Understanding Gallé Labels (I): the different types.

A preliminary guide to the various labels used by Émile Gallé and Établissements Gallé.

One little understood documentary evidence for dating the Gallé series is the paper labels glued under their base. There are half a dozen different types known over the whole history of the company and nobody has really tried to make sense of them. But they could be important in several ways to increase our knowledge of the Gallé factory, its marketing strategies and above all the precise dating of the objects themselves. In a previous essay where I presented a tentative assessment of the Cristallerie Gallé’s total quantitative output, I made some heavy use of the lots’ numbering most of these labels do feature. In this new paper, I will go back to the subject of the labels themselves and present what can be said about their different types and uses. I will complete this study in a second paper with the publication of some partially preserved lists of lot numbers that provide a reliable way of dating the objects that sport them, and by extension, the corresponding series.

The following overview of the labelling system relies on more than six years watching the online antiques’ market and looking for these labels. I am not claiming to have done a universal watch for these, far from it, but I have regularly checked the most important auctions aggregators in France, Europe, and the US. I have also scoured the auctions archives for some of these. Finally, I have benefited from the friendly help of several correspondents, the first among whom was Justine Posalski who has regularly sent me some pictures of specimens I did not know of. I am very grateful for this help and I would ask other experts, dealers or collectors who may have some label marked Gallé glass to please share them, so we can refine this preliminary study.

A neglected subject in the studies about Gallé.

Few mentions in the previous Gallé literature.

It’s true that these labels present quite a challenge because of the total lack of relevant information available until now, which is of course completely understandable. This was a small technical matter, an object of curiosity rather than a subject of serious study to most of the authors of books on Gallé. Usually, they are often collected with the signatures and feature on a separate table without much of an explanation :

Philippe Garner did include two pictures in his richly illustrated Gallé (1976, p. 105) but these are not the more common types and there’s no comment of them in the text.

Carolus Hartmann has three of them in his lexicon’s article on Gallé (cat. 7177-7178 [double], 8164 and 6183), bundled with the hundred plus signatures he collected for his reference Glasmarken Lexikon (1997). He bizarrely omits two of the more frequent types.

François Le Tacon does not picture them in his seminal monograph on Émile Gallé’s glass (1998)1 but he gives a list of types, with a rough chronology. He underlines the parallel use after 1904 of the Emile Gallé Nancy Cristallerie and Emile Gallé Nancy Paris types, before venturing that, after 1918, the Cristallerie Gallé Nancy remained the sole type.

Philippe Olland has six of them in his dictionary (2016), which reflects the progress made on the subject since 1998. He mixed their drawings with some paper letterheads and advertisements2, and proposes a different chronology: ca. 1894 for the Emile Gallé Nancy Paris and the E☨G types, 1894-1914 for the Gallé Nancy Paris, 1895-1900 for the Cristallerie d’Art Emile Gallé Nancy Paris, ca. 1895-1897 and after 1920 for the Cristallerie Gallé Nancy, and finally after 1920 for the Etablts Gallé Nancy Paris.

And these last two are the only authors to briefly discuss the matter: it’s otherwise absent from important monographs such as the universally quoted Gallé glass (1984) by A. Duncan and G. de Bartha, the Émile Gallé Le magicien du verre (2004) by Ph. Thiébaut or the two books by T. Esveld, to cite only some of the vast Gallé literature. At most, labels incidentally appear in the compendium of signatures featured in some collections or exhibitions catalogues because they are partially covering the signature on the bottom: it’s the case in the posthumous publication of B. Hakenjos’ doctoral thesis (cat. sign. 86), Émile Gallé (2012), as in The Gerda Kœpff collection (cat. 33), or in the more recent Russian exhibition catalogue Linii Gallé (cat. no 106 and 350). But they are more than often simply ignored.

At best, these labels are regarded — and used — by the experts as some material evidence that contributes to establish the object’s authenticity but cannot be relied on too much given the lack of information about them.

Many types of potential labels, few specimens preserved.

Another issue is that the original labels from the Gallé company are not the only ones featured on the pieces: the retailers had theirs too, which are equally interesting to trace back the marketing of an object, and more generally the retailers’ network of Gallé. Such famed specialised stores as L’Escalier de Cristal, A la paix, or Le vase étrusque had their own paper labels, which are not our concern here, but are worth noting because they can help identify some exclusive series, among other information. The country-of-origin stamp that marks some 1920s glass will not be part of this essay either3. It’s enough for the time being to note that, like the signatures, this stamp can be used as a corroborating piece of evidence to date the use of a paper label on the same piece, but this is an exceedingly rare occurence.

The proportion of preserved labels is very low, as it should be: buyers of Gallé glass got rid of them in their vast majority, as they would have done for any manufacturer’s label or price tag on any object. A few of them did keep the label on, some of them because they simply did not care removing it, and others probably because they likened it as a supplementary authenticity marker besides the signature on these prized possessions — the same way some of these buyers also kept the original invoice from the retail shop. These labels’ location on the underside of the vases or lamps was at the same time increasing and hurting their rate of preservation. On one hand, it meant that they were all but invisible to the onlooker (except perhaps on a few clear glass series) and so could be left untouched ; on the other hand, and this was the bigger effect, they were easily smeared and abraded by the repeated contact with the surface the glass was kept on, not to mention the high risk of being soaked in water, given the inherent function of most of these objects (as vases). A high proportion of these preserved labels are therefore without surprise only partial ones.

Moreover, there is a good reason to believe that not all the Gallé items did sport one of these because it was not always needed, in particular for the direct sales from the factory.

Finally, it must be noted that our enquiry failed to uncover any paper label preserved on furniture. It may represent a statistical oddity only, due to the considerable disproportion between glass, earthenware, and wood objects available on the market today because from a technical point of view there was no difference in the way these three categories’ inventories were treated.

Missing or incomplete descriptions.

This essay is also a call to action for the auction houses’ experts and antiques’ dealers: they really have to do a better job at describing any label that may feature on the glass items they’re selling. Better yet, they should always take pictures! For every label correctly described (type, inscription, and number if there is any), there are scores of allusive or vague descriptions: “paper label”, “factory paper label”, “original printed manufacturer paper label”, “porte l’étiquette d’origine”, “étiquette adhésive originale“ (how do they know ?), “étiquette au revers”, “étiquette au-dessous” (what good does it do if they do not say anything about it?), “étiquette ancienne de la cristallerie sous la base” or “étiquette de la cristallerie Gallé” (can they be more specific?), and so on. This is hardly helpful and quite frustrating.

If there is no number inscribed or if it’s been erased, smudged or tore up to the point of being illegible, could they just say it? This is potentially a useful piece of information. Negative information is better than none. Even without a number, the description can be useful because, as we’ll see, the type of label can be correlated to the sale’s date (if not the making) of the object that features it.

The correct way to do it, if no picture is provided, is as follows : “ancienne étiquette circulaire "GALLÉ NANCY PARIS" marquée à la main 208” (a random example, in this case from an hibiscus lamp foot at Rouillac, 2011-06-27 #139).

Forged and original labels on fake glass.

The matter is furthermore complicated by the possible forgeries involved. Labels are of course far easier to forge and to manipulate than the glass items themselves. Given the wide array of fake Gallé items on the market today, one has to expect that some labels are forged, whether they are affixed to fake Gallés or not.

For instance, the vase pictured above looks like a genuine Gallé vase with a pattern of common polypody fern and moss, and it features the expected Mk III signature, for a ca. 1908-1920 date. However, the round label glued on its lower side is not only in the wrong place but shows a slightly different design from the true E5 EG-NP type (Émile Gallé • Nancy•Paris). The typeface is different, there is only one encompassing circle instead of two, with the same line width ; the dotted lines for writing the central number are missing, and this figure is decidedly not from the same writing as most of the preserved labels. What probably happened here is that an owner of the vase forged a label but did a bad job of it and worsened it by picking a preposterous location on the vase for it. To add insult to injury, it looks like the culprit chose a number that reads like a date (1899) on purpose, as if a cameo industrial series of this type could belong to such period.

But many of these forgeries could very well be “true fake labels”, meaning genuine labels lifted from their original item (because it’s been damaged or simply because it’s a small low-value glass object) and glued back under the base of some costlier, more prestigious Gallé glass, to add it a little more value or authenticity.

The universal lack of understanding regarding the function of these labels and their chronology (at least until now, that is) is a small mercy here. It means that the forgers are most likelier than not to make a blunder in using these genuine labels as a mean of authentication, adding value to the glass. This lack of sophistication in understanding the Gallé company’s markings on their products has already been a way to identify forgeries among the signatures, as I demonstrated elsewhere in the case of the infamous fake Gallé advertisement triptychs.

In the case of labels, an obvious example of such a very suspect oddity is an enamelled vase sold in Lausanne in 2017 (pictured above). The vase has a large intaglio signature under its base, “GALLÉ déposé”, from a type belonging to the early years of the cristallerie in Nancy (mid-1890s), which could be enough for its authentication. But it also features an E6 G-NP type label inside it, glued on the bottom. While one can imagine why it was put here — to prevent it from hiding part of the signature — this is patently absurd for several reasons. First, the Gallé employee in charge of labelling had no qualms about sticking a paper label over an engraved signature on the bottom of a vase. That much is clear from several preserved examples4. The Gallé • Nancy•Paris type, as will be established later, is a very late one, from the 1920s: it’s fully incompatible with such a glass piece (enamels from the 1920s are markedly different) as it is with such a signature – the “déposé” mention at such a date would be preposterous. And that’s not even contemplating the impractical aspects of such a location — to spell the obvious, it’s a vase, a vessel meant to hold water. To a careful observer, this label has therefore the opposite effect to what was probably intended with its addition — for it’s most certainly a later addition — casting a doubt on the overall piece.

Other examples are more of the open-and-shut case type. The purported Gallé lamp from the 1920s pictured above belongs to a South American collection. A simple glance at the lamp is enough to rule it as a crude forgery: the decorative pattern, the colours, the awkward signature (a rather poor imitation of the Mk III type) all signal what’s probably a cheap early 21st c. fake. What’s interesting though, is that despite the poor overall quality of this imitation, the base presents two additional details supposedly vouching for its authenticity, a “France” rectangular stamp close enough to the type used in the 1920s for the US market, and a circular paper label. It’s a E6 G-NP type label (Gallé • Nancy•Paris), marked with a handwritten “125”. It looks genuine and must have been lifted from another piece, unless it’s an excellent copy. Either way, this nice touch is every bit desperate on such a bad fake lamp.

A corpus of preserved labels.

These kinds of forgeries excluded, the digital collection of preserved labels I managed to gather, as of May 2021, contains 164 different specimens. While it may amount to only a fraction of the available material over the last decades, it looks like a sample representative enough to support a preliminary study. Like for the Gallé signatures, I expect to revisit this subject in the future, when more material will have been made available, thanks to the new awareness this paper will hopefully generate.

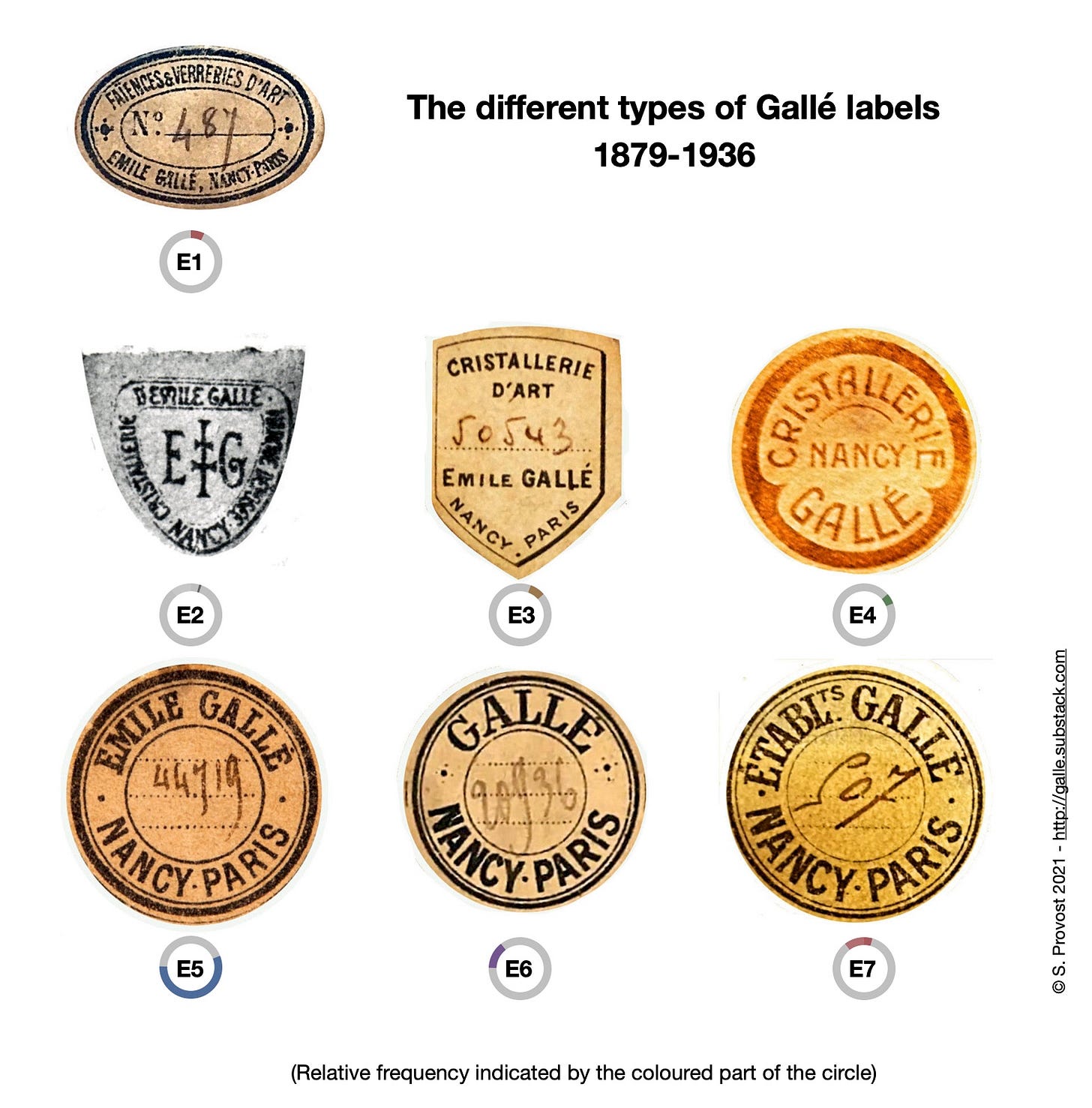

As I have done for the signatures before, I will suggest here a new naming scheme for the different types of Gallé labels, to facilitate the discussion and further reference by avoiding the complete quotation of their inscription. Gallé glass can thus possess the following labels, presented in a rough chronological order, to be discussed in the detailed examination below:

E1. FVA-EG-NP : FAÏENCES ET VERRERIES D’ART – ÉMILE GALLÉ – NANCY PARIS.

E2. E☨G : E☨G – CRISTALLERIE D’EMILE GALLÉ • MARQUE DÉPOSÉE • NANCY.

E3. CA-EG-NP : CRISTALLERIE D’ART – ÉMILE GALLÉ – NANCY PARIS.

E4. CG-N : CRISTALLERIE GALLÉ – NANCY.

E5. EG-NP : ÉMILE GALLÉ • NANCY•PARIS.

E6. G-NP : GALLÉ • NANCY•PARIS.

E7. ETG-NP : ÉTABL(issmen)TS GALLÉ • NANCY•PARIS.

The general naming scheme stayed the same throughout the history of the Gallé company: the designation of the company followed by its location. Like in the case of the signatures, the assumption is that changes in the labelling system were not gratuitous but that they reflected some important modification in the marketing strategy or more simply in the stock inventory’s practices. One goal of this paper is precisely to track down some changes from the corpus of preserved specimens.

The first observation is that none of these labels can be older than 1877 when Émile Gallé took over the company from his father, since they all sport his first name. The second one is that the abbreviated nature of the inscription on these labels prevented the full transcription of the complete company name as it appears on letterheads and invoices for instance. This would otherwise provide a simple enough way of corroborating the dates for these labels. However, this would not be enough to resolve the matter because it seems — pending some verification from a study of such evidence — that Émile Gallé and his heirs made some changes to these letterheads more often than was required by actual changes in the company’s structure or practices.

E1. FVA-EG-NP : FAÏENCES ET VERRERIES D’ART – ÉMILE GALLÉ – NANCY PARIS.

The oldest known type of label has an oval shape delimited by a double black border. The text in small capitals follows on the inside this border and is separated from the center field by a thin line. An abbreviated No(umber) and a dotted line indicate where the employee writes the lot’s number in the center. Attested numbers run for the very limited sample available (7 specimens) from 6 to 29183. As the designation implies, this label supposes that Émile Gallé already has a permanent outlet in Paris. It also implies that there was no different count for the earthenware and the glass shipments from the Nancy factory. The known specimens support this conclusion. The few labels available are encountered on earthenware as well as on glass, mainly enamelled early glass from Meisenthal, like the vase from the Funke-Kaiser collection in Köln above5. This leaves no doubt on the fact that this was the label used from the opening of the Paris depot in 1879.

The two lowest numbers preserved, 6 and 7, come from the same collection and provide an insight on the labelling process: both glass pieces, a four-lobed low cup and a small vase, were purchased by N. Guriev in the Gallé depot in Paris, in 1897, for the Russian imperial collections where their subsequent history is well documented6. The two pieces themselves are well compatible with such a date. It’s therefore clear in this case that the handwritten numbers do not reflect the general lot number system but a special order for a prestigious client. In all probability, the numbering was specific to this purchase and the labelling done by Daigueperce on the spot. The acquisition information is important because it rules out another explanation for such low inventory numbers, i.e., that they came from the newly opened depot in Frankfurt (February 1897), which must have initiated its own lot counting this same year. The Guriev testimony confirms that there were different parallel numbering of the pieces and lots, even when they came through the same depot, in this case Paris. This makes of course the understanding of these numbers’ series all the more problematic.

When did they stop using this label? The last attested number (29,183) looks compatible, from the theoretical distribution of the lots’ numbers through the years (more on that in the second part of this essay), with a 1896 date, that is shortly after the opening of the cristallerie in Nancy. A momentous occasion like this would, of course, make sense for a change of some inventory and marketing practices. However, given the small size of the sample, nothing guarantees that this E1 type final count was not several thousands or higher. The labels on the 1897 specimens bought in Paris for the Russian tsar could be more than leftovers and prove that, at this date, they were still the main type in use. On the other hand, its phasing out in the mid to late 1890s makes sense in the greater scheme of the Gallé company evolution. The pivot from earthenware to glass in this period meant that Gallé ceased to see itself as a faïence company first, and that had to have some consequences on the labels it used. In this regard, an earlier rather than later switch to the various “Cristallerie” labels looks more sensible.

E2. E☨G : E☨G – CRISTALLERIE D’EMILE GALLÉ • MARQUE DÉPOSÉE • NANCY.

The second type is the rarest of all. I could find only two referenced vases featuring it and unfortunately none of their sales descriptions had a picture for it. So, the sample is again far too small to make sweeping statements about this particular type. They make it clear, though, that it was indeed this same type, whose only picture I know is in Philippe Garner’s book (above)7. There are also two line drawings in Hartmann’s handbook8 – and one in Olland’s dictionary most probably derived from it – the second coming from the Bulletin officiel de la propriété industrielle et commerciale. The label design was, in fact, registered in 1894 with the trademark, so its beginning is well established. The “marque déposée” mention in the label’s design, that mirrors some Gallé signatures from the 1890’s to 1902, is an important chronological clue in this regard: 1902, the last year Émile Gallé registered his designs with the prud’hommes’ office in Nancy, must be regarded as a terminus ante quem for the use of his label.

According to Hartmann, the E☨G mark on some of Émile Gallé’s glass, which is older than the label since it appeared on pieces for the 1889 Exposition universelle, signals series made for the Escalier de cristal store owned by the Pannier brothers in Paris. Did the label indicate an exclusive marketing strategy of this kind? That would perhaps explain the lack of numbering space on it. It wouldn’t have been meant as a shipment/inventory tracking device but as an authentication mean.

It’s worth noting, though, that both vases sporting this label in the sample were prestigious artworks presented by Émile Gallé in major exhibitions from 1898 to 1900. That could provide an alternate hypothesis, that this label was marking glass series associated with an exhibition in Paris.

One last note regarding this label is that it had a roughly similar shape as the E3 type (i.e., not round), whose beginnings could have been contemporary but which was designed to have a handwritten lot number.

E3. CA-EG-NP : CRISTALLERIE D’ART – ÉMILE GALLÉ – NANCY PARIS.

This is a shield or badge shaped label found on early cameo glass series as well as on some older enamelled ones. Its inscription is remarkable by the “cristallerie d’art” designation — the only one to do so. It has a central dotted line to be filled with a handwritten number. On the few specimens from our corpus (14), this label frequently covers an older rectangular one. The written numbers run quite high with a preserved specimen in the Gerda Kœpff collection reaching 85,804 and several between 49,000 and 59,000. Some corresponding vases can be quite recent, like a small “banjo” shaped soliflore or an Ombelles candy box featuring a Mk III signature. On the other hand, the earlier pieces of glass featuring this label are enamelled or marqueterie vases from the 1890s . The lots’ numbers these possess are very high (over 37,000), a fact that reflects a likely continuation of the count from earlier labels’ types rather than a reset. It confirms that, in general, the lots’ numbering on these labels is independent of the labels’ type.

Some inconsistencies exist in the sample, with some very low numbers (e.g., 13 on a post-1904 landscape vase, 6,869 on a Mk II signed berry vase9 that indicate alternates counts from the main Paris depot ones.

What transpires from these remarks is that the introduction of this label probably coincided with the opening of the cristallerie in Nancy. It was then discontinued in the mid to late 1900s. A simple but compelling narrative would be to say that Émile Gallé’s death and the subsequent transformation of the company in an industrial art glassmaker prompted the “cristallerie d’art” moniker’s drop out and the switch to the next label, but that’s not the case at all. First, this “cristallerie d’art” or the alternate “cristallerie et ébénisterie d’art“ designations keep appearing on official papers from the company until the 1920s included. Second, at least two (and maybe three) different labels were in parallel use in the late 1890s and early 1900s, this one and the E5 type (plus the E4, with a question mark). And finally, third, the hypothesis that the E3 type would be exclusive to high-end products, because of the “cristallerie d’art“ mention, does not hold either: this label keeps appearing on low-cost objects, such as candy boxes or small soliflores.

E4. CG-N : CRISTALLERIE GALLÉ – NANCY.

The E4 label may be the most puzzling of all. This is a round printed label, the only one in coloured ink — a light brownish red — rather than in black. The typeface is different from the previous and the following labels. Its design shares two unusual characteristics with the E2 type: the lack of a blank space to be filled in with an inventory or shipment number and the sole location of Nancy for the company — Paris is omitted. The wording of the inscription, “Cristallerie Gallé – Nancy”, is quite close to some large engraved signatures on the bottom of some 1894-1897 series (“Cristallerie de Gallé à Nancy”).

It’s a rather uncommon type too, with only 9 identified specimens, coming in 5th place in our sample, but it’s supposedly featured in two very different periods, right at the beginning and at the end of the history of the Établissements Gallé, the late 1890s and the late 1920s. Hartmann, followed by Olland, gives 1895-1897 as its beginning10. This chronology may have been spurred by the resemblance of the wording with some signatures from this early period. But, I could only find it on one piece, a Rosa Gallica perfume bottle (so ca. 1902-1903) and its authenticity could be questioned.

What’s indisputable on the other hand is the prevalence of this label on late 1920s vases, signed with the Mk IV of Mk VI signatures. The most clear-cut instance is a relief Rhododendrons vase series (pictured above), dated after 1924 from this technique alone (confirmed by the signature), whose two nearly identical specimens sport this label11. The James Julia’s one even has two labels, the E4 type but also the E7 one (“Etablts Gallé”), a late 1920s and early 1930s type too (see below), unfortunately smudged here, so no number is legible. The same phenomenon appears on a Hawthorn large pointed cup, Mk IV signed, also from the 1920s, but this time with an E6 (Gallé Nancy Paris) label (pictured below in the E6 paragraph)12. In these instances, the double labelling probably has to do with a complex sales history. As the E4 type does not carry an inventory or lot number, it was necessary to add another one which did. This suggests in turn that the E4 type was in use for some restricted market that has yet to be identified.

E5. EG-NP : ÉMILE GALLÉ • NANCY • PARIS.

The commonest of the Gallé labels presents different challenges. The great variety of glass pieces that feature it makes clear that it was in use during the whole industrial era of the Gallé company. It’s the first of three very similarly designed labels (with the E6 and E7), with a round shape, the company’s designation with its double location, Nancy-Paris, on the external band, while the center has three dotted lines to receive the handwritten lot number. Quite often, this label is glued on top of another one (the stock inventory one), as in the case of the E3, E6 and E7 types.

The written lot numbers in our sample run from 1 (in several copies!) to 94,937, a Mk IV signed poppy soliflore I have already highlighted in the essay on this signature’s type and tentatively dated from late 1920. But it’s evident from the range of attested signatures on the corresponding

glass pieces (from pre-1904 types to the late 1920s Mk VIII) that this label was still in use in the 1920s and probably even the early 1930s. I will therefore leave for the second part of this essay a more detailed discussion on the chronology.

E6. G-NP : GALLÉ • NANCY • PARIS.

The E6 type has the same design as the E5 one, except for the missing first name, Émile. The sample’s written numbers run from 5 to 31,608 on vases featuring Mk IV to Mk VI signatures, with only two outliers: the enamelled vase highlighted in the fake labels section above (clearly a later addition) and a Mk III signed Roses lamp that belongs to those uncommon cases of clearly late 1920s glass pieces featuring this mark. If we add that this is the only type of label other than the ubiquitous E5 to appear on Mk V signed glass, it becomes clear that it was introduced at the same time as these Mk IV-Mk V signatures, i.e., in late 1920. This label was probably part of the reorganisation of the marketing strategy after Albert Daigueperce was ousted from the Paris depot. Only one vase in the sample with this label has a Mk VI (1925-1936) signature. It suggests that the E6 remained in use for a relatively short time, a 5-year span, until it was replaced by the E7 type. That it’s still the second most common type (though very far below the E5 type) just shows how massive was the Gallé glass production in the 1920s.

E7. ETG-NP : ÉTABL(issmen)TS GALLÉ • NANCY • PARIS.

Finally, the last type shares most of its characteristics with the two previous ones. The only change is the addition of the abbreviated “Etablissements” designation before the Gallé name. This makes the determination of its chronology an easy one, for there is no doubt that it was introduced when the Gallé company was incorporated in July 1925 and became the Établissements Gallé SA. The sample of vases available with this label fully supports this conclusion. These are late 1920s glass pieces, with Mk IV or Mk VI only signatures — no Mk III or Mk V early 1920s signatures. The count on these labels from the sample goes from 16 to 33,338 for a small Mk IV nightlight.

General remarks

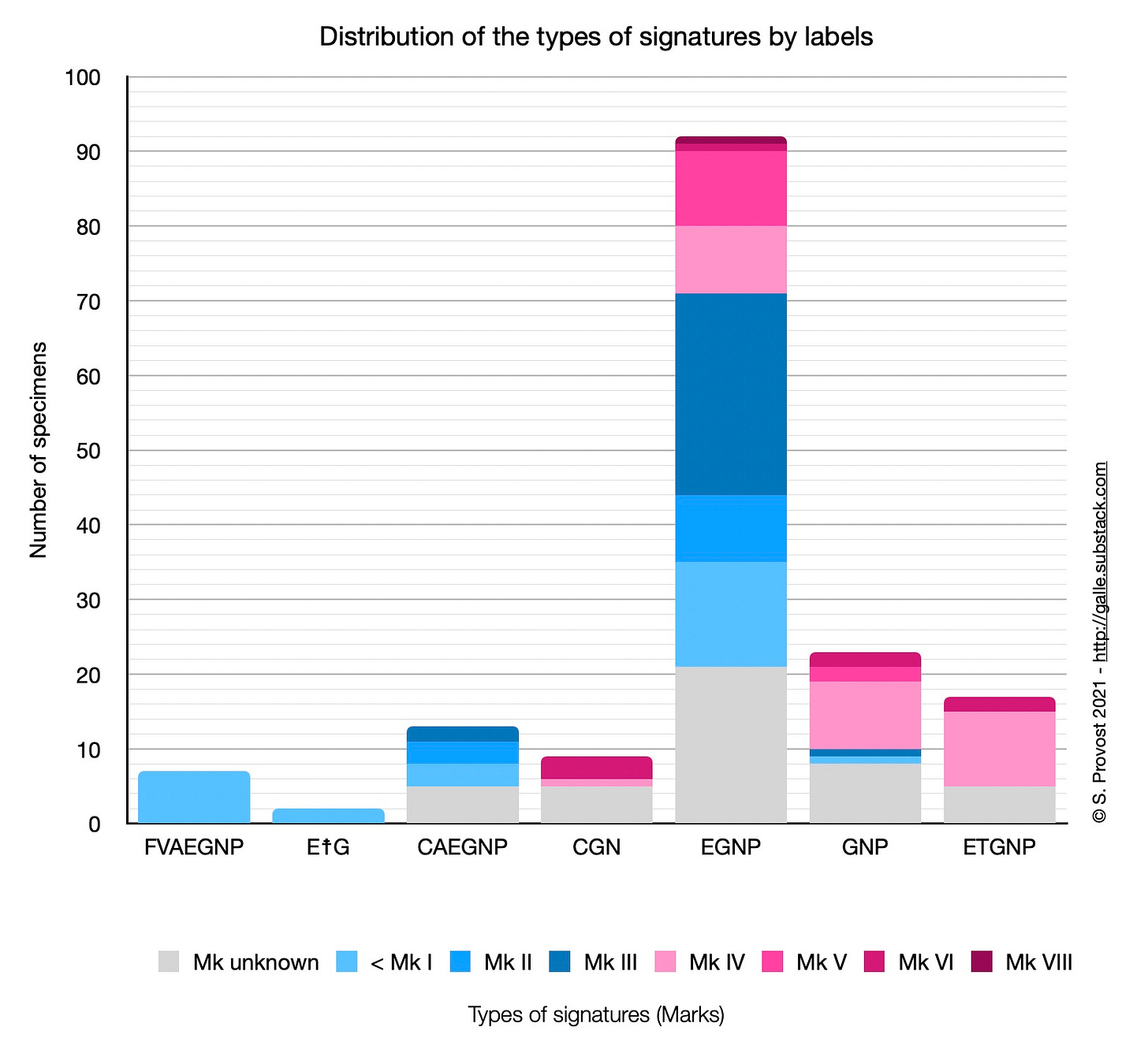

What seems clear from this overview of the different types of labels is that none of them had an exclusive use by the factory at any point of its history, except the E1 for the early 1880s. Afterwards, there were always at least two and sometimes as many as three or four labels in parallel use. This stands in contrast with the signatures’ system, at least for the 1905-1920 period where there was only one mark (Mk II and later Mk III), with minor variations. As the graph above illustrates, there never was a perfect match between a label type and a signature. This plurality of labels underlines probably the existence of different marketing strategies, given that the likeliest explanation is that this labelling system allowed to easily differentiate the markets or at least the types of outlets the vases were sent to.

As it has been already remarked, two of these labels (E2 and E4) are unlike the others, in the sense that their design does not allow an additional handwritten marking. All the other ones have a blank space at the center that can be filled in with a number or another sign, but not these two — in the first case, there is the E☨G abbreviation and in the second one, the Nancy location. This is an important remark because it means that they must have had a different use from the other labels: they simply reinforced the identification and authentification of the item already indicated by the signature — because this signature was hard to decipher perhaps — and therefore had no internal use in the Gallé company. This was for the retailers or even for the clients.

By contrast, the most frequent types were designed to be filled-in by a handwritten mark which would not have had any meaning for people outside the company. This was the lots’ numbers for the shipments to the depots and to the retailers.

The labelling of the glass pieces: where, when and why?

One key observation is that the circular labels in discussion were not the first ones to be sticked to the object. The preserved evidence shows that, at least for the E3 through E7 types’ period, a previous marking of the pieces had taken place, with another simpler label : a rectangular piece of regular white paper, slightly smaller than the circular printed sticker, was first glued on the base. It had no other marking than a handwritten inventory number, in the same script as the later one. Usually, this sticker is almost completely hidden by the posterior printed label, but in many cases its corners protrude from under the circle, proving its anteriority. It also appears to be completely missing from many items still keeping their circular label, presumably because it was removed first. That this sticker bore an inventory number too is manifest on the very rare specimens where it was neither covered nor removed, such as the small Acer negundo vase pictured above. The lack of any other indication, printed or otherwise, like the high value of the written number on many of these, allow ruling out that it belonged to a retailer or that it could have any other function.

The emerging picture from these observations is that the glass pieces were numbered twice: first, at their entry in the factory general stock inventory, on the simple rectangular sticker, and second at their exit to fill in some order, on the round printed label. The problem here is that nothing is known about the first count: when did it begin? Was it ever reset? The sample is far too small to get some proper answers. The simplest hypothesis is that this number reflects the count of made pieces over one definite period of time. In that sense, it’s different from the number on the printed label, which, as Albert Daigueperce’s testimony demonstrated, is a shipping lot number, comprising one or several (sometimes dozens or hundreds) items from the same series. As we’ll see in the second part of this study, this seems verified by the Acer negundo vase bearing both labels, and from other close specimens.

The existence of this first count and labelling of the pieces in the factory is essential too because it explains why there could have been several shipping labels in use during the same period, most notably some with a lot’s number and some without, and why some pieces might never have had any such secondary label. It also helps to confirm Daigueperce’s indication that there was a specific lot count for the Paris depot (which ran up to 91,500 under his stewardship, as we’ve seen), rather than a general count for all the shipped lots.

The 1912 reconciliation inventory from the Paris depot and the labelling system.

In this view, the primary (sole ?) function of the printed labels bearing a handwritten number was to help to track the shipments from the factory to the depots during the annual inventory reconciliation process. Thanks to the preservation of one such inventory list (the 1912 one), from the Paris depot, it’s possible to reconstruct this process. This document is a small ledger comprising several lists compiled in Nancy, by comparison between the Paris depot end of year inventory and the factory sales or shipment books. The first version of the document includes four lists:

A first list (A) details the “missing pieces”, presumably items that did not show up in the Paris initial inventory despite being listed as shipped from Nancy. This list A was annotated by Albert Daigueperce himself (it’s from his handwriting) with the addition of the buyers’ names.

A second much shorter list (B) is titled “excess numbers”: it contains extra items showing in the Paris initial inventory but listed in Nancy as having been already sold. Again, Daigueperce’s annotations give some explanation regarding these discrepancies.

A third list (C) assigns new lot numbers to some objects which did not already have one because they were part of the Galliéra museum exhibition in 1910-1911 and left as a depot there.

Finally, a fourth list (D) gives new lots numbers to merchandise which missed one. It’s not completely certain if these items were also part of the Galliéra depot, but it seems so.

Daigueperce did return these lists with some explanations on the 2nd February 1913 and received on the day after (3rd Feb.) the revised version with a new list appended, detailing the recipients’ names for all the orders still in question. He answered on the same day and was sent, on the 5th February, a new expanded version of the document, with yet another new list of their differences. Another final exchange took place and the definite answer from Nancy was dated from the 12th February. It took therefore four mailings from Nancy to Paris to reconcile the differences between the two sets of inventories. The various iterations of the document were enriched in the process with a trove of new information regarding the marketing practices of Établissements Gallé and the identity of their retailers.

What is of interest for the matter at hand is the proof that some items could be shipped from Nancy without a lot’s number, since the corrective lists C and D specifically aim to assign them one. And it makes sense too because they were not shipped to the depot to fulfil an order, but directly to the Galliéra museum for an exhibition – or, perhaps, to the depot but in a separate packaging indicating their final destination. But once they were transferred to the depot, they had to receive a number, and hence the addition made to the reconciliation inventory.

From this observation, one can infer that the numbered labels were probably specific to the depots, that is to the shipments made to Paris, Frankfurt and London, and that the direct orders to the factory, as well as the orders, made through the traveling salesmen, did not have one because there was no distant stock inventory implicated in these two categories. They nevertheless accounted for one third of the sales, according to the general table of revenues for the 1901-1913 period.

This still leaves the problem of the competing depots, mainly Paris and Frankfurt, and the way their shipments were differentiated or not. The working assumption at this point is that at least two running series of lot numbers coexisted, one for each, and that both used the same labels, despite the source of confusion it might have been. The ultimate validation of this hypothesis would be to find a match between a lot’s number in the 1912 inventory reconciliation lists and a numbered label: that’s a goal that has remained elusive so far.

In a second part of this essay, I will lay out the dating system these labels allow, in a precise enough way for the duration of the Daigueperce stewardship in Paris, and in a more speculative manner for the 1920s and 1930s.

(to be continued)

© Samuel Provost, 25 May 2021.

Footnotes

Le Tacon 1998, p. 192.

Olland 2016, p. 159.

I made some preliminary remarks about it while discussing the Mk IV and V signatures and I plan to return to the subject in an article about the Gallé export to the USA.

See for instance numerous examples in the Gallé line 2013 catalogue, cat. 91, 106, 108, 338, 350. Retailers did likewise : ibidem, cat. 106, 107.

Klesse B. et Mayr H. 1981, Glas vom Jugendstil bis heute: Sammlung Gertrud und Dr. Karl Funke-Kaiser, Cologne, König, cat. 160, p. 241 and p. 57 for the signature. It’s unfortunate, but quite telling regarding the interest in these details, that the picture taken of the signature for the catalogue truncates the label.

Gallé line 2013, cat. 338 and 350.

Garner Ph. Gallé, Flammarion, 1977.

Hartmann 1997, cat. 7177 and 7178, p. 320.

Respectively from Heritage Auctions, 2010-05-26 #69320, and Adjug’Art in Brest, 2007-12-12 #262.

Hartmann 1997, cat. 6183 ; Olland 2015, table 14 p. 159.

Rhododendrons relief vase, Mk VI signed, ca. 1925-1936, Pierre Bergé & Associés, 2007-11-23 #515. The same vase was later sold by James D. Julia.

Hutchinson Scott 2021-03-06.

Bibliography

Gallé line 2013: Линии Галле, Европейское и русское цветное многослойное стекло конца XIX — начала XX века в собраниях музеев России, Moscow, 2013.

Hartmann C. 1997, Glasmarken-Lexikon 1600-1945: Signaturen, Fabrik- und Handelsmarken : Europa und Nordamerika, Stuttgart, Arnoldsche.

Le Tacon F. 1998, L’œuvre de verre d’Émile Gallé, Paris, Éd. Messene.

Olland Ph. 2016, Dictionnaire des maîtres verriers, marques et signatures : de l’Art nouveau à l’Art déco, Dijon, Éditions Faton, p. 159.

How to cite this article : Samuel Provost, “Understanding Gallé Labels (I) : the different types”, Newsletter on Art Nouveau Craftwork & Industry, no 12, 25 May 2021 [link].