The Metamorphosis of Daphne : on Méliodon’s and Gallé’s lamps.

A preliminary research on a little known sculptor’s contributions in the Art Nouveau applied arts.

The Méliodon lamps.

Last month, on the 10th July, the Japanese auctions house Est-Ouest sold a lamp with an attribution to Émile Gallé and M. Meliodon (lot #47). The bronze lamp’s pedestal represents a woman whose body merges with a plant stem in a languid pose, her head is thrown back and her arms outstretched along a gnarled stem that describes an oval above her, the top of which supports the attachment of the glass bulb cover. This lamp shade is shaped as a large flowerhead with distinct petals’ tips. It features a two-layers, rose and green, acid etched pattern of umbels (?), and it is signed Gallé in a wavy, but simple script etched in cameo near the lower edge. The lamp is 53.8 cm high for 40.6 cm in diameter.

While lacking a signature or a foundry’s stamp on the base, the lamp is rightly attributed to “M. Méliodon”, for this is one of many specimens of this design to be auctioned off these last decades. But despite its relative availability, nothing is known about the creation of this model and basic facts like the authorship itself or its date remain in doubt1. This is an attempt to shed some light on this little mystery, and particularly an assessment of Gallé’s involvement in the matter.

The metamorphosis of the nymph Daphne.

The object belongs to the very popular theme of the Art Nouveau “flower woman lamp” that associates the representation of a naked or scantily clad woman in a languid or pensive pose with a flower shaped shade or bulb. It seems like every major modeller, glassmaker or artistic foundry had one model at least. In her academic study on Daum light fixtures, Justine Posalski has provided a useful répertoire of ten such different lamps fitted with shades or light bulb covers by Daum, spanning the 1910s and 1920s and coming from an international casting of sculptors modellers2. One of these is none other than the Méliodon lamp under discussion here.

The particular variant of the flower woman used by Méliodon can be more accurately described as the metamorphosis of a woman into a flower tree. The merging of the woman’s body with a tree trunk, rather than a plant stem, evokes the myth of the nymph Daphne, whom Zeus changes into a bay laurel tree in trying to help her to escape from the desires of Apollo. This is one of the most famous tales of Ovid’s Metamorphoses (Book I) and therefore a common theme in painting and sculpture: see for instance Antoine Bourdelle’s Daphné devient laurier, a bronze from 1910, or again an Art Nouveau bronze lamp signed E. Thomasson, and frequently fitted with a Tiffany style shade, that illustrates the same theme in the light fixture category.

In the case of the Méliodon lamp, the identification of this mythological theme looks all but certain when one considers a more explicit variant of this design: Millon sold in 2020 a two bulbs version of the lamp. It has the same general basic structure, with the difference that the oval overarching vegetal structure is almost horizontal and that its extremities support two lamp sockets. More crucially, the vegetal stem bears what looks like bay laurel (a.k.a. Apollo’s laurel) leaves. In this context, to push further the symbolic interpretation of the design, the light bulb under which Daphne languishes could very well represent the Sun God Apollo, from whom she’s trying to escape.

A common design without a standard glass shade.

A nice verification of this hypothesis could have resided, perhaps, in the decorative pattern of the glass part of this lamp. A bay laurel’s flower pattern would have been the logical choice, but such is not the case: the Est-Ouest 2021 specimen sports an umbelliferae decor. This does not invalidate the symbolic interpretation of the lamp, though because this particular shade is one among many ones this lamp design comes with. A survey across auctions sites reveals at least twelve specimens of the lamp sold in the last two decades, among which four had a Gallé signed glass shade, one Schneider, one Daum, and six had none (or a modern textile one). The lamps present various kind of patina or finishes. It cannot be excluded that some of them are modern copies.

That the majority of the lamps do not have a shade has two major implications. First, it means that either the original bulb cover was quite fragile, since it did not survive, or that there was none provided. And here, the symbol of the Apollo Sun God that would be the bulb, in our interpretation of this design, might reinforce this hypothesis: leaving the electrical bulb naked rather than concealed by a cover would manifest more clearly the symbolism. As we will see below, this is probably the right solution, considering the similar lamps made by the Guinier bronze foundry. Second, it also increases the probability that the six remaining glass shades are all second hand ones rather than the original glass part of the lamps. Either way, it looks quite certain that this lamp was not an exclusive design for a particular glassmaker.

For what it’s worth (not much!), the four Gallé shades look genuine. Their making can be dated ca. 1902-1903. The umbel model reused on the Est-Ouest auctions Méliodon lamp, for instance, was part of the Ecole de Nancy exhibition in the Pavillon de Marsan, in 1903: it features on the Guérinet album from the exhibition. It was then shown as a ceiling fixture, but it could also be affixed to a wrought-iron foot and used as a table lamp, as the slightly different specimens kept in the Musée de l’École de Nancy can attest3.

The M Méliodon signature.

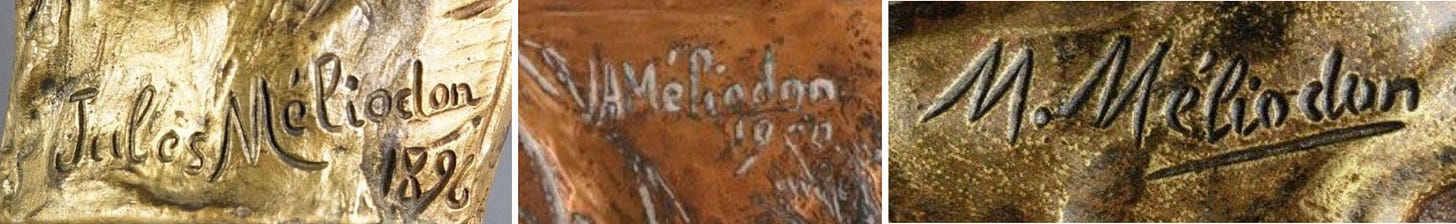

The lamps always bear the same signature, “M Méliodon”, and often a stamp from the Guinier’s artistic foundry in Paris. While the latter is a well-known maker of artistic lighting fixtures in the early 20th c. (see below), the former’s identification poses a challenge. Méliodon is not a common name and the only one known as a modeller is Jules André Méliodon, an artist born in 1867 and active in Paris from 1894 to ca. 1910 — he then emigrated to the USA. We’ll go over his biography in details but suffice it to say, for now, that obviously his initials do not match the signature, and that there is no ready explanation for it.

For all we know, Jules André Méliodon always signed his creations, as he was particularly protective of his copyright. A series of vases he created in 1896, which were edited by the Louchet foundry (so, not Guinier), features his signature as “Jules Méliodon”, with the date. Some later works, from 1900 at least, have his initials before the name, as in “J. A. Méliodon”.

Lacking another credible candidate, most of the art experts have conflated the signatures and assumed more or less openly that they were from the same artist, Jules André Méliodon. Occasionally, they finesse this by keeping the M. Méliodon combined initial and name, but by adding Jules André’s 1867 birthdate. From a stylistic and thematic point of view, this attribution makes perfect sense. Jules André Méliodon signed artworks often borrow from the Greek mythology and many feature some nymphs, like the so-called Temptation of the Faun (1896), where a satyr whispers to the ears of a nymph languishing on a swing. The nymph’s posture, with her outstretched arms and thrown back head, is even reminiscent of Daphne’s in the M. Mélodion’s lamp.

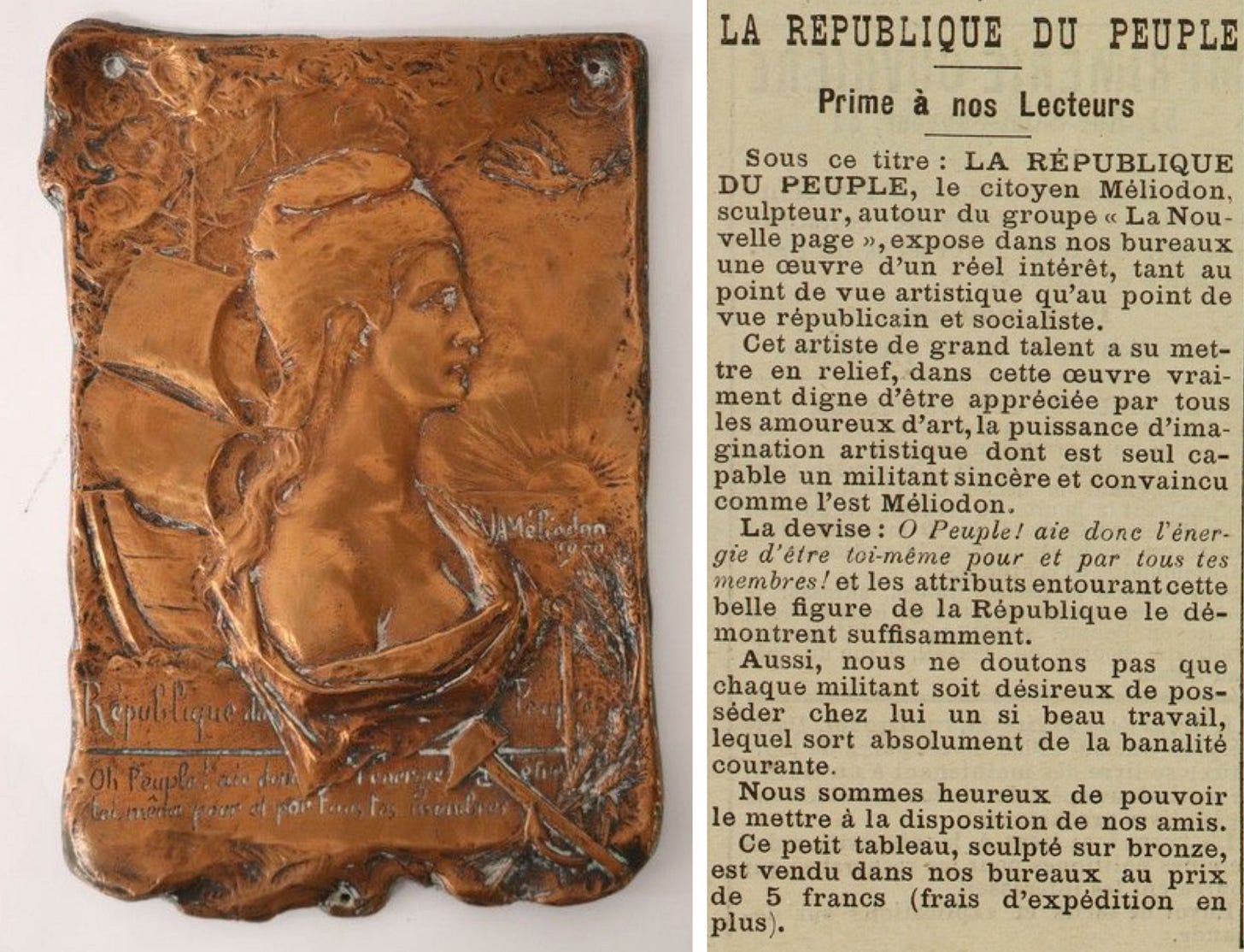

So, “M. Méliodon” could be a particular signature of Jules André Méliodon, despite the lack of explanation for this M initial. I would venture one highly speculative theory though, stemming from the fact that on some of his “J. A. Méliodon” signatures, the JA initials are so close to one another that they could perhaps be read as a M, like on his La République du Peuple (1900). Could the workers from Guinier have misread the name on the design and produce this faulty signature? Assuming many copies of the lamp could have been made after Méliodon’s final departure to the USA, he was not here anymore to correct the mistake. Another speculative explanation would be that the mistake was intentional, if Guinier “borrowed” the design and made this slight change to protect himself from copyright infringement. Still other theories are possible.

An alternative for the “M Méliodon” signature? Marie Méliodon, a little known painter on glass.

The “M Méliodon” signature is all the more troubling because there exists another contemporary artist whose first name would match this M initial letter: Marie Méliodon is an even less documented artist than her sculptor homonym. She was presumably a painter on glass, specialising on oriental styled enamels. At least, that’s how her artwork is described in the rare available reviews. She attained enough renown to be included in the Exposition de la verrerie et de la cristallerie artistique organised by the Musée Galliera in 1910, where her artworks were exhibited among those of other better known enamellists such as Alphonse Giboin and Jean-Désiré Ringel d’Illzach4. More details are available in an older publication5, describing in some length her offering to the Société nationale des Beaux-Arts in 1902:

Parmi les œuvres d’art présentées à la Société nationale des Beaux-Arts, sous le no 169, Mlle Marie Méliodon expose six vases de cristal émaillé, traités dans le goût oriental. Ces belles verreries se recommandent par la pureté de leur dessin, la richesse de leur coloris et l’heureuse disposition d’une gamme de teintes qui les font ressembler aux anciennes pièces émaillées des ateliers de Chiraz et de Téhéran (…)

Why did the writer, Paul Barret, choose to highlight, among the rich annual catalogue of works presented to the SNBA, this little known artist’s painted glass pieces, and them only, in this short note for a general interest journal? The answer lies in her address (6, Alboni street in Paris’ affluent 16th arrondissement), as given by the official catalogue of the 1902 Salon6. This was the home address of the most famous Méliodon at that time, Philibert Méliodon, a prominent banker, the general secretary of the Crédit Foncier de France7. He had a daughter called Marie, born in 18788, who is therefore the enamellist painter of the 1902 Salon. It was not out of character for the daughter of a banker to dabble in the arts. Without being unduly unfair, her belonging to the Parisian high society probably explained the special interest Le Carnet historique et littéraire took in her one and only showing at the Salon.

Whatever the case, Marie Méliodon’s career as an artist remains obscure. She is absent from all the glass related dictionaries (like Hartmann’s) and reference books, as are her artworks from the public collections, as far as I could determine. She probably worked from blanks she bought from a glasshouse in the Paris area, like Legras, as one of many such painter-decorators in this period, and there is no telling if she ever sold some of her art. It seems far-fetched, to say the least, that she could have been the sculptor of the “M Méliodon” signed lamp. But that hypothesis had to be explored, since there is no direct evidence either linking this design with Jules-André Méliodon.

Jules-André Méliodon, a short biography.

Jules-André Méliodon is then almost certain to be the creator of this design. He is known as a competent but second order French sculptor, who, despite some modest early success in the 1900s, failed to make a career in Paris and chose to emigrate in the USA, where he apparently spent the rest of his life. He is the subject of a small article in the Bénézit Dictionary of Artists9, which names him as student of the sculptors A. Falguière, E. Fremiet, Barrou and Messagé in Paris, and as a member of the Société des Artistes Français and the Société des Professeurs Français en Amérique. His only mentioned artwork is his portrait of the explorer Lesueur. Various other specialised biographical dictionaries provide the same basic outline, with few additional facts10. It seems therefore a good occasion to try building up the skeletal résumé of this artist with new information culled from public archives and published contemporary sources. One caveat is that his name was sometimes misspelled “Mélodion”, which hinders somewhat the biographical research.

Jules-André Méliodon was born on the 1st June 1867, the son of Antoine Méliodon and Françoise Van Cutsem, haberdashers in the Faubourg Saint-Antoine in Paris, a neighbourhood he continuously lived in most of his early life in Paris11. He was registered for his military service in 1887 with the recruit number 1987, but obtained a two-year postponement, before filling out his duty in the 79th Infantry Regiment from November 1890 to November 189112. He was at the time living 58 rue de Falguière in the 12th Arrondissement, and gave his professional occupation as a “musician”. Furthermore, he took up the study of the fine arts at the Ecole nationale supérieure des beaux-arts in Paris, in the mid-1890s, and became a student of some of the most famous sculptors at the time. He is then quoted in 1899 as a sculptor himself and as a professor in the school of the rue de Turenne in Paris13. He was successful enough to be distinguished in 1904 as an officier de l’Instruction publique, a minor honorific distinction awarded to civil servants in the education and culture sector.

There are few additional biographical facts known about him, except that on the 3rd February 1904 he married a young woman, Louise Hugot, in her village, Saint-Gobain (Aisne). His profession is then given as a statuary artist and his address as 68, boulevard Diderot, still in Paris’ 12th district.

Jules André Méliodon regularly exhibited sculpture artworks at the Salons in the 1890s and 1900s, like for the Société nationale des beaux-arts in 1907 (Champ-de-Mars), and for the Salon des artistes français, beginning in 189414, and several times after that until at least 190815 (Grand Palais), where he received several prizes, notably for his portrait-medallions in bronze. He is awarded an honourable mention for his sculpted group La Source in the 1902 Salon des Artistes français, for instance16.

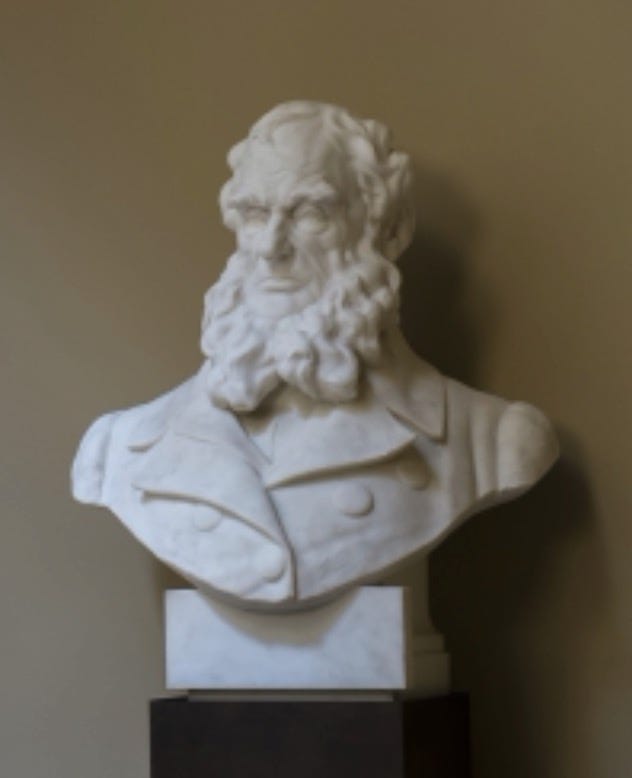

As it has already been noted, his most famous work is a marble bust of the explorer and naturalist Charles Alexandre Lesueur (1778-1846), a State commission to the artist in 190417. The bust was exhibited in the Salon de peinture et de sculpture of 1905, and it is displayed today in the Grande Galerie de l’évolution, at the Museum national d’histoire naturelle in Paris18. He was also one of the sculptors to work on the decor of the new Sorbonne university building.

Jules André Méliodon, socialist militant.

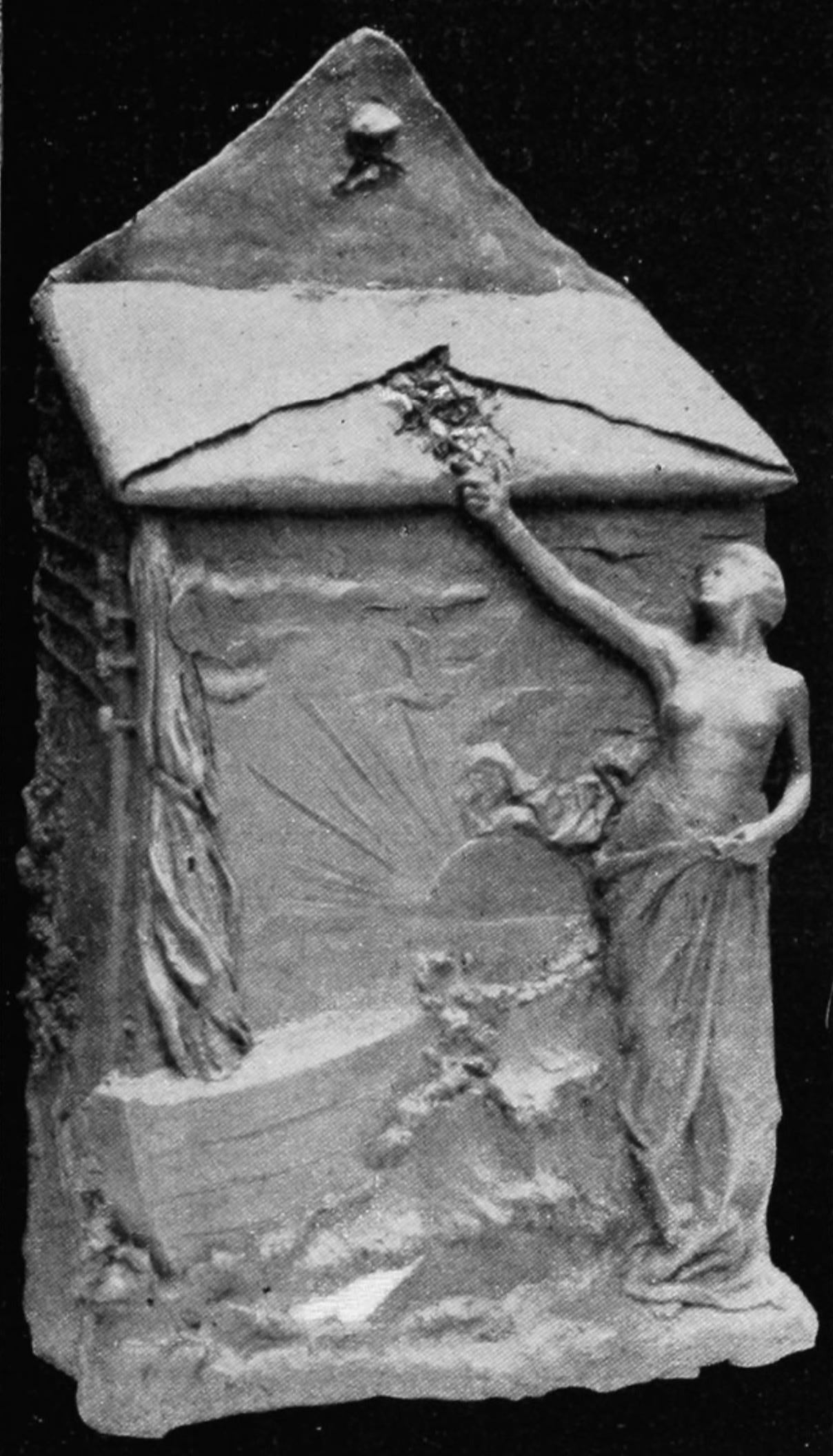

Like many of his peers, Jules-André Méliodon was fully engaged in the political controversies of his time, and he did not hide his affinities with the socialist left, on the contrary. A Free Mason19, he was also a Dreyfusard, having signed one of the many public petitions related to the Dreyfus Affair in late 189820. Anticlericalism was probably one of his main motivations, if one can judge from some of his artworks’ themes. One of his project, known from a plaster model of the monument, is dated from 1899 and eloquently titled: La Nouvelle Page: la Pensée libre écrase la superstition et la Force brutale, protège l’Art et la Science et impose la Paix au monde (The New Page: Free Thought crushes superstition and brute force, protects Art and Science and imposes Peace on the world21). Residents of the 11th and 12th arrondissement in Paris sent a petition to the city council in 1900, for Méliodon to be lent a workshop big enough to accommodate this large statuary group22 — but it failed to garner sufficient interest and financial support. A one meter high model of this statuary group was exhibited in the public library of the Université Populaire du faubourg Saint-Antoine, one of the numerous educational and social projects that flowered at the time during the Dreyfus Affair. On this occasion, the review Les Questions actuelles describes Méliodon as “a worker-artist, a sculptor who makes a living with industrial work all day long and then, in the evening, dabbles in art”23. This characterisation makes Méliodon one of the ideal prototypes of the founders and participants of such highly political educational projects24. But it also underlines his financial difficulties, his inability to make a living as a statuary artist at the time.

Another of his artworks underlines in a striking fashion both his socialist ideology and his efforts to raise money. La République du Peuple is an allegorical portrait of the People’s Republic, dated from 1900, sculpted in low relief on a bronze plaque. It bears the following quotation, “Oh Peuple! Aie donc l’énergie d’être toi-même pour et par tous tes membres”. The quotation seems to be from Méliodon himself, and it is a direct call to action from the people, in a reference to some socialist ideas, as they were eloquently expressed, for instance, by Jean Jaurès in a speech to the Chambre des députés in January 1898, in the context of the Dreyfus Affair25. Méliodon stroke a deal with the socialist newspaper Le Cri du Peuple to sell copies of his relief: in its 20th October 1901 issue26, the newspaper advertised the artwork as having “a real interest, from the artistic as well as from the republican and socialist point of view (…) a real fine work which is absolutely out of the ordinary”. The article praised “the citizen Méliodon” as “a sincere and committed activist” and encouraged its readers, who would be “undoubtedly eager to have such a beautiful work in [their] home”, to order a copy of the artwork from the newspaper’s office, for the price of Fr. 5. Socialism and marketing were not averse to each other after all, it seemed. It’s difficult to gauge the success of such an unusual arrangement, but at least one of these plaques recently resurfaced in an auction sale (see above)27.

Méliodon’s financial trouble is hinted at in an archival file from the Direction des Beaux-Arts et de l’Architecture, which deals with his petition for help in 190328. The State commission he received for Lesueur’s bust the next year was perhaps intended as a relief of a sort, but it was clearly not enough.

Jules André Méliodon in the USA.

Probably still struggling to make end meets in Paris, he must have decided to try his luck in America, ca. 1910 at the latest. While he apparently still lived in Paris in 190729, he was advertising as a French Modeller for making “figures, ornaments, flowers” in the USA as early as 1904, in trade reviews, with an address in New York30. One of his artworks, Gethsemane. Statue of Christ kneeling on rocks (quite a subject for a free thinker!), is registered for the first time in a US catalogue of copyrights with the date 24 September 191031. He therefore must have emigrated to the USA in between.

What happened to him after that is not really our concern here, since he apparently cut off all links with the Parisian artistic milieu32. He went on to work for the University of Pennsylvania as a modelling instructor (hence his membership to the association of French professors in America) and he was later (in 1933) commissioned an important public work by the Philadelphia’s Board of Education, a series of 24 sculpted figures and groups to adorn their monumental new building33. What could have been the pinnacle of his career did not end well, because of a dispute over the poor execution of his project which resulted in a trial and in a landmark decision in copyright law, Méliodon v. Philadelphia School District. Méliodon sued the district, arguing that the changes made to his models were so great that they damaged his artistic reputation, and he lost. He died a few years later, at an unknown date, after 1940.

Jules André Méliodon and the applied arts.

Méliodon was not alone among the sculptor-modellers to have difficulties finding lucrative work in France, at a time, the early 1900s, when the golden age of the State commissions to the artists had come to an end. And, like his peers, he tried to supplement his income by diversifying his work and using his talent as a modeler in the applied arts. He had some kind of critical success in this area too, since his name features in the prize lists of some design competitions.

In 1900, his letterbox project receives the fourth prize in the Concours de sculpture d’ornement spécial aux métaux, organised by the Union des fabricants de bronze34. In November 1902, he presented a wooden sculpted street sign, for a furniture manufacturer, in a shop sign competition held in the Paris Hôtel de Ville35. These efforts confirm, as do some Méliodon’s signed minor objects (bookends and such) seen in the auctions sales nowadays, that the modeler was well involved in the applied arts: the design of a table lamp was therefore very much in his capacities.

The Méliodon lamps and Gallé.

Setting aside the fact that lamps fitted with a Gallé shade do not remotely constitute the majority of the available specimens for this Méliodon design, it still is necessary to examine whether Émile Gallé or later his heirs might have willingly provided these glass pieces to adorn the sculpted mount.

Édouard Guinier’s bronze foundry.

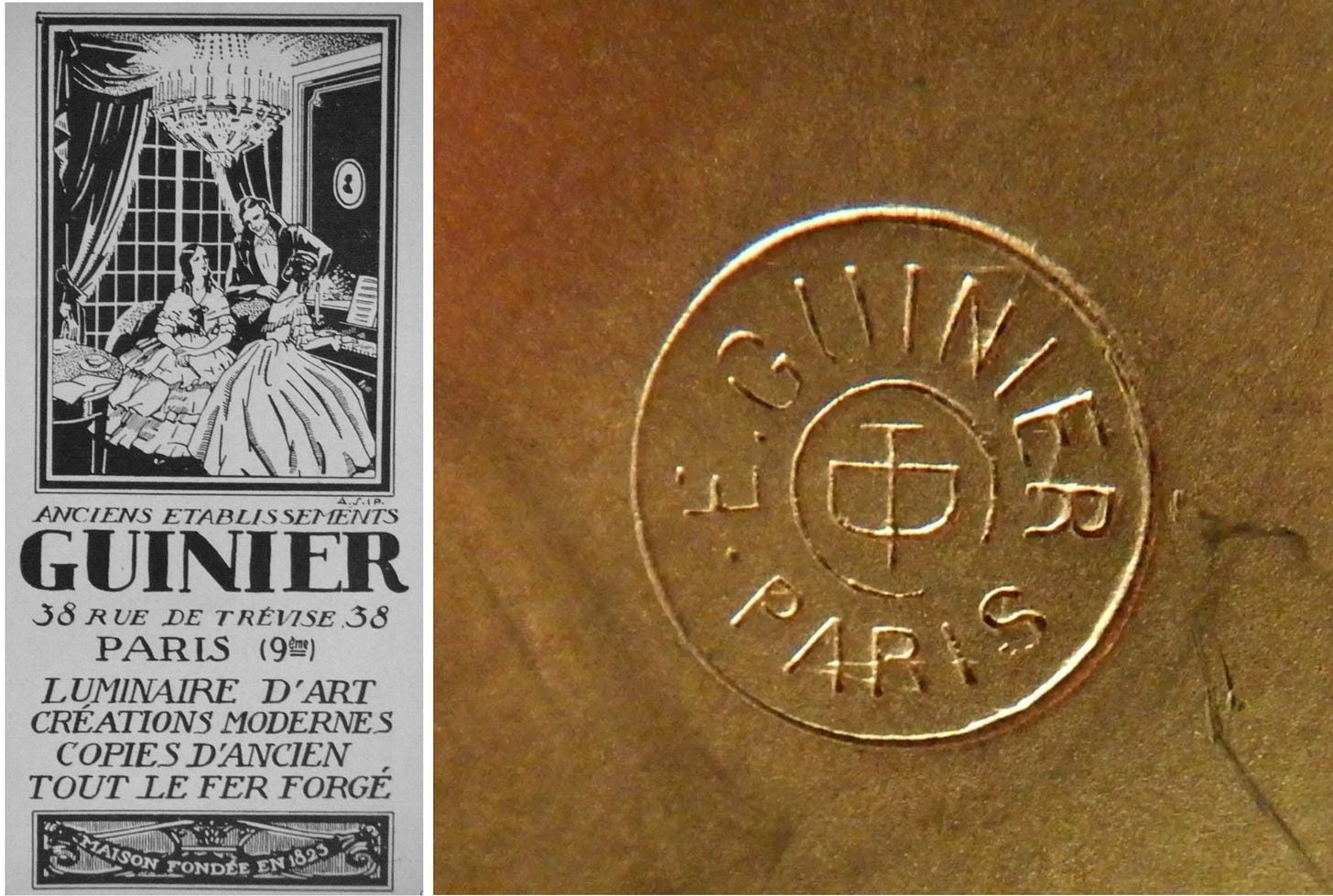

It’s worth noting that the bronze foundry that made at least some Méliodon lamps was the Établissements Édouard Guinier36. It was a metal craftwork company specialising in artistic lighting fixtures, both in wrought-iron and bronze. Édouard Guinier had been a participant in the 1900 Exposition universelle, its first major exhibition, in the Classe 97 (Bronze, fonte et ferronnerie d’art, métaux repoussés), with bronze lights, both in historicist designs and Art Nouveau style37, for which he received a gold medal. He was also awarded grand prizes for his works in the international exhibitions in Saint-Louis (1904) and Liège (1905)38.

In Paris, its workshops and exhibition halls occupied a significant chunk of the rue de Trévise (nos 34 to 40), literally on the same city block as the Gallé historical depot, located on the adjacent street, 20-22 rue Richer, less than 150 m away. Guinier and Gallé were thus practically neighbours in Paris, and it would be easy to read more than a coincidence in this location, when it comes to the existence of the Méliodon lamps with a Gallé shade.

But, to the best of my knowledge, Guinier’s name does not appear any more than Méliodon’s in the Gallé archives or in the publications about Gallé. It’s not among the retailers of Gallé, nor does it appear to have regularly used Gallé glass to complement its line of lamps’ mounts. Émile Gallé and later the Établissements Gallé had chosen to make themselves, in their workshop, all the metal mounts, feet, and bases required for their line of lighting fixtures. There’s no record of a collaboration with an artistic lamp maker like Guinier. On the contrary, Gallé took pride in making the metal fittings of his lamp and advertised the fact in his writings as well as in the published pictures of these pieces, as the 1903 Guérinet album demonstrates, for instance.

What could have happened though, is that Guinier or another retailer/editor of Méliodon’s Daphne lamp bought some Gallé bulb covers from the Paris depot or even perhaps from the factory and fitted them on some specimens of the lamp. This could have been done at the request of some customers too. Unmounted shades and bulb covers, réflecteurs, were indeed available from Gallé, as shown by the stock inventory of the Paris depot in August 1920. This document, made at the occasion of Albert Daigueperce’s replacement by Willy Mohrenwitz, lists five different réflecteurs, some of which seem to have been without any mount. Two of them are Ombelles models, with inventory numbers 65,954 and 65,955 which point to an early 1912 making39 — so they would be different from the Est-Ouest auctions umbel shade pictured at the beginning of this paper. Furthermore, when the Daigueperce Gallé collection was auctioned off by Arcole in 1989, it still had several specimens of unmounted shades and bulb covers40. Among them, the #109 belongs to the same naturalistic orange and green series (often counterfeited, one must add) used on the Méliodon-Gallé lamp sold by Millon in 2013. This looks like the confirmation that some of the Méliodon Daphne lamp might have been fitted early on (rather than in the late 20th c.) with a Gallé shade, but not as the original design and not with Gallé explicit collaboration.

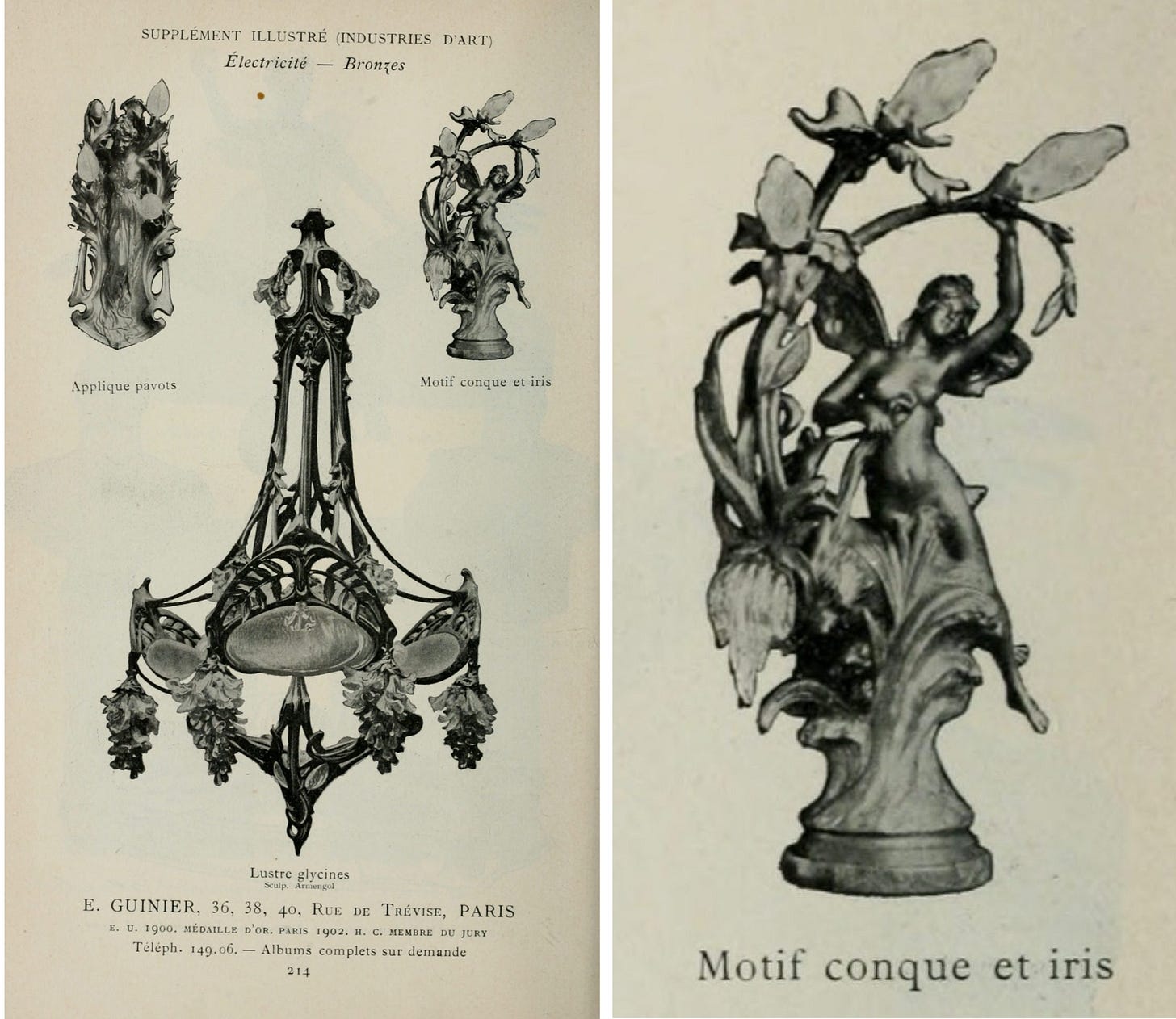

As for the Méliodon lamp, it fitted rather well in the Guinier line of products, if one can judge from the examples given in the illustrated supplement to the 1903 Salon des Artistes français’ catalogue41. Two of the models belong to the Woman Flower genre and they both sport complicated custom-shaped light bulbs, especially the Conque et iris one, without any bulb cover. These suggest that the Méliodon lamp was equipped with its custom-shaped light bulb too, and that it did not need a bulb cover nor a shade. One cover-less specimen of the lamp, fitted with a custom bulb, was sold last April in Pasadena and gives an idea of the intended effect — even though both the socket and the bulb look modern (see above).

Émile Gallé and artistic lamp mounts.

Of course, in Émile Gallé’s time, some of his most exclusive glass artworks could receive a precious metallic mount (gilded silver or other), for which some prestigious silversmith or jewellers were commissioned (e.g., Bonvallet, Falize and Sandoz)42. But this was an entirely different matter. And Émile Gallé was wary of letting a jeweller’s embellishment takes precedence on his own glass artwork, as he plainly explained on one occasion to the director of the Gazette des Beaux-Arts, in 1889, about a vase with a mount by Émile Froment-Meurice.

In his exhibition for the 1889 Exposition universelle in Paris, the goldsmith had included a Gallé vase in rose crystal with a vermeil mount in the Louis XV style. L. Falize had admired the vase and wanted to include its picture in his review of the goldsmiths’ exhibitions in the Gazette43. Consulted on the matter, Émile Gallé protested in a letter to Alfred de Lostalot, on the 19th August 1889, that this vase was his “only by its material”, that “it could not even feature his signature” because Froment-Meurice had acquired it from a third party and had it fitted with a chiselled mount “without any particular meaning”. Émile Gallé then concluded that Lostalot could indeed publish a picture of the vase in the Gazette, but only as “a goldsmith’s work, as an ideal of a precious piece of jewellery, but from Froment-Meurice, without putting Gallé in play in any way and without betraying the true way”44.

This small incident is revealing on Gallé’s views about the reuse of his glasswork by other artists. It reinforces the view that the authorised fitting of his lampshades, even from industrial series, on elaborated sculpted mounts such as Méliodon’s “Metamorphosis of Daphne” would be preposterous. The glass component of the lamp is clearly secondary in importance to the sculpture of the lamp-stand: as we’ve seen, it was most probably foreign to the original design in the first place. This is amply demonstrated by the existence of multiples specimens with glass from different makers. One could also add that the woman theme of the design would have put off Gallé, who had all but abandoned it in his artwork after 1889. Émile Gallé could probably have come up with such a design on his own, in a collaboration with Victor Prouvé as a sculptor for instance, but the glass shade would have been from a different technical and artistic level than what is seen today on some specimens of Méliodon’s lamp. But, again, the full introduction of the electricity in Gallé’s art was far too late in his career to allow for this kind of theme or design, as do attest his multiple lamps, all in the floral or more broadly botanical realm.

Conclusion: a later “marriage” of parts.

To summarise, a few highly probable (but still not definitely proven) salient points can be made about these lamps:

they are the creation of the sculptor Jules André Méliodon, ca. 1900-1910;

the design is a depiction of the mythological theme of the nymph Daphne changed by Zeus into a laurel tree to escape Apollo;

although a plurality of these lamps sport a Gallé bulb cover, Émile Gallé and Établissements Gallé have nothing to do with this design, for this was certainly not an artistic collaborative project between the glassmaker and the sculptor.

the original design as sold by Guinier probably sported a custom-shaped bulb and had no bulb cover. Once this bulb was lost, owners or dealers of these lamps took upon themselves to fit them with new or salvaged shades from famous Art Nouveau glassmakers’ lamps, to sometimes great effect, it must be said.

Definite proof that these lamps are a marriage of parts could come from a Guinier sales catalogue, if one can be found, and if it advertised this particular model.

[NB : the paragraph regarding the Daigueperce Gallé bulb cover was added on 22 August 2021]

© Samuel Provost, 21 August 2021.

Footnotes

There is a file about this model in the Musée des Arts Décoratifs (Centre de documentation des arts décoratifs, AN-AD Meliodon, CAD513947), but I haven’t had the chance to review it.

Justine Posalski, Les luminaires Daum: de l’objet utilitaire à l’œuvre d’art, Mémoire de master 2, UPMF Grenoble, 2015, 2 vol. HAL Id: dumas-01266837.

Musée de l’École de Nancy, Thomas V., Sylvestre F., Olivié J.-L., 2014, Émile Gallé et le verre: la collection du Musée de l’École de Nancy, Paris, Somogy éditions d’art, no 371 p. 203 and no 380, p. 207.

Louis de Lutèce, “Au Musée Galliera, Exposition de la verrerie et de la cristallerie artistiques“, Notes d’art et d’archéologie, Revue mensuelle de la société de Saint-Jean, 22, 1910, p. 130-132, esp. p. 131 [link].

Catalogue illustré de la Société nationale des beaux-arts, Salon de 1902, Ludovic Baschet, 1902, no 169 p. XLIX.

A specimen of his personal visit card is in the Meissonnier archives, a testimony of his interest for the fine arts: http://bibliotheque-numerique.inha.fr/viewer/2489/?offset=1#page=80&viewer=picture&o=bookmark&n=0&q=.

A part of the family genealogy: https://gw.geneanet.org/garric?lang=en&p=marie&n=meliodon. See also La Liberté, 18 March 1895, for a mention of a private musical evening hosted by Méliodon and his daughters.

Grund, 2006, vol. 9, Maele-Muller, p. 729-730.

The first one seems to be Leonard Forrer, Biographical dictionary of medallists, vol. 4 [MB-Q], London, 1909, p. 14. See also Glenn Opitz, Dictionary of American Sculptors, Poughkeepsie, 1984, p. 269.

État-civil de la Seine, registre des naissances pour 1867, no 1365.

Archives de Paris, Registres des matricules du recrutement militaire de la Seine (1887), no 1987. He was reformed in 1893, due to some chronical bronchitis and was therefore not recalled up for the First World War.

Bulletin officiel du ministère de l’Éducation nationale, 48, 1899.

Société des artistes français, Catalogue illustré de peinture et sculpture. Salon de 1894, Ludovic Baschet éd., Paris, 1894, no 3386 (“Portrait de M. Colomb – buste, plâtre”).

In 1895, he offered a marble statue of Narcisse (Société des artistes français, Explication des ouvrages de peinture, sculpture…, Paris, Paul Dupont, 1895. In 1903, he has two: no 2992, Recueillement, no 2993, Qui dort dîne. Société des artistes français, Catalogue illustré de peinture et sculpture. Salon de 1903, Ludovic Baschet éd., Paris, 1903.

Journal des artistes, 8 June 1902, p. 3823.

Jules André Méliodon, Charles André Lesueur, 1904, Collection du Centre national des arts plastiques [link].

See the note on France Archives. Archives nationales AJ 15 525 and F/21/4246, file no 17. Philippe Poite, Documentation sur une collection de bustes retrouvée et conservée par la Grande Galerie de l’Evolution, Paris : Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Département des Galeries, 2003. (Série Rapports, SCC/Rapp. 03/21), pages 39-42.

His name, mistakenly spelled as “Mélodion“, appears in a published list of Free Masons in 1908: Répertoire maçonnique, contenant les noms de 30000 francs-maçons de France et des colonies, relevés dans les archives de l'Association antimaçonnique de France [link].

It was a letter in favour of the colonel Picquart, published in L’Aurore: Méliodon sent his signature to the leftist newspaper Le Radical : L’Aurore, 6 December 1898, p. 4 [link]. His address was then 58, rue Traversière in Paris.

Collection Maciet, Bibliothèque des Arts décoratifs, Paris, quoted by Neil McWilliam, Monumental Intolerance: Jean Baffier, a Nationalist Sculptor in Fin-de-Siècle France, Penn State Press, 2000.

Procès-verbaux du Conseil de Paris, 1900, p. 352.

“Un ouvrier artiste, un sculpteur qui gagne sa vie, durant toute la journée à des travaux industriels, et qui, le soir, se livre à l’art” : Les Questions actuelles, revue documentaire, 54, 1900, p. 72 (the emphasis is mine).

One cannot fail to remember Victor Prouvé’s sculptural work for the Université Populaire’s building entrance in Nancy, rue Drouin, at the same time.

Vincent Duclert, “L’affaire Dreyfus et la gauche”, in Histoire des Gauches en France, 2005, p. 197-214 [link]. In his speech, Jaurès was calling for the advent of “la République vraie, à la République du peuple, à la République sociale !”.

“La République du Peuple. Prime à nos Lecteurs”, Le Cri du Peuple, 20 October 2001 [link]. The advertisement was repeated verbatim in the 17th November 1901 issue.

Attributed to Jules Méliodon, La République du Peuple, Côte Basque Enchères Lelièvre - Cabarrouy, 27 March 2021 lot #436. One wonders why the artwork is only attributed to Méliodon when his signature is plainly readable. But this useless caution is nonetheless interesting because it supports the idea of a misread “JA Méliodon” inscription as the beginning of the “M Méliodon” signature (see above).

Archives de Paris, VR 469, Direction des Beaux-Arts de l’Architecture, Bibliothèques et beaux-arts 1812-1962, Subventions. 1903. Concerne les secours à MM. Meliodon et Guillou [link]. Non vidi.

The Paris-adresses : annuaire général de l’industrie et du commerce (Ch. Alavoine et cie, Paris, 1907, p. 2429) gives 15-17 avenue Ledru-Rollin as his address in 1907. He is registered as a sculpteur statuaire.

But see David Karel, Dictionnaire des artistes de langue française en Amérique du Nord, Musée du Québec, 1992, p. 897.

Judex, “Le concours de la réunion des fabricants de bronze”, Revue des arts décoratifs, January 1900, p. 32 [link]. See also “Discours de M. E. Coupri”, Annuaire de la Réunion des fabricants de bronze de la ville de Paris, 1900, p. 33-34.

Léon Riotor, Les arts et les lettres, 3e série, Paris, Lemerre, 1908, p. 132-133.

The “E. Guinier” stamp under the base is not always mentioned in the sales records of the lamps and proper pictures are lacking more often than not.

Catalogue général, groupe XV, classe 97, no 56, p. 14: “Guinier (Édouard) (A. et M.), à Paris, rue de Trévise, 36 et 38. – Bronzes d’éclairage. Électricité : Décoration appliquée à l’électricité. Modèles et styles dérivés d’anciens. Modèles en art nouveau. PL. I. — C. 2 et B. 3”. See also the general report on the classe 97: Henri Vian, Exposition universelle internationale de 1900 à Paris. Rapports du jury international. Classe 97. Bronzes, fonte et ferronnerie d’art, zinc d’art, métaux repoussés, Impr. nationale, Paris, 1901, p. 48 [link].

Comité français des expositions à l’étranger, Bulletin officiel, no 1, January 1908, p. 173 [link].

Inventaire de clôture de la gérance Daigueperce arrêté le 31 août 1920, Archives Gallé Charpentier (private coll.).

Exceptionnel ensemble de 200 œuvres de Émile Gallé provenant de la collection d’un de ses collaborateurs et à divers, Arcole, 2 June 1989, Drouot Richelieu, #107 to #110, p. 41.

Société des artistes français, Catalogue illustré de peinture et sculpture. Salon de 1903. Supplément illustré (industries d'art), Ludovic Baschet éd., Paris, 1903, p. 214.

See Maurice Demaison, “Les montures de vases”, Art et décoration, July 1902, p. 201-208, with several Gallé vases illustrated.

L. Falize, “Exposition universelle de 1889, les industries d’art. II. L’orfèvrerie”, La Gazette des beaux-arts, 1889, p. 197-224, esp. p. 209 and plate p. 434.

Letter from Émile Gallé to Alfred de Lostalot, 19 August 1889, Autographes des siècles.

Bibliography

• Duncan A. and De Bartha G. 2013, Gallé Lamps, Woodbridge, Antique Collectors’ Club Ltd.

• Posalski J. 2015, Les luminaires Daum: de l’objet utilitaire à l’œuvre d’art, Mémoire de master 2, UPMF Grenoble, 2015, 2 vol. HAL Id: dumas-01266837.

• Musée de l’École de Nancy, Thomas V., Sylvestre F., Olivié J.-L., 2014, Émile Gallé et le verre: la collection du Musée de l’École de Nancy, Paris, Somogy éditions d’art.

How to cite this article : Samuel Provost, “The Metamorphosis of Daphne : on Méliodon’s and Gallé’s lamps”, Newsletter on Art Nouveau Craftwork & Industry, no 13, 21 August 2021 [link].