Glaïeuls, a case study of a popular floral series by the Établissements Gallé.

Gallé Resellers’ catalogues and the chronology of a cameo art glass series.

Getting an accurate chronology on a Gallé industrial series is a notoriously difficult task, sometimes far harder than dating a masterpiece from Émile Gallé. The general lack of commercial or exhibition catalogues, the missing archives, the huge number of different series, the length of their production run all factor in making a precise assessment of a design’s date all but a pipe dream, at least in most cases. All is not gloom and doom however: the last decade has seen many important archives from Gallé designers (Louis Hestaux, Auguste Herbst, Jean Rouppert) reappearing on the market or, better yet, in public collections, like the Musée de l’École de Nancy, and there are hints that perhaps the best is yet to come in this regard. Moreover, other neglected or hard to find public sources, in particular printed material like the general stores’ advertisements in the newspapers and magazines or the specialised annual catalogues from retailers, are quickly becoming easier to search, thanks to the rapid progress of digitised archives as well as the rise of online marketplaces for such items.

The slow, but steady increment of publicly available information allows thus to reconsider the proposed date of some series, sometimes with a great deal of precision. Such is the case of a floral cameo glass series, which features among the most appreciated, but whose creation has also been assigned to widely different periods, the blue on yellow Glaïeuls, also sometimes identified as Iris Grandiflora and even Lys tigré (sic).

It happens that this series’ creation as well as its designer’s identity are well documented enough, compared to similar floral patterns, thanks to the preservation of several stencils as well as the reproduction of some specimens in a commercial catalogue. For this reason, it seemed interesting, to try making a complete overview of this series, as a taste of what would entail an exhaustive catalogue raisonné of the Gallé line of glass products.

The Glaïeuls (Gladioli) series and its variants.

A Gallé cameo glass series is defined by two variables, a decorative pattern and a combination of coloured glass overlays that can be applied to a range of widely different shapes and sizes, to achieve a maximal variety at a minimal cost. Although each variation of the design is made in a limited number of copies, the large number of available combinations insures a sizeable output and revenue from this series. When and if it proves successful, additional production runs in the following years can carry on the design with small changes, like a new background colour or additional shapes. The goal is to impart the buyers of these luxury items with the feel of exclusivity when these are, in fact, mass-produced industrial series.

As for the Glaïeuls, the basic design is a sprig of gladiolus flowers in a distinct three-colours combination, violet over parma blue on a bright yellow background (with white and rose variants). The vivid contrast achieved by the gradual etching of the external dark layer revealing the bright light blue of the blooming flowers as well as the spearhead-like long leaves curling around the vase make this design highly effective.

The shapes and colours.

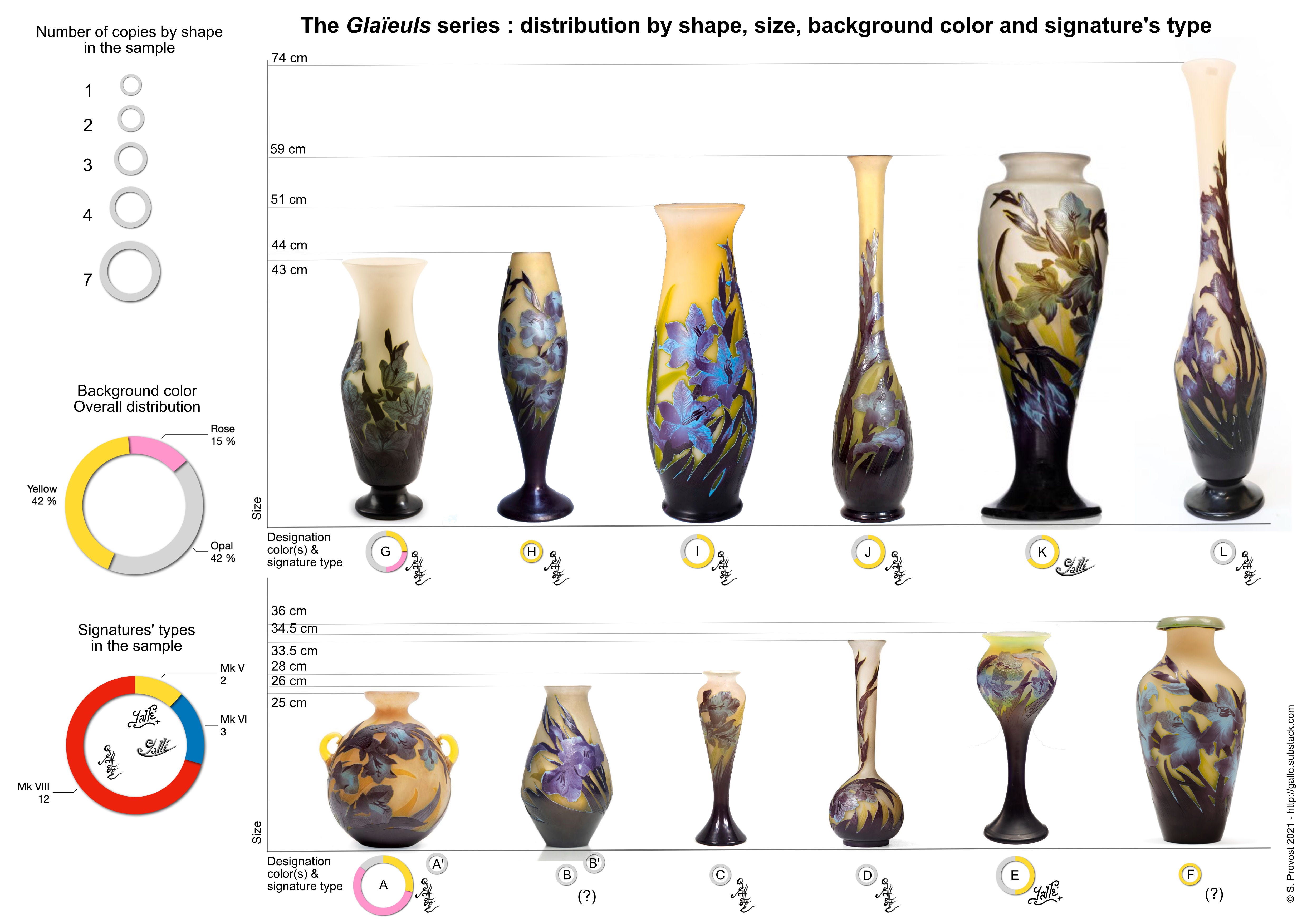

A systematic search across the usual available database1 and catalogues yielded a total of 36 specimens featuring this design, most of them sold in auctions during the last 15 years or so2. 34 of these glass pieces were vases, belonging to 14 different shapes, the last one being the rather impressive lamp published by Duncan and De Bartha in their book’s pictures album3. Significantly, two of the most important museum collections, as far as Gallé industrial art glass is concerned, include one specimen, and what’s more, with the same shape and colour type: the Kitazawa museum in Tokyo and the Glasmuseum in Düsseldorf each own one of the chalice shaped Glaïeuls4. A close variant of this series, the so-called diabolo-shaped vases featuring the same violet/blue/yellow gladioli, with the addition of a butterfly over them, is omitted intentionally from this selection, although it could be considered as a sub-series of this theme.

The original array of available shapes for this series was almost certainly smaller: the Gallé depot manager Albert Daigueperce once confided to the art historian Françoise Thérèse Charpentier that a series usually came in an initial choice of 6 to 11 shapes, and this remark does hold true so far5. At this stage of the research, there is no way of knowing which shapes constituted the initial offering. Therefore, the figure above shows all the vases’ shapes found in our sample, scaled to size, labelled by a letter (A to L), in ascending height. This purely arbitrary criterion illustrates nonetheless the roughly equal distribution across the product line of various characteristics – wide or narrow mouth, foot or simple base, among others – as well as the effort to have every general class of traditional vase shapes represented, solifleurs, urns, chalice, flask, potiches, and so on. For simplicity, the chart does not show the rarer variants of some shapes (A and B), lacking (A’) or adding (B’) applied handles6. It’s worth remarking that these applied parts were getting rarer in the 1920s, and that may be, with the signatures (see below), part of the reason the series is sometimes wildly misdated (see for instance the three variants of the type A on the picture below) – on the wrong assumption that Établissements Gallé had abandoned all forms of hot glass additional work on their vases by the 1920s.

It speaks of the Glaïeuls commercial success that additional forms were made as well as colour alternatives for its background because, here again, while different coloured series could be made from the start for a given pattern, it usually happened as a way to further its shelf life, so to speak. There were thus three background colours in production, bright yellow, opalescent white and light rose. Yellow and white were almost in equal part the commonest, while rose was limited to just two series (as far as I can determine), type A and G, but it was a big part of the former’s output (4 out of 7 specimens). The fact that all the shapes represented by more than one specimen in our sample do have background colour variants, except for types L and J, hints at the replication of this renewal across the whole model line. That each specific model is not present in more than three copies, and sometimes in only one, reflects the limited quantities that were made. But with a potential of 42 different variations, not counting the additional option of multiple sizes for each (see below), this series’ output certainly surpassed several hundred copies and perhaps more than one thousand. One has to remember René Dézavelle’s testimony on the matter: large vases were made in 12 copies, smaller ones in 20s7.

Size mattered a lot in determining the volume for a given series because the price of a vase was almost always a direct function of its size. The 12 basic different shapes the Gladioli came in, measure from a respectable 25 cm high to a behemoth 74 cm. Half the range of shapes had a size over 42 cm, a very unusual distribution in the Gallé series, even in the 1920s. In the 1927 Gallé sales catalogue (from the Rakow Library at the Corning Museum of Glass), the average size of the 354 models on display is 27 cm (ranging from just 5 cm to 70 cm high, lamps excluded), which is just 1 cm taller than the smallest available Glaïeuls.

Regarding the sizes still, the question remains open if one or several basic Glaïeuls shapes were made in different ones, to widen further the choice. This was a common practice for the most popular shapes, which were often available in (at least) three different sizes with the same pattern — see for instance plate 50 of the 1927 catalogue showing 3 identical perfume bottles side by side, measuring 15, 17 and 20 cm. A close study of the catalogue would yield many other examples. But our sample of Glaïeuls only has one such instance, for the type I, known from only two specimens, one 43 cm tall and the other 51 cm – assuming measurements were right, of course8. This may be a statistical oddity due to the limited sample, or it could also reflect the exclusive nature of this series, which was not to be diluted by making smaller copies. Regarding the type I, it’s worth noting that the lesser of the two versions, with 43 cm, is still way taller than the average Gallé piece of glass. It’s also perhaps not coincidental if the most common shape for this series with 9 copies (in 3 colours), the moon flask with applied handles (type A), was found in one size only (25 cm), while other sizes existed in other series (14, 21, 30 and even 44 cm) going back to Émile Gallé’s lifetime.

Another consideration was probably factored in. The glass piece’s shape – as well as its function in some cases, like the lamps – represents a major technical constraint: all forms are not well suited for a given design. The Glaïeuls (Gladioli) series is a case in point. This tall and slender flower is a far better fit for high tapered shapes with narrow necks, like soliflores, than for lower and wider shapes, like jardinières or bowl-like ones. This does not mean, however, that they could not be accommodated, as several shapes of the Glaïeuls series can attest: The moon-shaped flask (type A), for instance, and the chalice (type E), have the flower’s stem curling around the vase’s body. But they are exceptions.

In other words, the Glaïeuls pattern was almost exclusively designed for tall vases, i.e. for a high-priced prestige series. Confirmation comes from its glass composition too: with three overlays, the Glaïeulsbelonged to the higher end of the Gallé cameo glass line, at a time when most series had only one or two.

The signatures and the series’ chronology.

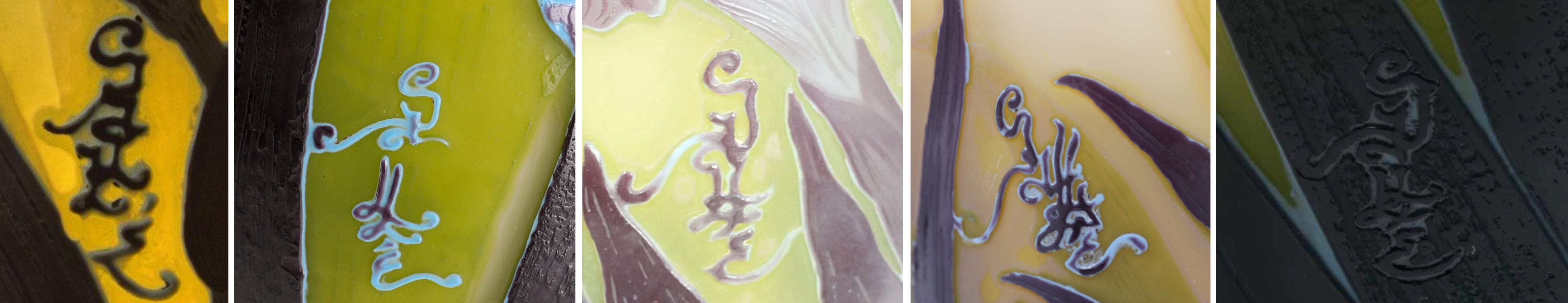

Another hint regarding the special status of this series can be found in the signatures. For once, they are easy enough to study because they are often pictured on the auctions sites. The large size of the vases means that they usually receive a special treatment from the appraiser, with several pictures. Even when the signature is not a specific target of the photo shoot, it’s bound to be visible somewhere on one of the pictures. As I explained elsewhere, the Établissements Gallé’s signature is a mark meant to be easy to spot, that is part of the decorative pattern. It’s all the more true for this series. That explains the exceptional rate of known signatures in our sample. Only three series (B, B’ and F) do not have yet their signature known.

The prevalent signature’s type featured on the Glaïeuls vases is by far the Mk VIII one, in its vertical iteration, which is one of the most ornate late Gallé signatures — often dubbed the “Japanese styled” signature. Other attested signatures are the Mk V and the Mk VI types, each on one shape only (respectively types E and K) — but consistently so. In every type with at least two signed known specimens, the signature remains the same, even when these specimens have a different background colour. That’s the natural consequence of using signatures on stencils and pouncing patterns, a standard practice for the big glass pieces, rather than drawing them freely manually, as it was done for the small pieces. The same signature was therefore replicated across the line, even for different series and production runs.

The two shapes sporting different signatures, E and K, share a characteristic that may help understand this change. They both have a high foot covered in the dark external overlay, without the possibility to etch on cameo the signature on a lighter background — at least not without relocating it much higher on the vase’s body than what was usually the case on floral series. As a result, and according to the custom in such cases, the signature is etched in intaglio on the foot. This was not the only solution: there is at least one specimen of another series, the type G one, where the Mk VIII signature is etched in cameo against the background of a leaf from the same external dark layer, with only a thin light blue line outlining the signature’s drawing. This alternative was not much more satisfactory, regarding the mark’s visibility, than a simple intaglio signature, though, which explains its scarcity.

The main question these different signatures ask is whether the change is motivated by the design’s characteristics, or if it reflects an altogether different chronology. In the current hypothesis regarding the signatures’ system in use by the Établissements Gallé during the 1920s, the Mk V is associated with Jean Rouppert’s turn as chief designer for glass, between 1919 and 1924, while the Mk VI takes its place in 1925 as the mainstay signature, remaining so throughout the late 1920s and 1930s, with the Mk VIII as a later alternate. A strict application of this system to the Glaïeuls series would result in the following reconstruction of its history: a slow and limited introduction in the early 1920s, with the types E and K, in that order, and perhaps a few others, still unaccounted for, before a full-blown roll-out with the eight to ten other shapes, in the late 1920s. This scenario is by no mean impossible, but it runs counter the usual Gallé practice – new industrial series were rarely, if ever, introduced in only one shape – and looks suspect for this reason. Other hypothesises can yet be entertained: a legacy use of the Mk V past 1924, for reasons that would have to be explained, would reconcile the overall chronology and allow pushing it forward to 1927 or even later; on the other hand, a reconsideration of the Mk VIII’s creation, to make it at least in part contemporary to the Mk V, would also reunify the series by placing it before 1925. In this third scenario, the type K Glaïeuls would be a later addition to the original line-up.

There is no way to choose between these narratives without resorting to external documentation. Fortunately, several pieces of evidence do exist on the matter.

(To read the complete analysis, please subscribe)