Mismatched lamps and later ‘marriage’ of parts from the Établissements Gallé

A note on the division of labour and serial production issues

In a previous paper, regarding the identification of Jean Rouppert as the main designer of Établissements Gallé lamps in the early 1920s, I briefly touched upon the subject of differing signatures on the shade and base from the same specimen. The Ivy lamp which spurred that study featured such a disparity, that I dismissed at the time as inconsequential, given the object’s other characteristics. A later pairing of two parts from different production runs of this series looked all the more improbable because another specimen sported the same two signatures.

This is nonetheless a recurring concern among Gallé collectors, for several reasons, all stemming from the fact that such later pairings are not uncommon in lamps: they fell under the broader designation, in trade speak, of ‘marriages’ of parts, when unscrupulous actors assemble unrelated parts to make an object whole in appearance, and sometimes even to create a new chimera-like one. This practice has been well documented by various authors: Tiny Esveld devoted an entire chapter on this practice in her glass collecting manual.1 Victor Arwas once commented that repurposing some Frères Muller lamp’s caps to complete damaged Gallé ones was so common that it made original Muller lamps sparse and led in turn to an increase in their market value. Schneider’s Le Verre Français was another glassmaker whose products were frequently used in this way.2

The shape and function of the so-called ‘mushroom’-shaped lamps make them prone to breakage, especially when their foot has a narrow tube-like or spindle-like form. Their top-heavy design, in most cases, makes them easy to topple accidentally. Electrical cords can be tripped over, the stress from the metal parts can damage the glass in the long run (see above), etc. Looking for a replacement shade or foot for a damaged one is therefore a regular endeavour for lamps’ collectors and sellers, with no guaranteed success, in particular for rare series – which explains why some are sold in various states of disrepair, as seen in the example above, before and after being retrofitted. When a spare part with a matching decor pattern is found, however, signatures can be different: the question then arises if this disparity can serve as a hint (among others) that the lamp is not in its pristine original self, but that it is such a ‘marriage’. The answer is negative, as stated before and as shown, for instance, in the Strasbourg city landscape lamp highlighted above: there’s no doubt that the two parts belonged to the same original lamp, despite their mismatched signatures and the contemporary repairs. The matter nonetheless deserves a more thorough explanation, involving a look at the few pieces of information available on this particular line of products in the Gallé factory.

Lamp making in the Gallé factory

Not much is known about the lamp manufacturing process in the Gallé factory. As I’ve noted before, in the article about the Cylène series, these were late additions to the Gallé line of products, with Émile Gallé devoting a substantial effort to develop them on an industrial scale from 1902 only. Some notes in the Charpentier files, taken from the Gallé-Daigueperce correspondence, give a few more details. As Henriette Gallé reminded Albert Daigueperce, the depot manager in Paris, in a letter from September 1907,3 it was he who asked for the lamp mounts and electrical wiring to be made in house, despite their low profit margin, especially compared to the complexity this added to the manufacturing process. Daigueperce, who had initially accepted a lower percentage (5%) as his sales commission for the electrical products, was asking for a 5% percentage raise, because of the trouble he was experiencing with them. Henriette Gallé denied his request, arguing that the factory was already assuming onerous charges as they were. This budding commercial dispute in 1907 did fester over the years until Henriette Gallé’s successor, Paul Perdrizet, fired Albert Daigueperce in 1920.

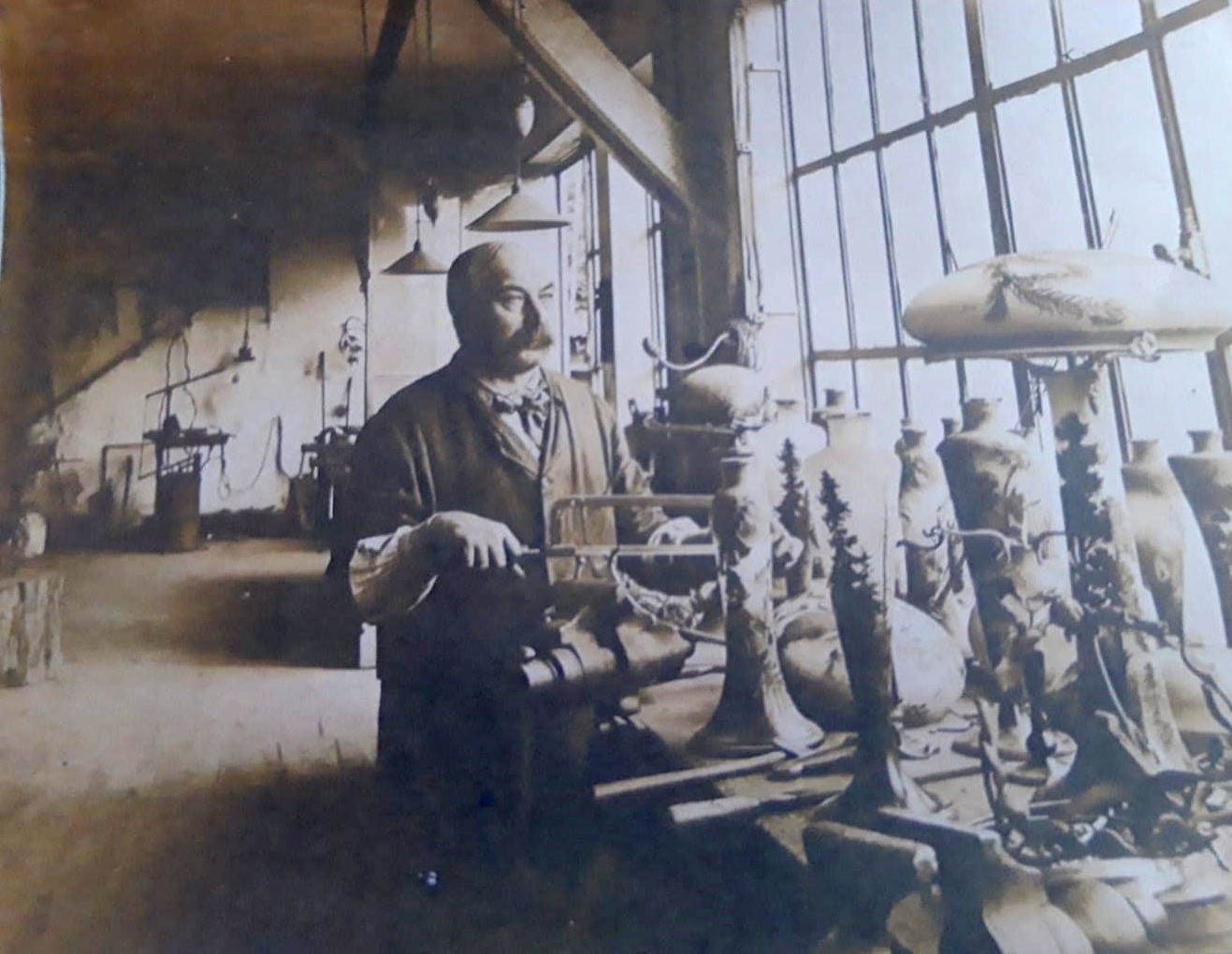

In the early 1900s, Émile Gallé presumably had to expand his small metal-working and locksmith team to accommodate this new task. To my knowledge, there remains but one picture of this workshop4, from a later period, which suggests it remained a small and basic operation. The 1911 population census in Nancy lists three workers as art locksmiths and another one as a wrought iron smith. Needless to say, they also had to work for the cabinet making department.

As for the glass part, there’s no indication that the lamps parts were treated any differently than any other piece, from their blowing in wood or cast-iron moulds, to their acid-etching. The few subsisting written or oral testimonies from Gallé workers and designers (mainly by Dézavelle and Rouppert) do not address that matter. When the decorator René Dézavelle mentions lamps, it’s only to discuss some particular decor pattern, presumably some series he worked on, in the 1920s.5 Lamps are not considered as a separate category in the few archives left from the factory, be it on the accounting books from the depot in Paris (despite their lower sales commission), or on the few lists of objects remaining – the factory inventories of 1904 and 1925, the reconciliation list of 1912, the final inventory of the depot under Daigueperce in 1920. In each case, the lighting fixtures are listed among a jumble of items, without any apparent order. Up to the point when they received their metal mount and electrical wiring, the glass parts of the lamps were streamlined with every other object made by the glasswork at the time.

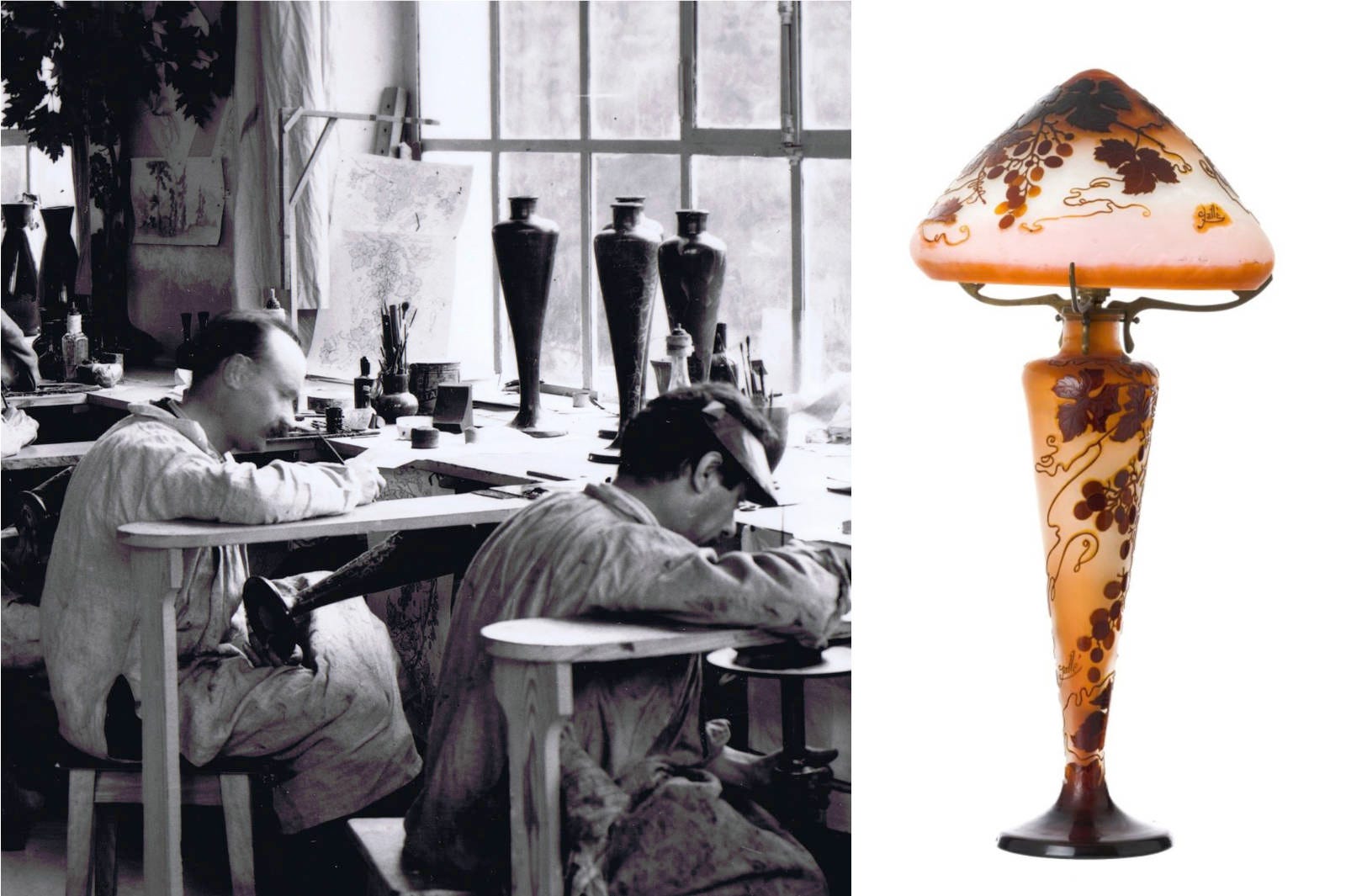

Photographs from the various workshops inside the factory confirm this observation. The decorators’ workshop, the polishing, and the cutters’ shop have rows of lamp feet and stacks of shades mixed with vases of all size and shapes neatly lined up on the worktables. More importantly, bases and shades do not even look to be strictly grouped together, to facilitate their later pairing and assembly. What the pictures suggest is that, as for any other glass items, lamps were blown in small batches of roughly 12 to 30 copies6 and brought to the successive workshops where they received their decor. There was no pairing of a particular hat with a specific foot because each model was made in multiple copies and each one of them was supposed to be interchangeable7 – and they almost completely are, to the untrained eye. On a picture of the men decorators workshop, taken in late 1912, for instance, a stack of at least 14 lamp hats (I would venture that they belong to the black and red/orange landscapes series, with a flight of swallows8) stand on a different table than the feet, that look to be a few feet away; two Grapes-decorated shades are alone on the lower shelf on the right, while the corresponding feet can be perhaps distinguished behind the standing man on the left.

One should also note that no existing marks point to a numbering system allowing to match a particular foot to a specific lampshade, in contrast with some number pairing between perfume flasks and their stopper.

The product serial uniformity was achieved by the general quality control in the workshop, but also, probably, by trusting these small batches to the same small team, or even to the same painter. Another photograph from the same Gallé workshop shows a decorator painting a tall Grapes lamp-stand – the pattern is easy to identify from two drawings, one pinned to his workbench, the other put up against the window, for the benefit of the next worker to his left side. Four other lamp feet await on his table, in front of him, having already received the protective varnish, it seems, from the discernible pattern. Finished or still to be worked on, these lamp feet confirm that the same decorator was painting a batch of identical items, which of course makes perfect sense, to ensure the maximum consistency in their appearance. The corresponding hats are nowhere to be seen in this picture, but they were being worked on at the same time, as the previous picture we discussed, taken on the same occasion, suggests. Neither of the painter’s immediate co-workers, on his left and right side, looks to be decorating lamps’ parts, but other shapes with the same pattern.

The evidence from the Ateliers des graveurs réunis

One possibility left opened by these pictures is that the painter worked successive series of matching bases and shades, allowing the same hand to decorate both parts of the lamps. In this regard, the archives of the Société des graveurs réunis, Paul Nicolas’ outfit after his departure from the Établissements Gallé in 1919, hold some interesting information.9 When they founded their Art glass company, Paul Nicolas and his associates replicated in almost every aspect the workshop’s organisation they had known for decades in the Gallé company. They worked in large part with the same material and the same techniques. One can then assume with some degree of confidence that their practices reflected Gallé’s ones. Among their archives, one notebook is of particular interest in this case, the manufacturing register: it records for 1919-192010 each decorator’s work, listing by reference number, shape number, sometimes height, the various series he or she was given, their decor designation, the number of copies made, the work hours total spent on each series, and finally the corresponding payment he or she received, with the date and his or her signature. This is a fascinating document, albeit often an incomplete one (not all information were properly entered for each glass series): it gives a valuable insight on the inner workings of the association, and it allows identifying and date with precision some glass series, among other information. For the matter discussed in this paper, this register shows that, in the Graveurs réunis’ workshop, the same decorator was entrusted small batches of bases and then of corresponding hats (they called reflectors) to work on.

For instance, in February 1920, Roger Guy, one of the associates, painted 2 different lamp series with the same Raisin (Grapes) pattern, in 7 batches in a row, alternating between feet and bases, for a total of 47 lamp feet and 64 reflectors over a little more than two weeks:

He began with 16 feet from the model referenced 354 (shape number 283, priced Fr 2.75 apiece), then did 17 reflectors (same references, priced Fr 3.50), before moving on to another identical batch (16 feet, 17 reflectors) from the same series (or is it a second tone on the same batch ?).

He then worked on a different shape (61N), under the 350 reference number, presumably a much taller one (priced higher than the first, with Fr 6.50 and Fr 6.00 for the foot and shade respectively), for which he did three batches, two set of 15 feet, separated by one set of 15 reflectors.

Then, he moved to a different pattern, Vigne vierge, reference number 352, with yet another shape (number 66N), of which he painted 15 feet and 14 reflectors (priced Fr 4.25 and 3.50) in 4 batches, thus repeating the pattern set with the Raisin series.

The number of worked hours is sketchy, but he was apparently allotted 30 hours for each combined batch of 16/17 feet and hats, so a little under one hour per part. This will need a complete analysis of its own, but these numbers look to align with those known from Rouppert for the Gallé factory in 1913-1914.

So, to sum up, in the Graveurs réunis workshop, a decorator was working full-time on lamps with the same pattern, alternating between batches of feet and hats, for several weeks in a row, and then switching to a different shape and/or pattern. The size of these batches was roughly the same as what one can see in the Gallé factory’s photographs, 15 to 20 items. The number of reflectors made for a given base could be higher, and significantly so in the case of the nr 350/61N Raisins lamp, but it was by no mean a general rule. Other examples from the register show sometimes a complete disconnect between the number of feet and hats made by a decorator.11 This all but confirms that there was no pairing, at this stage of the manufacturing process, of a specific specimen of a base with a specific lampshade. But, this also insured a better consistency in the decor’s quality, since the same hand was responsible for both parts and got better at it with the repetition of the task.

One could argue of course that the size of the Nicolas workshop was much smaller than the Gallé one, and that a larger workforce permitted a more detailed division of labour: one decorator might have been tasked with painting the lamps’ feet, while another one was doing their hats. The photographic evidence from inside the workshop, as we’ve seen, lends some credibility to this hypothesis, without ruling out the possibility of the same organisation as in the Nicolas’ team, where one decorator was working his way through successive batches of hats and feet.

This could, in fact, explain some cases of discrepancy between the signatures on some lamps: different workers using different stencils of signatures to mark the batch of pieces they were working on. This solution, however, isn’t satisfactory. Consistency in the use of signatures on the same series at the same time looked to be a tenet of Établissements Gallé’s practice after 1904, to set these marks as an authentication tool. At the minimum, to have the same signature on the different parts of a lamp was a desirable requirement, to avoid confusing clients. It’s well known from oral testimony of former Gallé workers that one of the foreman’s job was precisely to check on the signature’s existence on each piece, and presumably to ensure that a correct stencil was used to draw this signature on all but the smallest items where it was freely draught by hand.12 It would therefore be strange that the decorators’ foreman would allow the concurrent use of different marks on the same series. One could envision some specific reason, like the preparation of a special retail order, where the client had requested such a distinctive mark, but there is no trace of such a case in the bits of information at our disposal. The most straightforward conclusion therefore remains that, at a given time, the same mark was applied to one series, and in the case of lamps, to its different parts.

Lamp pairing in the packing room: the evidence from wartime.

During the First World War, a crucial source on the factory’s inner workings emerges with the correspondence between Paul Perdrizet, the de facto director of the Établissements Gallé, then mobilised in Paris, and his wife, Lucile Perdrizet-Gallé. She was making regular trips back to Nancy to see her sister Claude, still living there, and she was relaying her husband’s instructions to the factory’s director, Émile Lang, as well as gathering information on the state of the family business. In April 1916, a little more than a year after the Établissements Gallé had resumed their operations, despite the lack of a functioning fusion furnace, with a bare-bones crew, the stock of merchandise was running low. Concerned about the lamps, Paul Perdrizet repeatedly inquired about the possibility to replace missing or insufficient lampshades by using silk shades, and asked the orphan lamp bases to be sent to the Paris depot. His wife answered that Lang still managed to find matching parts, and that he was reluctant to send to Paris some lamps for which he felt he could still find a hat.13 Two months later, in August 1916, she was reporting that there were remaining quite a few lamps with shades.14 The silk shade solution was a desperate measure, reflecting the shortage of spare parts in a difficult situation. But, the anecdote also underlines that the pairing of lamp parts was in all probability always made in the packing room rather than in the decor workshops, or even in the mount fitting one. That the factory’s director was looking himself for matches was of course exceptional, a consequence of the lack of personnel in this time of war, but we should assume that the task was normally undertaken by the packing department’s employees.

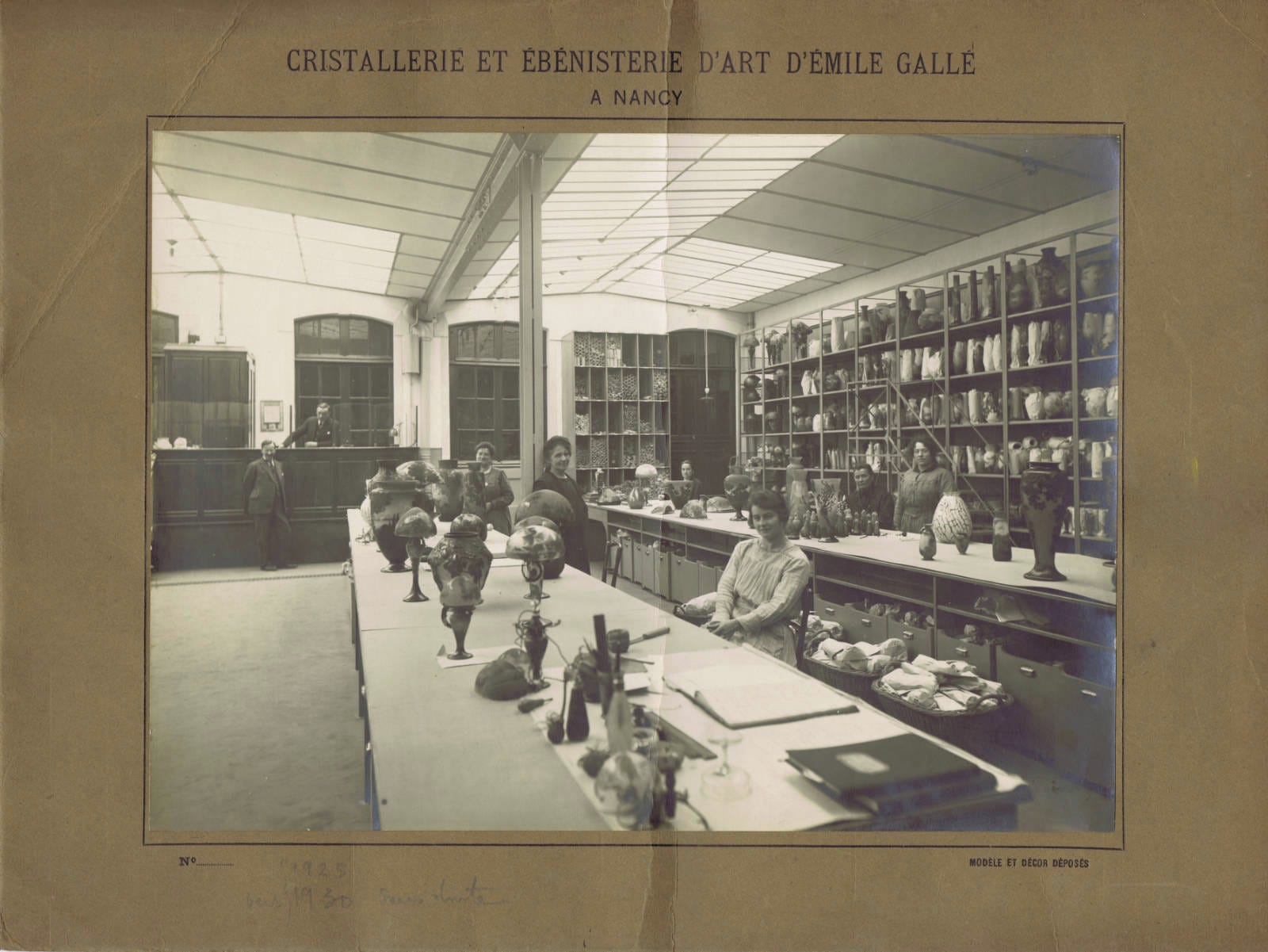

Very little is known about this part of the Gallé operation, which was under the supervision of one Eugène Rousselot. Two photographs from 1927 show a vast room, adjacent to the exhibition hall, and whose walls are lined up with wood racks stacked with glass (see above). Worktables are laden with vases and lamps, most of them obviously showcased for the special occasion that was this photographic session. It is striking how few lamps are visible, compared to the hundreds (thousands?) of glass pieces shown. More importantly, there are no stacks of lampshades nor rows of lamp feet awaiting to be paired on the shelves. It should be noted, though, that one side of this room remains unseen, and with it perhaps more glass shelves, as well as other locals – for instance, the photographs do not show the straw-filled crates used to ship the merchandise. So, as with all such pictures, one should be weary not to extrapolate too much from what little is shown, especially given that these photographs were taken as advertisements for the factory, with a careful composition, and much attention given to what could be pictured or not.

In normal times, there were always more lampshades than feet made, if only because some of them were used alone, as ceiling fixtures, or in lamps designs with metallic (bronze or wrought iron) bases, even in the 1920s, as the 1927 sales catalogue does attest. Some shades could also be sold to retailers who fitted them on their own more ornate bases, as it was visibly the case in the early 1900s, with the Meliodon lamps. Finally, some could be kept as spare parts.

So, there was no need to match a base with a lampshade too early in the manufacturing process. It made sense, to speed up the production, to group identical parts in batches in the decor workshop and to let the pairing happen in the packing room or in the mount making one. One of the consequences was that parts featuring different signatures were then paired because the priority was given to the consistency of their decor pattern over that of their mark.

© Samuel Provost, 28 October 2024.

Bibliography

Arwas, V. 1987, Glass Art Nouveau to Art Deco, Londres, Academy Editions.

Dézavelle, R. 1974, L’histoire des vases Gallé (The history of the Gallé vases), Montréal, 1974 (Glasfax Newsletter).

Duncan A. and De Bartha G. 2013, Gallé Lamps, Woodbridge, Antique Collectors’ Club Ltd.

Esveld, T. 2010, Glass made transparent: a practical guide to French art glass by Gallé, Daum and Schneider, Rijkevorsel, Belgique, Gallery Tiny Esveld.

Le Tacon, Fr. 1993, “Les techniques et les marques sur verre des Établissements Gallé après 1918”, Le Pays Lorrain, 74, 4, p. 203‑218.

How to cite this article : Samuel Provost, “Mismatched lamps and later ‘marriage’ of parts from the Établissements Gallé. A short note on the division of labour and serial production issues”, Newsletter on Art Nouveau Craftwork & Industry, no 29, 28 October 2024 [link].

Footnotes

Esveld 2010, p. 130-137, in particular p. 135 for an Établissements Gallé lamp.

Arwas 1987, p. 18-20.

Letter from Henriette Gallé to Albert Daigueperce, September 1907 (as quoted in Françoise-Thérèse Charpentier research notes): “C’est sur votre demande que nous avons fait des montures à nos lampes (faible bénéfice, etc.). Je reconnais volontiers que l’article éclairage nous donne quelques peines de plus que la vente d’un vase ou d’une petite table, mais nous rencontrons les mêmes difficultés et avons moindre bénéfice.”

The picture above is a digital copy of the photograph that Philippe Wingerter posted on the French Art Glass group, on the 02.08.2021: I thank him for bringing it to my attention.

Dézavelle 1974, p. 45-51, with a bad sketch of an Ombelles lamp.

These are the numbers given by R. Dézavelle, that are consistent with what the pictures show: Dézavelle 1974, p. 27.

See the exasperated remarks from Jean Rouppert on this, despairing on the lack of variation and the tyranny of uniformity in the Gallé factory, from a decorator’s point of view: Provost 2018.

From its shape, sparse decor partter, and the Rouppert testimony to the presence of this series in the workshop in July 1913.

The archives were donated by Florence Nicolas to the city archives of Remiremont.

With the earliest work recorded in September 1919, this should be the first register in the company’s run. Unfortunately, later ones do not seem to have been preserved.

For instance, in December 1919, one Anxionnat made 3 big Raisins lamp feet, and 6 matching (presumably) large reflectors, but also 1 small one, whose stand he hadn’t done. He is perhaps the Maurice Anxionnat attested as a Gallé worker in 1911 and 1931 on the Nancy population registry. In that case, he would have been part of the team leaving the Établissements Gallé with Nicolas in the 1919 summer, only to return a few years later.

Le Tacon 1993, p. 214.

Letters from Lucile Perdrizet to Paul Perdrizet, 15 and 19 April 1916, Gallé family archives.

Letter from Lucile Perdrizet to Paul Perdrizet, 2nd August 1916, Gallé family archives.

Samuel, I’ve always loved lamps and now I think I’ll love them even more. Such great history and background on these pieces. Thanks for sharing.