusion

A full account of Georges Ferry and his various endeavours in the art glassmaking milieu of Nancy remains unreachable at this time. More research is needed in local archives, in particular, to sketch the brief history of the Verrerie d’art Ferry. One can hope however that this first paper on the subject will foster some interest for this quite interesting character and bring out to light new documents or, more realistically perhaps, other glass and ceramic pieces which will help fleshing out his biography and the history of his verrerie d’art. At this point, Georges Ferry illustrates the strong vitality of the art glassmaking milieu of Nancy throughout the 1900’s-1920’s, when the city was in all but name the French capital of this trade.

© Samuel Provost, 18 December 2021.

Footnotes

My thanks go to the Quittenbaum auction house for providing me detailed pictures of the vase and for allowing their publication on this page.

The company he worked for was not named at that time, since this information was not registered on the 1896 census, contrary to other years.

Bardin 2004, p. 77-78.

Bardin identified 47 students and more than 300 drawings and 43 notebooks in the Daum archives, but the only dated ones were from the 1912-1914 and 1921-1924 periods (Bardin 2004, p. 78).

AD 54, 1 R 1360, Registre des matricules, classe 1901, Toul, no 1256.

He is not included in François Le Tacon’s lists of Gallé employees.

Born in 1879, he had married Georges’ older sister, Rosalie Ferry, before 1906. He was then a witness at Georges Ferry’s wedding with Pauline Signart.

Me Caroline Tillie-Chauchard, Tableaux XIXe-XXe, Céramiques du Sud-Est XIXe-XXe, 7 December 2013, Salon de Provence, Dame Marteau, lot 15 and 16.

Marie-Hélène Stein (formerly Belling), who completed her MA dissertation on Jean Rouppert under my supervision in 2016, is to be credited for the discovery of this artist’s major role as Établissements Gallé’s chief designer for glass in the early 1920s. She benefited, as I did at the same time, from the invaluable help of Ronald Müller who provided us full access to the relevant archives and must be warmly thanked and congratulated for his continuous efforts to publish Rouppert’s works. Marie-Hélène Stein published some of her findings in a paper published in the Association des Amis du Musée de l’École de Nancy’s journal, Arts Nouveaux (Stein 2017).

Letter from Jean Rouppert to Madeleine Labouré, 27 August 1913: Müller 2007, p. 72.

It shoud be noted that there’s no hyphen between the first two first names: Jeandidier was called Marie Henri, not Marie-Henri.

Letter from Jean Rouppert to Madeleine Labouré, 16 February 1914: Müller 2007, p. 74.

Translation: “On Sunday afternoon we had a meeting at the home of one of my future partners. There are four of us now. We are going to form a company under the common name of Jeffer. One is in charge of the representative and commercial part. The second is in charge of the engraving and glassmaking part. The third, in collaboration with me, is in charge of the artistic and decorative part. He will do the landscape and the stained glass, while I will remain alone in charge of all that will be figures and characters (...) With this system, the Jeffer pseudonym covers us and allows us to wait while keeping our place at Gallé.”

Letter from Jean Rouppert to Madeleine Labouré, 20 February 1914: Müller 2007, p. 75-76.

Translation: “I am the one who established the statutes; they are adamant. Whoever would shirk his duties would lose all profit and would be immediately terminated [sic]. On the other hand, there are only two creators out of the four of us. R[oiseux], the one I was telling you about, is an excellent worker, but only a worker. He knows how to cut with the wheel, knows glassmaking and a little chemistry. J[eandidier], also a good decorator, knows porcelain, ceramics, enamels and terracotta. As for creative artists there are only F[erry] and me. J[eandidier] and R[oiseux] are thus under our dependence, they cannot try anything without us who are the head.

In F[erry], I have every confidence. He has built himself a house on credit. But the land and the house are not paid for (about 18,000 francs) and his savings are small. This one wants to succeed because necessity pushes him.

Then, he is very good at decorative arrangements and stained glass, he makes delicate landscapes and flowers, but he is mediocre in characters and physiognomies. Everything he does, I can do and even what he does not do (...)

It is true that on the practical question, I am the least skilled being a newcomer in the profession.”

The avenue de Boufflers and its neighbourhood sees an intense building activity in the 1920s, with projects from renowned architects : see Gilles Marseille. “Pour un nouvel art de vivre, Dispositifs innovants dans l’habitat nancéien de l’Entre- deux-guerres”, Cahiers du LHAC, École Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture de Nancy, 2015, pp.124- 139 (hal-02987392).

Archives Jean Rouppert, courtesy of Ronald Muller.

His death was officially recorded by the court in his hometown of Lunéville on 17th January 1916 (Bulletin de Meurthe-et-Moselle, 1st February 1916). His honorific diploma was left unclaimed which suggests that, having lost his mother in February 1914 (Journal de la Meurthe et des Vosges, 8-9th February 1914), he had no close family left.

His name does not appear in the Gallé-Perdrizet family correspondance during this period. But there’s no reason it should if he was considered as just another painter decorator. These letters do not mention either Jean Rouppert for instance in 1919, when he was appointed as chief designer for the glass series.

Maurice Garçot, “Le Salon des Amis des arts, VI, D’un peintre à l’autre”, Le Télégramme des Vosges, 18 October 1926.

Archives départementales de Meurthe-et-Moselle, Tribunal de commerce de Nancy, Faillites, dossiers individuels, 6 U 2/851.

Trésors Hautes Epoques, Mâcon, 29th April 2021, lot 454. The auctioneer misread the name as “Jeanvivier”.

Bibliography

Belling M.-H. 2017, “Jean Rouppert, un dessinateur chez Gallé (1913-1924)”, Arts Nouveaux, 33, p. 24-31.

Müller R. 2007, Jean Rouppert, un dessinateur dans la tourmente de la Grande Guerre, L’Harmattan.

How to cite this article : Samuel Provost, “Georges Ferry (1881-1948) and his short-lived Verrerie d’art Ferry in Nancy. The unrealised ambitions of a little known Gallé alumnus.”, Newsletter on Art Nouveau Craftwork & Industry, no 17, 18 December 2021 [link].

Bonjour et merci pour ce post très utiles ! J'ai en ma possession un vase très atypique de l'artiste G ferry en forme d'essain d'abeilles avec un semi décor floral....je peux vs envoyer des photos également par e-mail d'autant plus que pour votre post j'ai egalement le nom de l'atelier qu'il a créé à Marseille...

Bien cordialement

Ahmed