Robert Chevalier and the Gallé family’s investment in Meisenthal glassworks

A new document as an introduction to one of Établissements Gallé’s administrators in the 1920s.

The destruction in 1936 of the better part of the Établissement Gallé archives remains a major obstacle in writing their history. For this reason, every bit of documentary evidence emerging from the Art market is worth a close examination. It happens once in a while that a Gallé piece, be it from ceramic, glass or wood, is sold with an actual proof of its original purchase, in the shape of an invoice, from the retailer or from the Gallé factory. These documents are especially important to establish or to confirm the period when a particular series was marketed1. The existence of an invoice is furthermore, the ultimate proof of a piece’s authenticity, from the owner’s as well as from the potential buyer’s perspective, a most significant point given the ever-present plague the fake Gallés bring in today’s market.

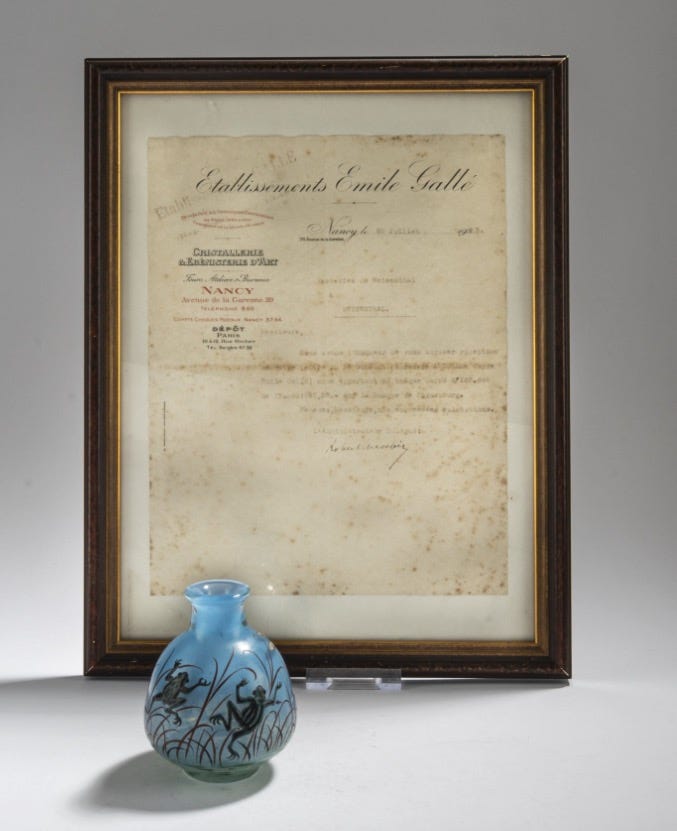

By association, to bundle some Établissements Gallé piece of paperwork with a Gallé glass might give the later an additional veneer of trust, even when the two are unrelated to one another. This may explain a very unusual lot sold last May by the Quittenbaum auction house: the main piece was a small Gallé clear blue coloured glass vase with an enamelled decor of two frogs chasing a dragonfly. This is a rare design, always featuring a Mk IV signature on the side: in my view, it belongs to the little known late Gallé enamel series, from the early 1920s, and not to the late 1880s, as it is often stated. I plan to extoll on this matter in a future article. As for now, our interest lays in the bundled document in the lot, initially described as an invoice from the Établissements Gallé from the 20th July 1925, but in reality a receipt for the annual dividend they received from the Meisenthal glassworks that year2. This is a new document that confirms known information, some of which remained unpublished until now.

The paper trail of a long-standing investment in Meisenthal

The receipt is written as a short type-scripted letter, on Établissements Gallé official letterhead paper, with a perfectly legible hand-scripted signature for Robert Chevalier. The letterhead is interesting since it states the name of the company as Établissements Émile Gallé, with an emphasis on recalling the founder’s identity. This detail is reinforced by the mention of Émile Gallé’s prizes in the 1889 and 1900 Expositions universelles in Paris, and by his status as a recipient of the Légion d’honneur high rank of commandeur. Some of these elements of the letterhead disappeared in the last version of the company’s official paper (in the early 1930s), namely Gallé’s first name and his Légion d’honneur. The change occurred in April 1925, when the company was incorporated under the name Établissements Gallé, rather than Établissements Émile Gallé, symbolically ushering it in a new era, in which it held a more distant relationship with its now long-disappeared founder. The July 1925 receipt is therefore using some leftover stationery from the previous period, when it was still a family business – nothing surprising in that.

The letter reads as follows:

Nancy, le 20 Juillet 1925

Verreries de Meisenthal

à Meisenthal

----

Messieurs,

Nous avons l’honneur de vous accuser réception de votre lettre du 16 courant (adressée à Madame Veuve Emile Gallé) nous apportant un chèque barré No 167.699 de francs:591,50 — sur la Banque de Strasbourg.

Recevez, Messieurs, nos empressées salutations.

L’Administrateur Délégué :

Robert Chevalier

The letter’s brevity looks at first as a major impediment to the understanding of the matter at hand. But its interpretation is straightforward, once a few basic facts are reckoned with. The Établissements Gallé are hereby acknowledging the reception of a letter, from the “Verreries de Meisenthal”, i.e., the Burgun, Schverer & Cie glasswork company, addressed to the widow of Emile Gallé, and containing a crossed cheque, drawn over an account in the Banque de Strasbourg, for the amount of Fr. 591.50.

This sum amounts to the retail price of a large Gallé vase at the time – so, it’s not nothing but not a fortune either. But it has nothing to do with a glass or furniture purchase, as it is clear from the plain letter format. The company would otherwise have used a void invoice with the listing of the paid for objects. Above all, one would struggle to understand why the Meisenthal glasswork would have bought something from Gallé. The money had therefore another purpose, that can be deduced from the fact that it was sent to “Veuve Emile Gallé”, a seemingly weird detail, considering that Henriette Gallé had died more than a decade ago, in April 1914. Surely, the Meisenthal direction knew that she was no longer the owner and manager of the Gallé company, so why send this payment in her name and not to her heirs and successors, the Gallé daughters and sons-in-law? The answer lies in the nature of the payout: its amount surely represents the annual dividends the Meisenthal company distributed to its share owners, among whom the Gallé family was still counted in July 1925 – but not for long.

The sharing and distribution agreement of the Gallé estate in 1914.

Émile Gallé had, despite his financial troubles at various points in his career, a diversified investment portfolio that his wife, Henriette Gallé, inherited in 1904. There’s no available list of these investments then, since he left everything to his wife — including some debts. But when she died in her turn, in 1914, a full account of the family financial situation was made3. The four Gallé sisters elected then to keep the business, run as a family association, under the unofficial direction of Paul Perdrizet (as a university professor he probably could not serve as a private company manager). But they divided among themselves the substantial portfolio of equities and bonds that Henriette Gallé had acquired. She had been able to do so with the proceedings of the soaring benefits coming from the streamlining of the glass production after 1904, under the advice of an uncle banker in Mulhouse and thanks to Paul Perdrizet, who had quickly taken a keen interest in the matter. As part of the inheritance settlement, the division was supervised by the family’s solicitor, who drew the corresponding act. The list shows, under the lot number 96, that the Gallé were still investors in the Société de la Verrerie de Meisenthal, a.k.a. the Burgun Schverer et Compagnie, to the tune of 14 shares. Each was worth 480 Marks (Meisenthal was then in German annexed territory) or 600 Francs for a total of Fr 8,400 – less than 2% of the entire Gallé portfolio’s value (Fr 442,605). An important note is that these were registered shares, rather than bearer shares: they were therefore under the name of Veuve Émile Gallé. The Gallé heirs kept the shares after 1914: the Fr 591.50 payment in 1925 was most likely the annual dividends they generated, a 7% return on investment, which seems about right. The cheque was sent for Émile Gallé’s widow because that’s who the shares were registered to.

Établissements Gallé and the Meisenthal glassworks in 1925: toward the end of a longstanding relationship.

The history of the relationship between the Gallé family and the Burgun, Schverer & Cie glasswork in Meisenthal is well known4. It began as early as the 1860s, when Charles Gallé, Émile Gallé’s father, began ordering blanks and finished enamelled glass pieces from the Meisenthal company, as he was doing from many other glassworks. A strong business relationship as well as real friendship developed between the director Nicolas Mathieu Burgun and Gallé, father and son. After Charles Gallé entrusted the family business to his son Émile Gallé, in 1867, Burgun, Schverer & Cie quickly became the exclusive provider for their glass product line. The French-Prussian war and the ensuing annexation of Alsace and East Lorraine, despite putting a border and additional administrative hassle in their exchanges, did not slow down the partnership, on the contrary: it became as much an artistic one as a commercial one, thanks to the talent of Désiré Christian, their leading enameller and other painter-decorators and glassblowers. Émile Gallé set up his own glass studio under Désiré Christian’s leadership, inside the Meisenthal glasswork, as soon as 1877 or 1878. The arrangement was detailed in a contact with Nicolas Mathieu Burgun and Émile Gallé in 1885, stipulating, among other things, Gallé’s exclusive ownership over the designs made for him in Meisenthal.

Symbolically, Émile Gallé took a financial stake in Burgun Schverer & Cie when, in 1889, Nicolas Mathieu Burgun changed the financial structure of his company, just before he died. His son Antoine Mathieu Burgun became the primary shareholder of the glassworks, with 60 of the 600 new shares (10%), while Émile Gallé bought 10 shares (1.6%).

The opening of the Gallé glassworks in Nancy, in 1894, changed forever the partnership with Meisenthal – from this date, Gallé made his own glass, while Antoine Mathieu Burgun decided to make Burgun Schverer & Cie an art-glass maker in its own right, with the Verrerie d’Art de Lorraine mark making its beginning in 1895 or 1896. Despite being now rivals rather than partners, Burgun Schverer & Cie and Gallé remained in good terms: Émile Gallé stayed on the Meisenthal company’s board and kept his shares. He even added four additional ones, in December 1900, when Antoine Mathieu Burgun made the company a limited partnership, still with 600 shares in total: Émile Gallé owned therefore 2.33% of the capital with his 14 shares, the same amount passed on by his widow to their heirs in 1914.

According to the Meisenthal register of shares transfer, the Gallé successors began selling theirs on the 12th September 19255, with the Chevalier presumably going first, since Claude Gallé kept hers until the 22nd September 19366, that is two months after the Établissements Gallé held their judicial sale to conclude their bankruptcy process. By that time, and probably all the way since Émile Gallé’s death, these shares did not represent anything more than an investment in the Gallé’s diversified portfolio. But, symbolically, the sale of most of these shares happening the same year when Établissements Gallé dropped their founder’s first name from their official designation reinforces the profound changes the company had been experiencing since the end of WW1.

Robert Chevalier (1880-1955) administrator of the Établissements Gallé

The only remaining question about the document is why it was signed by Robert Chevalier. He was, of course, perfectly suited to do so, as one of the three administrators of the Établissements Gallé in July 1925, along his two brothers-in-law Paul Perdrizet and Lucien Bourgogne, as we’ll see. He was also the only one on hand in Nancy at that date, since the Perdrizet were vacationing in Savoie, while the Bourgogne were probably in Paris. In Paul Perdrizet’s absence, Robert Chevalier was managing the company at an important period of transition, due to the recent incorporation of the Établissements Gallé, in April: on the 17th July, he wrote a letter from Épinal to his brother-in-law, then in Pralognan, asking for his advice on the particular wording of a circular to be sent out to customers, announcing these changes7.

But there is a reason to surmise that it was not only by happenstance that he specifically dictated (since it is typescript) and signed the receipt for the Meisenthal dividends. The Gallé family agreement on the inheritance in 1914 included a division of the financial portfolio in four equal shares – one for each daughter heir: the various equities and bonds were thus distributed according to their value among the four lots. The table summarising the distribution shows that most of the Burgun, Schverer & Cie shares (11 out of 14) were attributed to Geneviève Gallé-Chevalier, while Claude Gallé got the 3 remaining. Geneviève Gallé and her husband were therefore the recipients of the yearly dividend paid by the company. In that regard, it’s only logical that Robert Chevalier was the administrator signing the receipt.

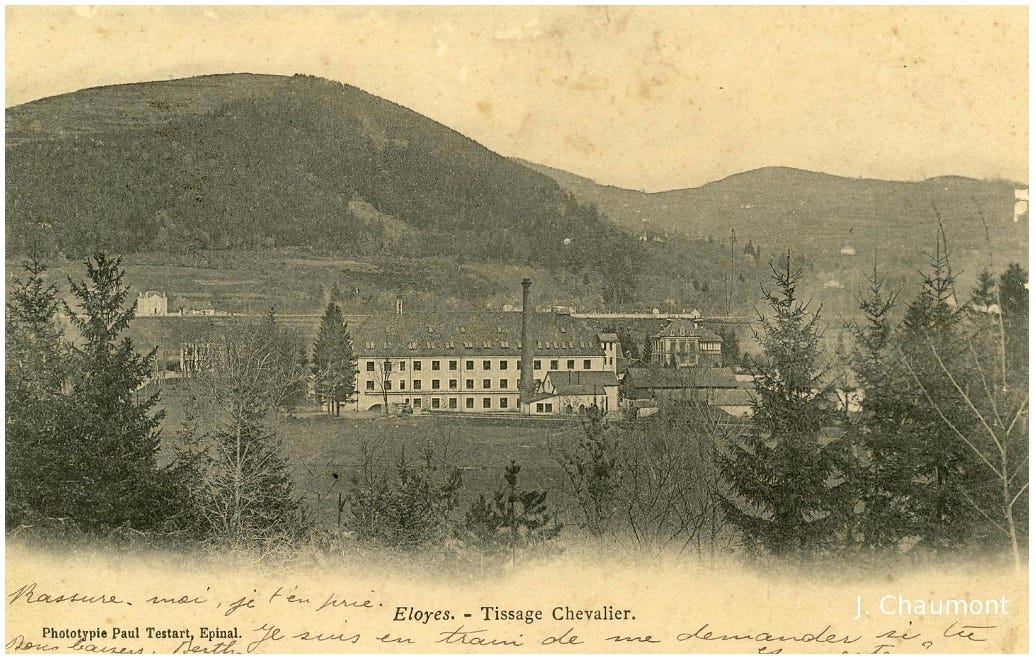

Not much is known about Robert Chevalier, even though he played a crucial role in the Établissements Gallé management during WW1 and afterward. He was a rich business owner from the Vosges with some roots in Alsace8: he inherited from his father Edmond the Établissements Chevalier, also known as the Tissage Chevalier, a cotton weaving mill in Eloyes, a village near Épinal, where the family had built a worker’s housing estate next to their factory. This Southern Vosges area had (it still has) a strong tradition in the textile industry, and the Chevalier prospered for a while. It was a relatively important company: when it was incorporated in February 1924, the Anciens Établissements Chevalier SA had 4.3 million Francs in capital, i.e., almost three times the size of the Établissements Gallé’s, but, like them, it was still a family business, with the Chevalier family holding most if not all the administrators positions9. The company had its social siege in Épinal, where most of the family seems to have had their residence.

How did Robert Chevalier meet the youngest of the Gallé daughters is unknown, but the Chevalier certainly had, like many prominent Vosges families, ties with Nancy, the major urban centre of Eastern France. One hint in this regard comes perhaps from the marriage’s record in the civil registry. The marriage was celebrated in the temple of Nancy, on the 7th July 1910, with the bride’s brothers-in-law, Paul Perdrizet and Lucien Bourgogne, as her witnesses, while the groom was assisted by his brother—in-law, Georges Hatt (an administrator of the Tissage Chevalier) and a cousin, Théodore Weiss10. The Weiss were a prominent family of medical doctors in Nancy, old friends of Émile and Henriette Gallé, mentioned in their correspondence11. Later, their son, Théodore Weiss, a professor in pathology in the Faculty of Medicine12, was the personal doctor of Henriette Gallé13. It is therefore quite possible Robert Chevalier met the Gallé through the Weiss intermediary. At the very least, they frequented the same social circles.

The family business kept Robert Chevalier busy in Épinal, and there is no indication that he played any role in the Établissements Gallé management before 1914, contrary to his brother-in-law, Paul Perdrizet, who lived with his wife in the Gallé family house and became Henriette Gallé’s trusted right arm around 1910-1912. But the situation changed quickly, first with Henriette Gallé’s death in April 1914 and then with Paul Perdrizet’s enlistment in the army in August 1914. If Perdrizet was able in the first year of WW1, from his various stations around Nancy, to keep an eye on the factory – which was mostly closed –, he was transferred to Paris in October 1915 and had then to find help for his sister-in-law, Claude Gallé, to manage the reopened family business. Robert Chevalier stepped in and travelled many times from Épinal to Nancy, to consult the factory’s director, Émile Lang, and to serve as the family’s representative. Paul Perdrizet was still the main decision maker, but Robert Chevalier’s influence was real. After the war concluded, he kept this role and he regularly stood in for Paul Perdrizet, when the university professor was taken by his academic and scientific activities, in particular with long travels abroad all over Europe and the Near East — or simply when he took vacations as we’ve seen in July 1925. The Perdrizet-Gallé and the Chevalier-Gallé were close enough to take vacations together in Brittany during the late 1920s-early 1930s.

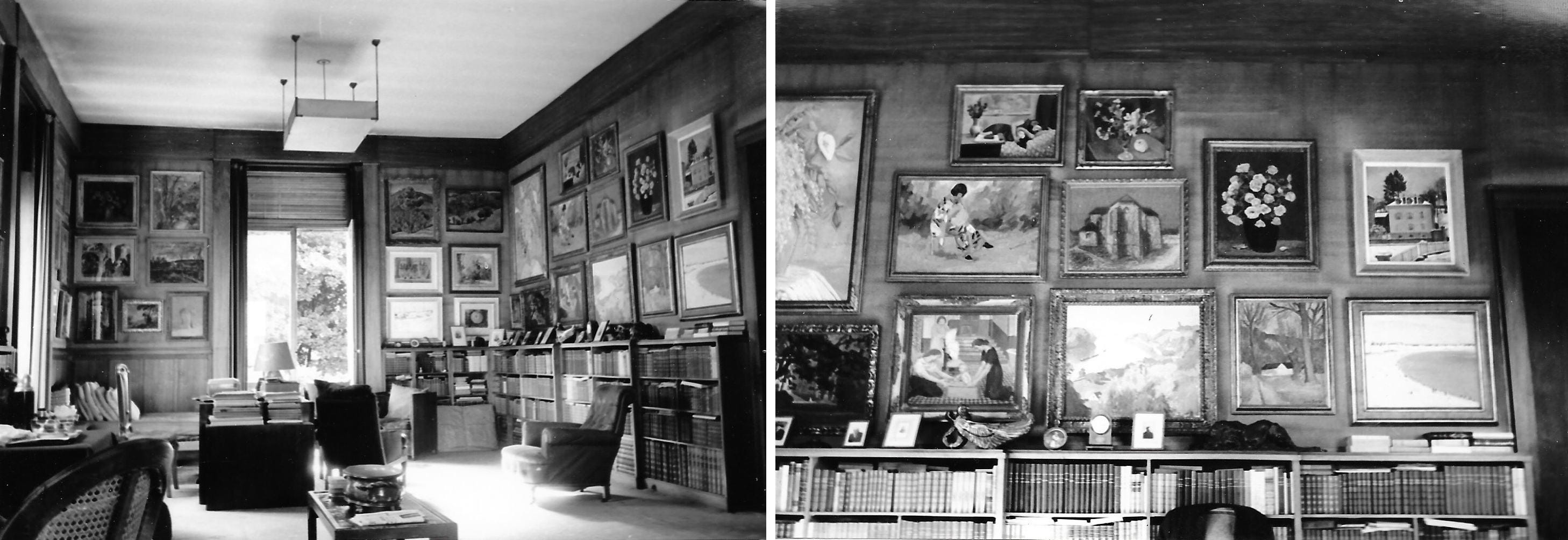

The Chevalier couple were very much involved in the cultural and artistic scene in Épinal, as benefactors and patrons of various institutions. For instance, Robert Chevalier was the secretary of the Association des concerts classiques14, and he was also a patron of the local theatre. More open-minded than his brother-in-law Paul Perdrizet, it seems, when it came to contemporary art, Robert Chevalier was a collector of modern paintings, and Paul Perdrizet introduced him, as early as December 1910, to his friend, the art critic and librarian René-Jean, then working for the great Parisian collector Jacques Doucet15. This was the beginning of a long-term relationship between Robert Chevalier and René-Jean, who served as an informal adviser to the industrialist for his art acquisitions, introducing him to renowned painters of the time like Raoul Dufy or André Dunoyer de Segonzac16. In 1927, Robert Chevalier enlisted the service of the up-and-coming young designer Jean-Michel Frank, who decorated entirely the Chevalier couple’s new villa in Épinal, in Art Déco style17, with some help from Geneviève Gallé’s godson, Jean Prouvé, himself on the eve of an illustrious career as a designer. This shows – and the subject will be worth returning to in a future article – that Robert Chevalier was finely tuned to the artistic movement of his time and that he could have played a significant part in Établissements Gallé’s (very modest) turn to Art Deco.

In the late 1930s, the Établissements Chevalier were bankrupted, like many family businesses, in the economic crisis. Of course, the Établissements Gallé were also closing around the same time. Robert Chevalier, according to the family tradition, became an insurance broker, perhaps for the Abeille Vie company. This was a domain in which he had demonstrated some expertise earlier on, advising the Gallé for all insurance matters. He died on the 3rd June 1955, without direct heir, his couple being childless. His widow, Geneviève, then chose to return to Nancy, to live with her two sisters in the Gallé family house, where she died on the 8th September 1966.18

© Samuel Provost, 14 August 2023.

Bibliography

Fleck Y. 2005, “Emile Gallé, verrier à Meisenthal”, in Le Tacon F. (ed.), Actes du colloque organisé par l’Académie de Stanislas, 28/29 septembre 2004, En hommage à Émile Gallé, Annales de l’Est 2005, p. 141-152.

Le Tacon F., Franckhauser P. and Fleck, Y. 1999, Meisenthal Berceau du verre Art Nouveau, exhibition catalogue, Musée du verre et du cristal, Meisenthal, 1999.

Traub J. 1978, The Glass of Désiré Christian, Ghost of Gallé, The Art Glass Exchange, Chicago, 1978.

Footnotes

See for instance my essay on the Gallé signatures in the 1920s for such an instance, in the section about the date of the Mk VI signature.

Full disclosure: I made this remark to Quittenbaum who confirmed the reading and changed accordingly its listing and its description of the paperwork – as well as the unrelated date of the vase. I thank them for sending me an additional picture and for allowing me to publish it.

Partage des successions de Mr et Mad. Gallé, Me Droit, notaire, 20 June 1914, Archives départementales de Meurthe-et-Moselle (70 E 141).

See Traub 1978, with some additions in Le Tacon, Franckhauser and Fleck 1999, p. 14-30.

Fleck 2005, p. 152.

Le Tacon, Franckhauser and Fleck 1999, p. 27.

Letter from Robert Chevalier to Paul Perdrizet, 17th July 1925, Archives Paul Perdrizet, Université de Lorraine (PP 112).

This is according to Paul Perdrizet: letter from Paul Perdrizet to René-Jean, 13 April 1910, Correspondance René-Jean, INHA, Paris, ARJ 144-3-662.

“Anciens Etablissements Ed. Chevalier”, La Journée Industrielle, 29 February 1924, p. 2.

Le Mémorial des Vosges, 12 July 1910. See also the recording of the marriage in the État-civil, 1910, nr 620.

Letter from Henriette Gallé to Émile Gallé, 27 July 1885, in Gallé É., Gallé H., Amphoux J. and Thiébaut Ph. (ed.) 2014, Correspondance 1875-1904, Genève, La Bibliothèque des arts, p. 73-74.

On his career, see Rapport annuel du Conseil de l’Université et comptes rendus des facultés, année scolaire 1921-1922, Nancy, 1923, p. 96-97.

As such, he was sent a copy of the commemorative brochure the Gallé edited after Émile Gallé’s death: letter from Paul Perdrizet to Claude Gallé, 26 September 1916 (Gallé family archives).

Le Télégramme des Vosges, 6 October 1926, p. 2.

Letter from Paul Perdrizet to René-Jean, 10 December 1910, Correspondance René-Jean, INHA, Paris, ARJ 144-3-705.

The René-Jean archives keep five letters from Robert Chevalier documenting these matters: Autographes René-Jean, INHA, Paris, 188-35.

Pierre-Emmanuel MARTIN-VIVIER, Jean-Michel Frank: l'étrange luxe du rien, Paris, Éditions Norma, 2006, p. 118 et 122. Some furniture modelled after the villa’s regularly appear on the market: for instance a pair of armchairs and a canapé in 2013.

My warmest thanks go to Jacqueline Amphoux for all the family information about Robert Chevalier.

How to cite this article : Samuel Provost, “Robert Chevalier and the Gallé family’s investment in Meisenthal glassworks. A new document as an introduction to one of Établissements Gallé’s administrators in the 1920s, Newsletter on Art Nouveau Craftwork & Industry, no 24, 14 August 2023 [link].