“Le Lac de Côme” series by Auguste Herbst for the Établissements Gallé.

When a long envisioned personal project came to fruition.

The Lake of Como vases feature among the most iconic late industrial glass series by the Établissements Gallé. While they’re not among the rarest ones, they fetch routinely more than €10,000 in auctions, and they are highly sought after. Having made regular use, in previous articles, of this series to date other glass from the 1920s (including the Rio de Janeiro vases), I would be remiss if I did not expose the reasoning behind this chronology. For it is far from accepted : the conventional wisdom places the beginning of this design before the First World War (1), in line with other major landscapes series, like the politically laden La Ligne bleue des Vosges, a 1914 production building on earlier Vosges mountains designs. But most of the specimens of the Lake of Como vases bear later signatures’ types (Mk IV, Mk VI or Mk VIII), from the 1920s, or the Mk III one, which we now know was in use until late 1920 and featured sometimes even on later pieces. There are therefore real reasons to doubt the first creation of this series before 1919.

The various versions of the Lake of Como and its inspiration.

In many aspects, this Lake of Como series is unique among the landscapes vases: it’s the only Italian landscape, and in fact one of very few identified foreign views. Among the numerous Alpine mountains landscapes vases from the Gallé line, it’s really the only one referenced by a non-generic name. Even the vases depicting an easily recognisable landmark like the Matterhorn Mount (Mt Cervin) are seldom named after it. Disregarding the wood marquetry series and their multiple desert views, or the exotic animals themed glass series, the Rio de Janeiro view is really the only other design in the same category.

The two series share other characteristics : they have multiple variants and were produced over a rather long period, judging by the different signatures that they feature, which is a testimony of their popularity. They are still today among the most prized Gallé industrial vases. But the Lake of Como has the distinct privilege of being the only landscape series, to my knowledge, to be restricted to a limited range of vase shapes and sizes.

When a new landscape or botanical design was introduced in the Gallé line, it was etched on various shapes whose number usually ranged from 10 to 15. This variety could also be accrued by the production of different sizes for the same shape. This was of course a marketing decision to get the most sales from these novelties. Very few designs were limited to a specific shape and size, outside of course the relief vases of the late 1920s, for which the limitation was both technical and financial : the moulds being sculpted for a given design could not be used for another one. The decision, therefore, not to adapt the Lake of Como decor to other shapes than the original ovoid one (with only one exception), which it quickly and strongly became associated with, signals the will to keep this series at the higher end of the Gallé line. The same remark goes also for the production of successive multiple variants in the design — within this constrained shape and sizes and presumably each in small numbers. In other words, it looks like the Lake of Como vases were produced as a prestige series on the sole merits of its particular landscape design and the special care that was put into its production, compared to other landscapes. The 1927 sales album kept in the Rakow library supports this view : one 36 cm tall specimen of the vase is featured on plate 58 with three other landscapes of roughly comparable size, and it is by far the costliest of the four ($120 against $44, $72 and $96 respectively — gross sales prices, one can assume). There are far bigger (up to 55 cm high) and pricier (up to $380) vases on the catalogue, but in the 35-40 cm range, the Lake of Como stands as one of the most expensive.

A mountain lake landscape with a conspicuous human presence.

The first difficulty in rounding up the different variants lies in the fact that the design was not named as such and inscribed on the vase, contrary to what’s the case for the Ligne bleue des Vosges or the Rio de Janeiro. Because many, if not most, of the Alpine landscapes vases feature a lake in the foreground, some of them from the French or Swiss Alps have been wrongly — and perhaps sometimes wilfully, to profit from the higher associated value (2) — labeled as belonging to the Lake of Como series. On the flip-side, it also happens that vases from this series are misidentified as more common mountains landscapes vases, in this case harming their owner.

But the confusion is easily dispelled. What sets apart the real Lake of Como landscape is the much visible presence and influence of man over nature compared to his quasi absence or at least its more subdued presence in all the other mountain ones. In the latter, you can sometimes spot a path here, a log cabin there, and that’s all. The Lake of Como is dominated front and foremost by the elements of a grand Italian villa garden : the architectural feature of the balustrade, the domesticated tree species specific to these gardens, benefiting from the gentler climate than in the French or Swiss Alps — the cypress and the eucalyptus —, the peacock as a frequent ornemental bird in this setting. Formidable castles or church towers dot the islands in the middle of the lake or its shores in the background. This is not the wild and untouched nature of the high Alpine mountains but the softer one of the leisurely coastal lake resorts.

This kind of landscape belongs to a well established pictorial tradition in the late 19th and early 20th c. The great Alpine lakes of Northern Italy are practically part of the Grand Tour and the Lake of Como is famous among them for its elaborated aristocratic villas and gardens — small Versailles on the lake as the saying goes. There is therefore practically a cottage industry of painters and photographers producing such celebrated views of the lakeside like, for instance, the Lodge on the Lake of Como, by the Danish landscape painter Carl Frederic Aagaard (1833-1895). This painting has all the attributes that hallmark these lakeside views : the terrace garden with its lush Mediterranean vegetation in the foreground, the architectural features, here a loggia and a grand stair with an impressive balustrade, and of course in a slightly hazy distance the steep slopes of the mountains plunging into the waters of the lake. The garden features several tall terracotta vases or flower pots that evoke the very shape of some Lake of Como series : here’s a hint that the chosen form and tall size of these Gallé vases is meant in itself to remind of these gardens.

With the advent of cheap photographical reproduction, mainly with postcards, the number and variety of available lake views soared at the turn of the 20th c. These photographs are composed like paintings for the most part and show the same characteristics. Their production answers the appetite of a growing tourism and insures a wide dissemination of these landscapes views in Europe. The next step is their reproduction on decorative objects. For the Établissements Gallé, the Lake of Como view combined the familiarity of an Alpine landscape, the light exoticism of the Mediterranean vegetation and the prestige of a famous holiday destination : it was therefore at the same time a natural fit and a welcome novelty in the Gallé line.

The Lake of Como variants : types and numbers

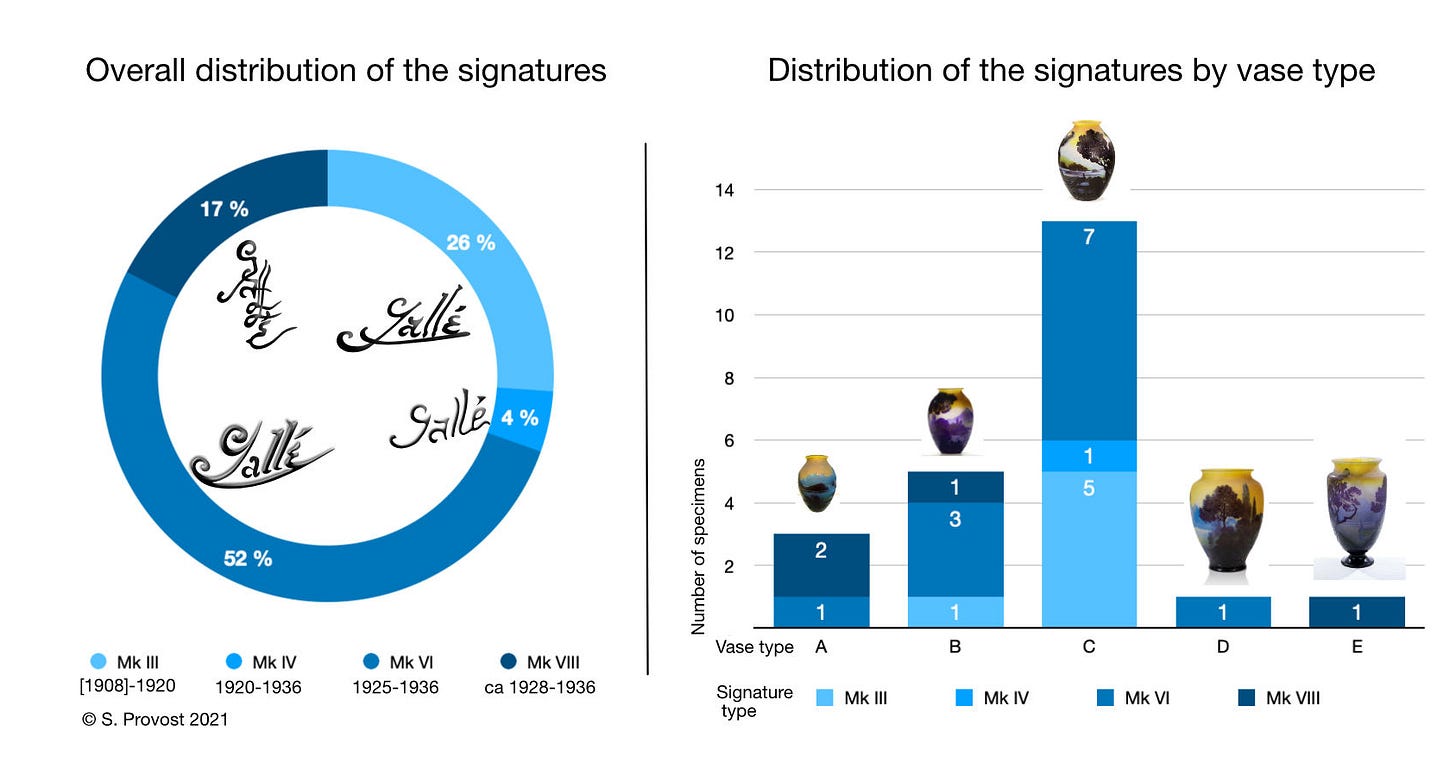

Several variants of the Lake of Como series are known from the antiques market today. The two main ones are depicted side by side in Duncan and De Bartha’s book on Gallé glass (3), and they represent the vast majority of the known vases rightly traded under this name, as well as the few ones that escaped a proper identification. The graphic above shows the differences in shape and size for the five main types of Lake of Como I could identify from the auctions and dealers archives freely available (4) on the Internet since 2000, for a total of 26 specimens. Given the long time span, it’s quite possible that some of these are in fact the same vases, even though I tried to eliminate these doubles : the poor quality of the pictures provided in some cases unfortunately does not always allow a conclusive comparison. I feel nonetheless fairly confident that the few twins that might have escaped my scrutiny do not sensibly alter the overall picture. It is of course also possible that other variants yet in shape and size are not represented here : as always, I welcome any correction from the readers in that matter, and I will accordingly update the graphic in the future to allow for these omissions. The five shapes are designated by a letter, in a rising order, from the smallest (A, 20 cm) to the tallest one (E, 52 cm) (5). The darker coloured portion of the ring enclosing the letter is meant to give a rough estimate of their frequency in the sample.

Several important remarks have to be made from the onset about this sample. Each shape is limited to one size : the three smaller ones evidently, A, B and C are very close to one another but not identical, and their ovoid shape — which has become closely associated with the design — is not known for the upper range of available sizes. Within each type/size, several variants exist, but they differ only by the colour scheme (and therefore sometimes by the number of glass layers), and not by the scenery design. For instance, all the C landscapes have this same design of a peacock standing on the balustrade, but they are available in four or five different hues, from the classic three layers violet-blue-yellow (and therefore green) to an almost monochrome blue, declined in many shades by the acid etching (6) (see the picture below).

As for the identification of the exact location depicted on these five scenes, it remains unsolved for the moment. Each of these five landscapes is constructed in the same way, which is why they can be grouped together in the first place : on the foreground a lone tree (usually a eucalyptus) and a small grove (usually some cypresses) are associated with an architectural feature (a balustrade on A, B and C, a retaining wall on D) on which stands a peacock (C) or a flock of pigeons (B), while the middle ground shows the lake with a peninsula (A, B) or an island (C), featuring some kind of building (a castle, B, or a villa, C and D with the statue at the end of a dock), while sharp mountains peaks stand at the horizon. The “waters divided by land” theme suggests a peninsula on the lake shores or the land extension between the two southern parts of the lake, but the comparison with actual photographs remains so far inconclusive. The areas around Colico with the peninsula of the Piona abbey, Menaggio in the center east section of the lake, Bellagio at the parting point with the Lago di Lecco, or the Isola Comacina along the south-east shores all look like possible but partial matches (see the map below). The Monte Muggio and Monte Legnone offer close enough profiles with the two main summits appearing on the type B vase (see the old postcard above) : this landscape could be a view from the shore just south of Menaggio. Readers better acquainted with this area are welcome to disagree and send me their hypothesis.

Some artistic licence with reality must of course be accounted for. These are simplified landscapes. The distinct possibility also exists that the Lake of Como generic name is partly mistaken and that some of these landscapes were drawn from other North Italian lakes.

There were thus at least five distinct views of the Lake of Como featured on Gallé vases, each one potentially produced perhaps in four or five different coloured versions, maybe more. This would amount to 20-25 different models during its production run, which is not inconceivable even for a high range product, given that it spanned more than a decade, as we shall see. According to Dézavelle’s testimony, the taller vase series were made in batches of 10 to 12 specimens — at least in his time in the 1920s (7): this looks consistent enough with what can be observed on the photographs from the different workshops of the factory where unfinished and semifinished glass pieces are awaiting their turn in wooden boxes. A quick and rough total estimate would be that more than 100 copies of the various Lake of Como vase have been made by Établissements Gallé. Dézavelle himself, in his crucial discussion of this series (see below) seem to downplay the numbers, writing that “a few vases were made for the Leipzig fair which, together with the Lyon fair, provided work for the whole year” (8). But over ten years or more, the estimated total would amount to about ten copies per year, which certainly qualifies as “a few” vases compared to a total yearly output in the thousands. Another way to put it is that the Lake of Como series perhaps saw one new variant coming out each year on average.

All five models were not produced in the same numbers : the statistical distribution of our sample, where the B and C models account for more than three quarters of the specimens (with 27% and 52% respectively), suggests that the two bigger sizes/designs, but also, more surprisingly perhaps, the smallest one, had a far more limited production run. Different factors were at play here. The taller vases were too expensive while the smallest ones were not big enough to do justice to their design : the landscape had to be simplified — that’s not per chance that it’s in this category one can find misidentified Lake of Como specimens.

The signatures and the chronological distribution of the variants

The distribution of signatures in our sample suggests that its production was drawn out over a long period of time. All the specimens do not have a visible signature, but 23 of the 26 do, and they feature an interesting variety of signatures (see the graphic above). The following analysis of these signatures assume of course that the sample is statistically significant, despite the relatively low numbers involved. It should therefore be considered as a provisional study whose results could be altered by a few new discoveries. Only four different signatures are attested with a theoretical chronological range from 1908 to 1936 : Mk III (1908-1920), Mk IV (1920-1936), Mk VI (1925-1936), Mk VIII (ca. 1928-1936). The dominant signature, featured on more than half the specimens, is the Mk VI, which is expected, since it’s the main one on large pieces from the second half of the 1920s. Conversely, the rarest one is the Mk IV (only one copy on a C type), which is also expected because it was largely limited to the smallest glass pieces. The surprise here is to find it on a C type vase (35 cm) and not on a smaller version (A or B). Another rare signature is the Mk VIIIa (the vertical variant of the Mk VIII), on four vases only, but that’s consistent with this very late and uncommon mark in general. Finally, the second most frequent signature is the Mk III, present on a quarter of the sample, corresponding to the majority of the vases made before 1925.

The starting date of the production cannot be determined from the signatures : that’s the general problem with the Mk III signature whose persistence across more than a decade, straddling the period of the war, creates all kinds of difficulties. Its subtypes do not conclusively help us either : five are plain Mk III while only one belongs to the Mk IIIb subtype (ending -é rather than -έ). The Mk IIIa subtype is absent in the sample. That may or may not be significant : it seems that this variant, with the ending small loop joining the -έ with the underscore, may have been dropped after 1916, or at the very least that the Mk III and Mk IIIb are dominant in the 1918-1920 period. But these subtypes were in use well before that too. We’ll have to count on other factors to try to pinpoint the date of creation of this design.

More importantly, there is one conspicuous absence among these marks : there’s no Mk V signed vase in the sample. This means either that this series ceased to be produced between 1920 and 1924 (unlikely, given its apparent success and Dézavelle’s testimony), or that the vases were sporting another signature. One obvious candidate is the Mk IV but, as we’ve seen, it’s present on only one specimen, and it’s unlikely to have been much more widely used since it’s usually selected to mark the lesser productions. It’s also a mark that could be dated much later, but as we’ll see briefly, this would not be the preferable option. The alternative solution is that the Mk III continued to mark these large vases after 1920. While this goes against the general signatures' chronology, it could be explained by the continuous use of the design’s original stencils — because of the limited numbers involved — rather than by some mistakes. This would also be congruent with the idea that the Mk V was reserved to Rouppert’s creations. Whatever the case, these Mk III signed Lake of Como vases hint at a perhaps necessary revision of the signatures scheme. It should be noted though, that any Mk III vase attributed to the 1920-1924 period is taken out from the count of the pre-1920 series. This has obvious consequences for the overall chronology of the design, making an early introduction (pre-1918) less probable.

Another general remark to be made regards the signatures’ location on the vases, for it has an obvious correlation with the mark’s type : the Mk III and Mk IV signatures are always etched in cameo above the railing, to the left of the peacock on C vases, or to the left of the pigeons flock on B vases, and thus highly visible against the light blue background of the lake’s waters. The Mk VI and Mk VIII, on the contrary, are etched in cameo in the lower part of the decor, usually between two uprights of the balustrade, against the dark background of the ground or vegetation, and so much more discrete. There was obviously a change of practice here around 1925, which gives us a hint regarding the chronology of the Mk IV specimen, more likely to belong to the 1920-1924 period.

Finally, when it comes to the study of these signatures, their distribution among the different models gives a good sense of the series’ evolution. The main type, as we’ve seen, is the C one, with the peacock : it was most probably the original design, and it continued to be produced during the whole period. Its smaller version, with the pigeons instead of the peacock (B), shared probably the same chronology. The signatures thus confirm that these two designs were the iconic initial versions of the landscape. The three other versions, with their Mk VI and Mk VIII signatures, were introduced in the second half of the 1920s, in a visible attempt to expand the market for this popular series, both with smaller and bigger models. Their modest numbers suggest they were short-lived or introduced toward the very end of the Etablissements Gallé history.

The design’s origins according to René Dézavelle’s testimony.

The most vexing question remaining is the early history of the design. Part of the answer lies in the identity of the designer, for which the lone published evidentiary information comes once again from René Dézavelle’s memoirs in 1974 : (9)

Il y a eu également un très beau paysage bleu, appelé « Lac de Côme ». Le dessinateur compositeur, successeur de M. Émile Nicolas (sic), avait été passer ses vacances au bord du lac de Côme et avait rapporté un très beau paysage – qui a été reproduit, sur de gros vases :

Au premier plan, une balustrade romantique, sur laquelle se trouvaient des pigeons blancs, et pour abriter cette balustrade, en premier plan, un énorme eucalyptus ; les pigeons blancs étaient gravés en creux, la balustrade et l’eucalyptus en relief ; derrière la balustrade, le lac bleu, dans le lointain les montagnes, bleues, dégradées.

Quelques vases ont été fabriqués pour la foire de Leipzig qui, avec la foire de Lyon, fournissait du travail pour toute l’année.

There is a lot to analyse in René Dézavelle’s testimony, where, as usual with him, the good information is mixed with the bad, or at least here with the approximate. It’s probably safe to assume that the detailed description of the landscape means that Dézavelle himself worked as a painter-decorator on at least one version of this series, which is why he would be still fond of remembering them more than 40 years later. The description of the design fits neatly with the B variant (27 cm) of the vase, but for a small detail : Dézavelle describes the pigeons as white and etched intaglio — meaning the vase was a two layers one, blue on white — but all the specimens I could find have the pigeons etched in cameo and therefore blue. This simply confirms that, as expected, there were coloured variants not represented (yet) in the available sample. Other details in this testimony are more important.

First, the composer-designer is not named, but designated as “the successor to Émile Nicolas”, which is an egregious double mistake — left uncorrected in the Glasfax Newsletter by the way — since the name of the main designer for glass (until his departure in September 1920) was Paul Nicolas, not Émile, his brother, a locally famous art critic and supporter of the École de Nancy.

As for the identity of this unnamed artist, Dézavelle is in fact alluding here to Auguste Herbst, even though Herbst was recruited by Émile Gallé back in 1898 and considered as an important part of the Gallé creative team from this early date — he was the second longest employed draughtsman after Hestaux since he left only in 1931, when he was dismissed with much of the workforce. So, Auguste Herbst cannot be considered Nicolas’ successor for he was active at the same time and then later. He was rather Hestaux’s successor, in the sense that it was Hestaux who was in charge of the draughtsmen team, and acting as a kind of artistic director. Paul Nicolas for his part was succeeded by Jean Rouppert in late 1919 or 1920 as the main composer for glass.

It’s quite striking, baffling even, that the name of Auguste Herbst is entirely missing from Dézavelle’s notes, especially since he was the Établissements Gallé artistic director during the whole time of Dézavelle’s employment there. All the other main actors of the artistic team are mentioned at least once, albeit with a faulty spelling : the previous main designers, Émile Nicolas and Louis Hestaux, as we’ve seen, but also the sculptor-modeller Paul Holderbach, and even Jean Rouppert (who is usually the great forgotten name of all the testimonies about the Établissements Gallé) (10). There is no indication that one should read this absence as anything else than a case of spotty memory. But it’s worth noting as an example of this testimony’s general lack of reliability and the need for a cautious approach when using it.

Auguste Herbst in Italy.

Second, the anecdotal origin of the design is given as a holiday trip. This is an important reminder that, as far as we know, all Gallé landscapes on glass (11) come from drawings and paintings made on the spot by the designers, during their vacations or on some excursions approved by the Gallé direction. It follows that by studying in detail the biography of these designers, their artwork outside the factory, like the paintings they exhibited in the salons, one could identify some Gallé landscapes whose original drawings are lost. The only identified major exception is possibly the Rio de Janeiro series, for there is no evidence (yet, to my knowledge) for some travel in South America by any of the Gallé artists. So pictures must have been used as the inspiration source for this one. But that’s not the case for the Lake of Como series, since additional information about it come from the Gallé family letters. They provide some crucial precisions on the chronology of this design, as well as some general historical context.

The July 1914 vacation

The only vacation in the Italian Alps on record by any Gallé collaborator is by Auguste Herbst, in July 1914, in quite peculiar circumstances that warrant a detailed account. That infamous summer, the beginning of the war took the Gallé principals by surprise as most of them were vacationing abroad, in Grindelwald, a village in the Bernese Alps (12), recovering from an already challenging spring: Henriette Gallé had died on the 22nd April and then in June, the main furnace had to be shut down, leaving the factory somewhat in uncertainty regarding that season’s scheduled production run (13). Paul Perdrizet, one of Henriette Gallé’s son-in-law and the new unofficial director of Établissements Gallé, rushed back to Nancy on the 28th July, where he made the arrangements for the closing of the factory, responding to the imminent war’s declaration. To his surprise, he found one of the three main Gallé artists unaccounted for and unheard of since the 11th July (14). The next day, a postcard from Herbst arrived avenue de la Garenne, informing the management of his trip in Italy. Apparently furious, Perdrizet wrote to his wife Lucile:

Enfin aujourd'hui on a reçu une carte postale de Herbst (adressée à Lang, depuis Colico ; seulement sa signature avec ces mots “Souvenirs“). Pour un hurluberlu, c'est un hurluberlu. Il est parti sans permission de moi ni de Lang, sans prévenir personne, pas même Holderbach — il a emporté la clef de son atelier. Et c'est le 30 que nous apprenons quelque chose de lui.15

Colico is a small resort on the north-western side of the lake of Como : this postcard is therefore the proof that the composer designer who went to vacation to Italy and brought back some landscape paintings of the lake was indeed Herbst.

By the time Lang and Perdrizet got these news, Auguste Herbst was certainly on his way back from Italy, since he arrived in Nancy on the 31st July and was met with a cold shoulder from his bosses (16) :

Herbst est revenu ce matin, on ne lui a rien dit, mais il a été tout de même reçu assez fraîchement, sans épanchement. Il dit que l'Alsace est remplie de préparatifs guerriers, comme ici.(17)

Quite naturally, Herbst had made his way back from Northern Italy through Germany, or more precisely through Alsace: he was from Strasbourg and probably went to visit his family one last time there before crossing back a border that would remain hermetically shut for the next foreseeable future. Like all the Gallé personnel, he was laid off on this same day, the factory ceasing all operations.

Still a German national, after working more than 15 years for Gallé in France, Auguste Herbst stayed first in Nancy and tried to make do with odd jobs. In October, with the factory still closed, he sent anyway some drawings to the Gallé direction for which he was paid 200 Fr as an advance (18), per Paul Perdrizet’s instructions, after he had reviewed them in his military encampment outside of Nancy!(19) There is no telling of course if the Lake of Como was among them, but it’s a remote possibility. There would be some irony if that these unauthorised vacations by Herbst in Italy resulted in the creation of what is surely regarded now — and was already in the 1920s, as per Dézavelle’s testimony — as one of the iconic designs of the Établissements Gallé.

Herbst made soon after his return to the Etablissements Gallé where a small team was preparing a limited reopening in January 1915. The objective was to fulfil some orders placed before the factory was closed. New designs were almost certainly impossible to create, at least with new glass shapes because of the unresolved issue with the main furnace : the composers and decorators had to make end with the existing stock of blanks (as are called blown glass pieces before the etching process). New designs, like the war themed ones, were adapted to previous shapes and colours, with a certain success, it must be said, and produced in limited numbers throughout 1915 and 1916.

Could it have been the case for a Lake of Como series? From a technical point of view, the Lake of Como belonged to the “blue landscape” series, that is a two or three layers vase (red brown on deep blue-violet, on the outside, frequently with an additional metallic yellow thin powder layer on the inside of the clear crystal base) (20), mainly mountain landscapes seemingly introduced during the early 1910s. So, there certainly were blue landscapes blanks still available in 1915 — some of them were used for war vases commemorating the war in the Vosges mountains (21) and of course the Ligne bleue des Vosges series acquired a renewed relevance. But, as we noted earlier, the Lake of Como design is almost unique in the very limited range of shapes it was applied to. Neither the classic ovoid shape of this series (coming in at least three sizes) nor the quite rare high shouldered baluster or urn form alternative had been used, at least before 1914, for a blue landscape — or for any other industrial design, for that matter. By contrast, these two shapes sometimes appear with different landscapes or even floral decors in the 1920s, as shown for instance in the 1927 sales catalogue.

Another argument against the introduction of the Lake of Como series during the war comes from the fact that Auguste Herbst was denounced as a German national and sent in June 1915 to a prisoner camp in Aveyron, where he was kept until November 1919 (22). While his presence might not have been absolutely necessary for this, it certainly was preferable that, as the original painter of the landscape, he would be the one in charge of its adaptation as a vase project and then the supervisor of the drawings made for the decorators. It follows that if these steps had not been already made at the latest by June 1915, and in fact, given what we’ve just seen of the events, by June 1914, the Lake of Como series could not have been created before late 1919 or early 1920.

Herbst’s watercolours from the SLAA salon in 1913

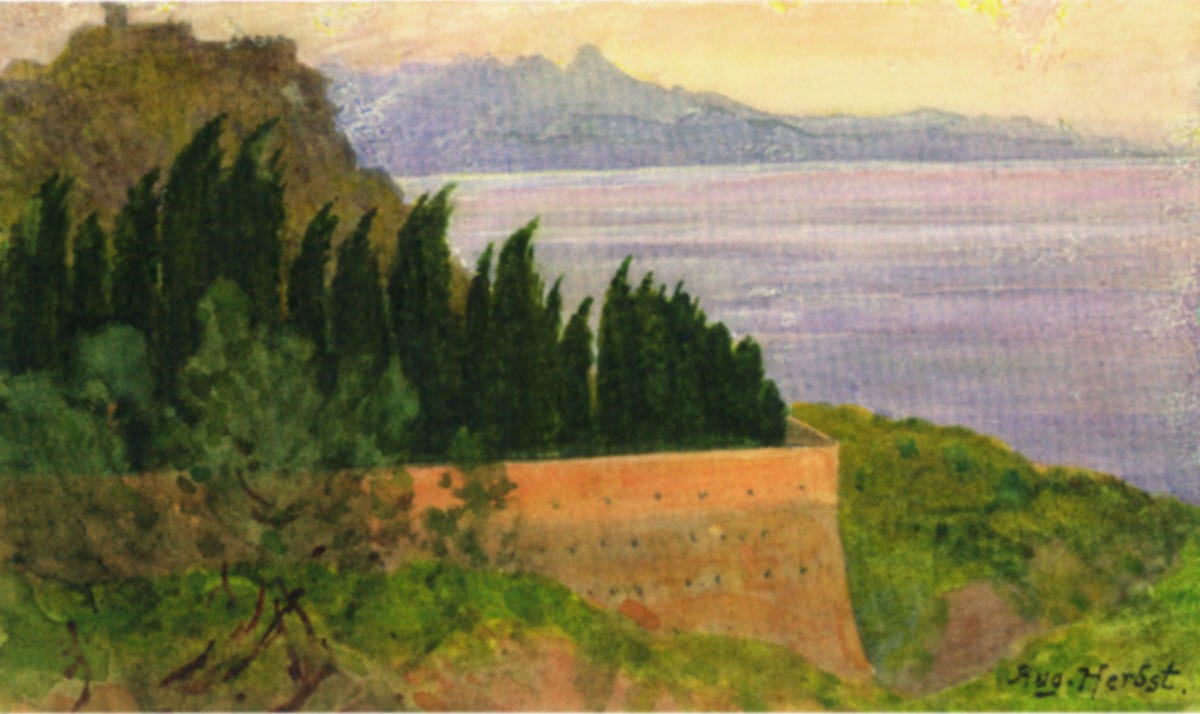

However, there had been still one window of opportunity for this creation before the war that we have yet to consider. The July 1914 trip to Colico was most probably not the first by Auguste Herbst on the Lake of Como’s shores. Like all the Gallé artists, Herbst was very regularly sending some personal art works to the salon of the Société lorraine des amis des arts (SLAA), an annual event taking place in the fall. As I have shown in a previous article regarding Louis Hestaux, these art works are a good indication of what the artists are working on in the Gallé studio at the time of the exhibition and many of them can be considered as some precursor works for some Gallé series. For the October-November 1913 salon, according to a review published in a local newspaper (23), Auguste Herbst had sent some much admired watercolours picturing the Lake of Como:

Quant à M. Auguste Herbst, ses grandes aquarelles du Lac de Côme (L’aquarelle est si difficile à traiter largement !) sont de pures merveilles. Tout au plus de l’une d’elles pourrait-on regretter une muraille verticale, à mon gré trop longue. Mais quelle qualité, pure et saine, d’atmosphère ! Quels harmonieux contrastes, quels chatoyants reflets ! Voilà des œuvres d’un sentiment bien personnel, qui eussent suffi, à elles seules, pour attirer le visiteur à l’hôtel de ville. (24)

Some of these watercolours from 1913 may have been published by Hervé Donat, a Strasbourg art dealer, in a booklet titled Auguste Herbst : un alsacien chez Émile Gallé, 1878-1961. One of them in particular, clearly picturing a mountain lake landscape, fits perfectly the critic’s description, with its long high retaining wall supporting a terrace filled with a row of cypresses (see the picture above). Without offering an exact copy of this landscape, the rare type D variant of the Lake of Como does have this kind of cypress filled high terrace overlooking the waters of the lake (see the picture below, on the left).

Does this mean that the Lake of Como vases could date from 1913 or even earlier? There is little doubt that these watercolours were the result of a previous visit by Herbst to the Northern Italian lake, most probably during his vacation the preceding summer. No earlier mention survives of such a trip or of other Italian paintings. Even so, a vase project following swiftly his return in Nancy, sometimes in the late summer of 1913, is perfectly possible, if not plausible. This would have been a limited series, to gauge the clients’ reaction. In this hypothesis, some Mk III marked vases would then date from late 1913 or early 1914.

But there are many reasons to doubt this scenario. First, Auguste Herbst was not in charge of the glass designs at that time : Paul Nicolas and Louis Hestaux were, and they are also known as the authors of the landscapes created during this late 1900’s-1910’s period. Would they and the Gallé management have allowed Herbst to outstep his role and to create his prestige landscape series with such a completely new subject? For what need? He had enough to do with the wood designs, it seemed. There’s a reason Perdrizet complained in his letter that Herbst had warned “not even Holderbach” of his absence : Paul Holderbach was the head of the Gallé woodworking and as such Herbst’s main collaborator.

Second, the way Herbst left surreptitiously, without telling anybody, to Italy the second time, in July 1914, suggests that the Gallé direction was not seeing any interest for the company in this vacation. That would not have been the case if a Lake of Como glass series had been under development from the previous year : he would have been encouraged to make more watercolours, to research the landscape’s potential for the vases. At the risk of over-interpreting this July 1914 incident, it looks like the sign that Herbst had not yet submitted a Lake of Como glass project, or, if he had, that it had been rejected. In this hypothesis, the second trip could have been the occasion to renew his material to make another attempt later.

Third, I have not found any tangible evidence whatsoever supporting such an early date for the creation of the Lake of Como design (yet ?) : nothing in the Charpentier notes (25) on the Daigueperce correspondance and account books, nothing in the few preserved letters from Herbst. The vase does not appear either on the photographs of the factory’s workshops from this period. These ex silentio arguments are weak, of course, but they do add up with the rest to cast quite a serious doubt on a 1913-1914 design hypothesis.

The Exposition Lorraine-Luxembourg in 1921 and the development of the Lake of Como series

After the war, as we already noted, everything changed : Auguste Herbst on his return in November 1919 became immediately the head of the Gallé studio, supervising all the designs. Jean Rouppert was appointed head designer for the glass, but he was inexperienced and worked first on developing the late Louis Hestaux’ designs, most certainly under Herbst’s supervision. The latter was therefore free to impose, at last, his project for a Lake of Como series.

Like in 1913, there is evidence that Herbst was painting at the time some Lake of Como landscapes, but this time the link with the Gallé glass is explicit. In October 1921, a special exhibition promoting the art from Lorraine was held in Luxembourg, L’exposition Lorraine-Luxembourg. The Établissements Gallé participated with a collection of glass pieces and cabinet furniture, while the main Gallé artists, including Louis Hestaux who had died two years before, were represented by some of their personal art works. This was therefore in part at least a retrospective. Here again, the watercolours of Auguste Herbst were particularly praised. The mention of a specific subject seems to indicate that his were recent works because his Château de Najac can only have been made during his captivity in Aveyron (26). The review in L’Est républicain singled out once again his painting of the Lake of Como:(27)

Auguste Herbst, dans ses aquarelles conçues d’après la vieille conception, est hanté par les orgies de couleur auxquelles se plaisaient les romantiques. Les reflets multicolores des verres précieux qu’il cisèle dans les ateliers Gallé semblent jouer encore dans son « Château de Najac », son « Soir au lac de Côme ». Les aquarelles de Louis Hestaux respirent le même romantisme.

The critic rightly underlined the strong existing link between Herbst’s glass projects for Gallé and his painting, but he understood the creative process backwards: the paintings were the basis for the projects in the Gallé studio and not the other way around. The title Herbst gave to his 1921 Lake of Come painting is of course significant : Soir au lac de Côme evokes the atmosphere of some darker variants of the Gallé landscape series, and sure enough, some auctioneers have actually taken to give this name to some specimens. That’s for instance the case of the type C, Mk IV signed vase – therefore congruent with a 1921 date – auctioned by Quittenbaum in May 2018 (28). The same auctioneer did also use the same name for one of the type B variants, Mk VIII signed this time – therefore a later production.

This testimony from the 1921 exhibition can be read as the confirmation that Auguste Herbst, the newly minted artistic director of the Établissements Gallé, was working at that time on developing the Lake of Como series, that he had personally designed and launched the year before.

Conclusion.

Going back to the account given by Dézavelle about the creation of this series, it certainly supports the idea that it was a post-WW1 design, for he attributes it (very approximately as we saw) to Paul Nicolas’ successor, implying thus that it was produced after Nicolas’ departure from Gallé in August 1919. But Dézavelle was a young apprentice at that time. He entered the Gallé factory workforce in August 1919 as a 14 years old, then left in 1925 for his military service in Strasbourg, before returning to the Établissements Gallé and staying until being laid off in 1930 (29). It would be unreasonable to rely solely on his teenager memory to date the beginning of the Lake of Como in 1919-1920.

But this testimony is supported by what we can reconstruct of Auguste Herbst’s work and life in the 1910’s-1920’s, from the few direct available evidence pertaining to this design. A pre-1914 creation looks possible from the perspective of Auguste Herbst’s travels in Italy. His role in the Etablissements Gallé and the tumultuous history of the 1914-1919 period preclude in reality such a creation. While he certainly made his first drawings in 1913-1914, he had to wait for the end of 1919, at the earliest, to see them put to glass. That’s anyway the working hypothesis until further documents emerge.

Appendix : a note on some fake Lake of Como vases.

As in the case of all the popular Gallé designs, the Lake of Como has attracted its share of forgers or blatant imitators. A Romanian firm (among several, it seems) is making a brisk business of unapologetically copying the Gallé industrial series, or rather of taking inspiration from them, for only the more gullible and unaware clients can fall for its products which bear but a passing resemblance (if even that) to the genuine items (30). These vases are more awkward hommages than real attempts at forgery as the example shown above illustrates, a pitiful fusion of the B and C landscapes originals. More importantly, they are not marketed as genuine Gallé. The copy of Émile Gallé’s portrait by Victor Prouvé in the background is also a “nice” touch.

Other vases are clear forgeries, like this specimen found on eBay, an attempt at copying the B landscape, and they probably could fool the uninformed. There was obviously more effort made into this one, but most of the details are wrong, from the shape (with a much too thick neck and rim) to the design (for instance, the castle in the background has little resemblance with the original) and the signature (a sorry copy of the Mk III).

© Samuel Provost, 19 February 2021

Bibliography

Dézavelle R. 1974, L’histoire des vases Gallé (The history of the Gallé vases), The Glasfax Newsletter, Montréal.

Donat H. 2015, Auguste Herbst : un alsacien chez Émile Gallé, 1878-1961, Galerie Hervé Donat, Strasbourg.

Provost S. 2018, « Une cristallerie d’art sous la menace du feu : les Établissements Gallé de 1914 à 1919 », in Thomas C. et Palaude S. (dir.), Composer avec l’ennemi en 14-18. La poursuite de l’activité industrielle en zones de guerre. Actes du colloque européen, Charleroi, 26-27 octobre 2017, Bruxelles, Académie royale de Belgique, p. 105‑118 [open access link].

Footnotes

See for instance François Le Tacon, L’Œuvre de verre d’Émile Gallé, Éditions Messène, Paris, 1998, p. 178. Most of the vases I could gather in my sample are also dated before 1914 by the auction houses or the dealers. ↩︎

See for instance Christie’s auction 5341, 20th Century Decorative Arts, 29 October 2008, lot 139, wrongly named ‘Lake Como’. ↩︎

Alastair Duncan, Georges De Bartha, Gallé Le verre, Bibliothèque des arts, 1984, pl. 204, p. 200. ↩︎

I did make an exception with auction.fr for which I used the premium version. The main other sites I used are the following : 1stdibs.com, chasenantiques.com, christies.com, invaluable.com, liveauctioneers.com, proantic.com quittenbaum.de, sothebys.com. ↩︎

The given size is an average, for there are slight variations (± 1 cm) from one specimen to the other that might come from the measurement made as much as from the making process. ↩︎

Some auction houses have taken to name one of the darker variants “Lac de Côme le soir”, but I do not know if they chose this name in full awareness of the design’s history. ↩︎

Dézavelle 1974, p. 27. ↩︎

Dézavelle 1974, p. 66. I have already explained here why it must be used with an healthy dose of caution. ↩︎

Dézavelle 1974, p. 66. ↩︎

Although his name does not appear in the Glasfax Newsletter but in some work notes from an interview given to Françoise-Thérèse Charpentier (private collection). ↩︎

Cabinet furniture is another matter, as I intend to explain in a future article. As for the glass, I am obviously not considering the big animals series (Elephants, Polar Bear, Condors, etc.) as landscapes. ↩︎

That means, by the way, that we should expect the main mountain summit of the area, the Wetterhorn, to feature on some Gallé mountain landscape vase. ↩︎

On the chronology of the event, see Provost S. 2018, « Une cristallerie d’art sous la menace du feu : les Établissements Gallé de 1914 à 1919 », in Thomas C. et Palaude S. (dir.), Composer avec l’ennemi en 14-18. La poursuite de l’activité industrielle en zones de guerre. Actes du colloque européen, Charleroi, 26-27 octobre 2017, Bruxelles, Académie royale de Belgique, p. 105‑118 [open access link]. ↩︎

Letter from Paul Perdrizet to Lucile Perdrizet, 29th July 1914 (family archives) : “Herbst n'est toujours pas revenu. Personne ne sait où il est. Il a disparu le 11 au soir. Il sera joliment peinard quand il réapparaîtra.” ↩︎

“Finally today we received a postcard from Herbst (addressed to Lang, from Colico; only his signature with these words "Memories"). For a nutcase, he’s a nutcase. He left without permission from me or Lang, without telling anyone, not even Holderbach - he took the key to his studio. And it is on the 30th that we learn something from him”: letter from Paul Perdrizet to Lucile Perdrizet, 30th July 1914 (Gallé family archives). ↩︎

As an aside, it’s worth noting that this same letter informs us that Louis Hestaux had just returned to Nancy from Chamonix in the French Alps. But he evidently had warned Lang if not Perdrizet. ↩︎

“Herbst came back this morning, nothing was said to him, but he was still received fairly fresh, without effusion. He says that Alsace is full of warlike preparations, as here“: letter from Paul Perdrizet to Lucile Perdrizet, 31st July 1914 (Gallé family archives). ↩︎

To put things in perspective, that was the gross price of a medium sized vase in 1914, or one month’s salary for the most experienced glassblowers and decorators. ↩︎

Letter from Paul Perdrizet to Elise Chalon, 26/10/1914 : “Je ne vous renverrai que demain les dessins de Herbst, le temps m'a manqué hier & ce matin (…) Faites à M. Herbst une avance de 200 F. Je crois que cela suffira pour le moment.” Perdrizet had enlisted in the infantry reserve as soon as he could, on the 3rd August 1914, for his age and his poor sight had prevented him to join the active army. ↩︎

See the detailed description by Dézavelle (1974, p. 18-20), with confirmation by Albert Daigueperce (Charpentier archives, regarding a 25 April 1918 letter from Perdrizet to Daigueperce). ↩︎

Valérie Thomas, “Produire pendant la première guerre. Les « vases de guerre » des Établissements Gallé”, Arts Nouveaux, 30, 2014, p. 34-39, esp. fig. 3, p. 37. ↩︎

The dates are given by an application Auguste Herbst made to the Commission Combarieu in January 1928 to receive some compensation for his time as a civil detainee during the war. He was denied on a technicality : Arch. Dép. 54, 4M218bis. ↩︎

Léon Malgras, “Salon de Nancy IX”, L’Est Républicain, 1913-11-10. I have to thank for this reference Julie Humbert, who completed a master’s degree in the Université de Lorrraine under my supervision on the subject of Auguste Herbst in 2017. ↩︎

“As for Mr. Auguste Herbst, his great watercolors of Lake Como (Watercolor is so difficult to treat widely!) are pure marvels. At most, one could regret from one of them a vertical wall, at my discretion too long. But what a pure and healthy quality of atmosphere! What harmonious contrasts, what shimmering reflections! These are works of a very personal feeling, which alone would have been enough to attract the visitor to the city hall. ↩︎

F.-Th. Charpentier did make a point of noting the appearance of new remarkable series : she probably would have considered the Lake of Como such a series. ↩︎

I will return to this hitherto practically unknown period of Herbst’s life in a future instalment of this newsletter. ↩︎

Jean de Crécy, “Lettre de Luxembourg. L’exposition d’art lorrain et la critique luxembourgeoise. Les arts décoratifs, les peintres et les sculpteurs”, L’Est Républicain, 1921-10-08. ↩︎

https://www.quittenbaum.de/ru/auktionen/----/138B/galle-etablissements-nancy-tall-le-lac-de-come-le-soir-vase-1920s--96351/↩︎

Dézavelle 1974, p. 35. ↩︎

For obvious reasons, I am not providing any link here. ↩︎

How to cite this article : Samuel Provost, “Le Lac de Côme series by Auguste Herbst for the Établissements Gallé”, Newsletter on Art Nouveau Craftwork & Industry, no 6, 19 February 2021 [link].

I will never own one of these vases, but how informative to learn about their origins. I appreciate the scholarship that went into this article and on a lesser note wonder if George and Amal Clooney who have a place on Lake Como have one.