A Fateful summer: New documents on Émile Gallé’s last months.

Three letters from Émile Lang, the director of the Gallé factory, July-September 1904.

While researching the various Gallé labels, I came across a specimen of the well-known Emile Gallé • Nancy Paris type (E5 in my classification) in a quite unexpected place: it had been used as a makeshift seal on a private message from Émile Lang, the acting director of the Gallé factory, to Albert Daigueperce, the manager of the Paris depot. I will publish later the second part of this research on Gallé labels, but, in the meantime, I felt this letter, as well as two others from the same correspondence in the Daigueperce files, were worth publishing, because of the light they help to shed on Émile Gallé’s last months. The underlying questions they help to elucidate is how much work Émile Gallé was able to do in his last year, while severely ill, and how autonomous was the functioning of the factory in his absence.

This short letter is seemingly dated from July 1904 (see the explanations below for the cause of uncertainty). It thus provides both an indisputable specimen of this label’s type — the ultimatespecimen even because it was stuck on a genuine Gallé document by the factory’s acting director1— and a valuable chronological marker for its use: it antedates Émile Gallé’s death, a fact that was already known from the many specimens preserved on pre-1904 glass pieces. It also confirms, if needed, that the labels were stuck under the pieces’ base in the Nancy factory, before being shipped to the depot and the retailers. In all probability, the letter this particular specimen serves to seal, was indeed enclosed in such a shipment to Paris. That explains the lack of a stamped envelope that would have made the makeshift seal redundant. Émile Lang must have included this personal message to Albert Daigueperce in a regular package from the factory to the depot, with the shipment’s usual paperwork. But, perhaps to protect its privileged content from the prying eyes of the depot’s lesser employees2, as his demand for discretion attests in another letter, he decided to summarily close it with this label, that Daigueperce had to tear up to read the message. The information it conveyed was indeed crucial: the failing health of Émile Gallé and the growing probability of his demise, and therefore the uncertainty surrounding the fate of his company, were important matters.

This was not a formal letter. It’s not written on regular correspondence paper but on a piece of a page torn off from some kind of notebook, that was simply folded on itself to close it. On one side is written the message, reduced to its essential information (no address, no date, no identification of the writer apart from his signature) while the other bears the sole mention of his recipient, Monsieur Daigueperce, without any address either. The Gallé factory had had some formal official stationery from a long time, with a letterhead listing the various depots and reminding the bevy of honours received by its founder. But it was not used, judging from this sample, in routine exchanges between the factory and the depot, which probably received at least weekly shipments to restock its inventory as well as to fulfil the special orders it received3. As stated earlier, this message is one of three preserved in the Charpentier files, where they found their way most probably through a donation by the recipient’s only daughter, Suzanne Daigueperce in the early 1970s4. The three similar letters belong to the same series of informal written communications between the factory in Nancy and the main depot in Paris. Their size and medium are the same. They should be representative of the kind of notes the writer, Émile Lang, frequently sent to Albert Daigueperce.

The protagonists and their role in the Gallé company.

Notwithstanding its dramatic subject, the terminal illness of Émile Gallé, who died on the 23rd September 1904, at the age of 58, the interest of this exchange also stems from the fact that it comes from the seldom heard voices of these employees. First-hand testimonies on Gallé’s failing health in his last years have been available from a long time, but they emanated from his letters to his friends or to family members, like his wife and daughters. For the first time, original, albeit tantalising short documents, show how some main characters in the Gallé operation reacted to this tragic development in the summer of 1904.

Émile Lang (1865-1949), acting manager of the factory.

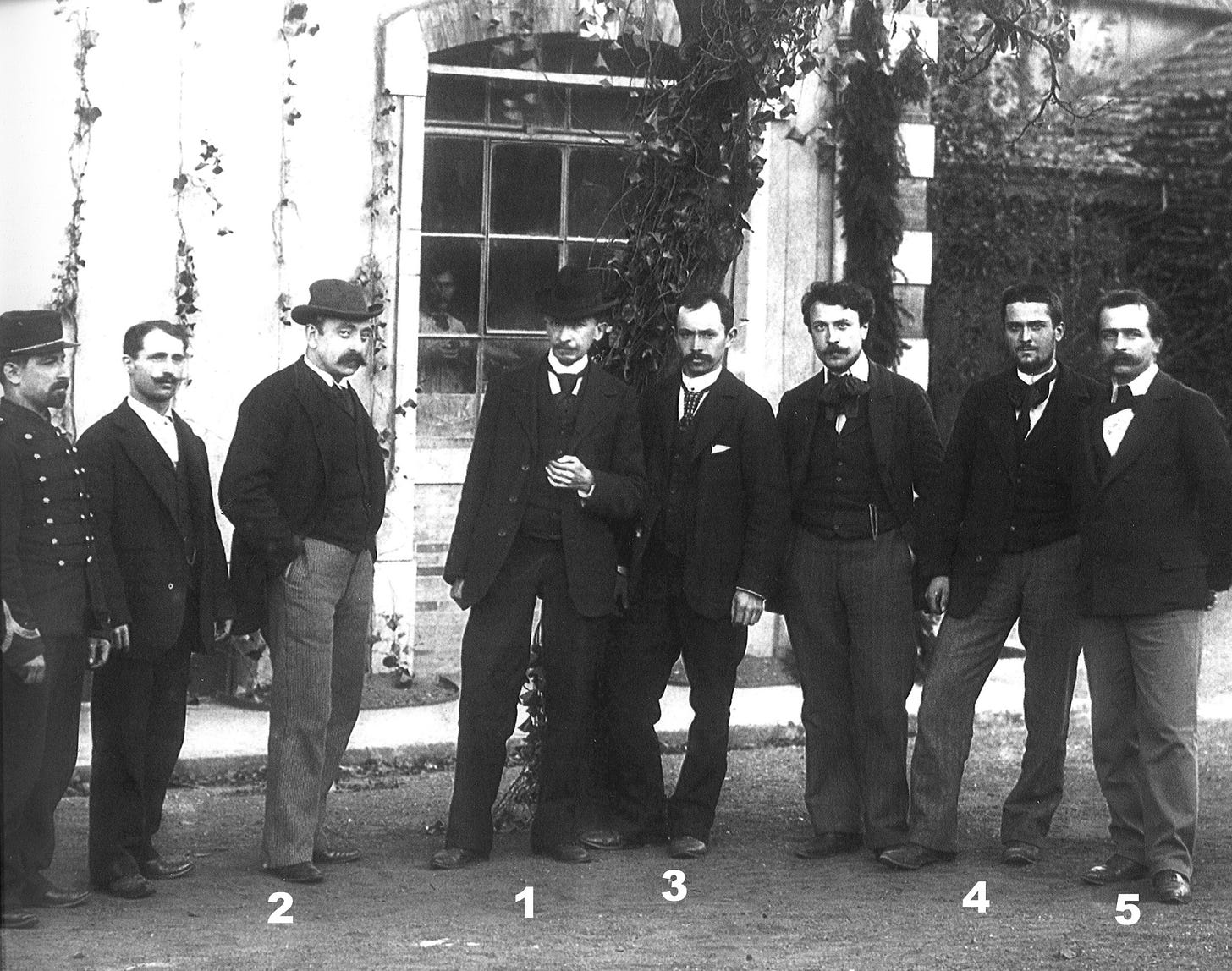

The author of the letters, Émile Lang, was the trusted right hand of Émile Gallé for every logistic and technical aspect of his operation. On the famous group photograph of Émile Gallé and his closest collaborators, Émile Lang stands the closest to the master, next to his right, shoulder against shoulder. Named after his father, a wheel cutter for Gallé, Émile Lang joined him in 1878 and worked his way up as a glassblower until becoming responsible for the hot work (glassblowing) hall, after Joseph Burgun’s departure ca. 18955. Shortly after the 1900 Exposition universelle, where he had been awarded a bronze medal in the Cristaux et Verreries class, Émile Gallé trusted him with the supervision of all the glassmaking operation. Given the importance of this department in the Gallé company, and Émile Gallé’s increasing absence from the daily operations, he could be considered as the acting manager, especially after Daniel Schœn, named as the official director in 1897, left the company in 1901 to pursue a career as a painter and art professor6. The correspondence between Émile and Henriette Gallé makes abundantly clear that Émile Lang was in charge of most of the administrative and technical matters, from paying the workers’ wages to supervising the workshops or the fulfilling of orders, and so on7. After Émile Gallé’s death, he officially took the title of director of the factory and kept it until its final closure in 1936. In 1930, he was awarded the Légion d’honneur for this role8.

Émile Lang was therefore the primary correspondent in all administrative and commercial exchanges between the factory and the Paris depot. It’s no surprise to see him taking the initiative of keeping Albert Daigueperce informed.

Albert Daigueperce (1873-1966), manager of the Paris depot.

Albert Daigueperce succeeded his father Marcellin, on his death in 1896, as the manager of the main Gallé depot, on the Richer street in Paris, after having worked under him from Gallé since the 1889 Exposition universelle. At such a young age (he was 23 years old), he inherited a massive responsibility, since the depot accounted for roughly half the sales of Gallé. But he was up to the task, and he played a crucial role in the next decades steering in part the commercial aspect of the company and acting as an adviser, passing on the main clients’ and collectors’ requests to the factory. Albert Daigueperce was awarded a silver medal in the 1900 Exposition universelle as Émile Gallé, while underlining his youth9, recognised early on his role10. After Gallé’s death, the relationship gradually soured with the family, first under the direction of Henriette Gallé, and then of Paul Perdrizet. The latter finally dismissed Albert Daigueperce in August 1920 because he had refused to lower his 10% fees on part of the sales (the lamps).

Albert Daigueperce went on representing some glass artists, among which Paul Nicolas who had also left the Établissements Gallé11. In an announcement of the 1925 Exposition des arts décoratifs in Paris, he is even mentioned, between Daum and Marinot (no less), as a notable exhibitor in the Classe XII (glass) in the Grand Palais12. He maintained a cordial relationship with most of Gallé’s artists and collaborators, who kept him informed of the company’s affairs. He was also a preeminent member of the Chambre syndicale de la céramique et de la verrerie, the professional association overseeing the glass and earthenware industry: In the 1920s and 1930s, he served as the association’s auditor and sat in several permanent committees related to art glass, like the Commission des expositions and the Commission de protection des arts appliqués.

Albert Daigueperce enjoyed more than a good working relationship with Émile Gallé. The latter was most impressed with his young manager’s commitment to his success, but he also considered him as a friend and a “quasi brother”, as he wrote to him in a congratulatory letter for his betrothal, on the 4th March 1904 :13

Puissiez-vous trouver là la récompense de votre sagesse, de votre vie de labeur et d’honneur. Je suis votre vieil ami, patron et quasi frère bien affectueux.

Less than seven months before his death, there’s not a hint of Émile Gallé’s medical condition in this letter, nor is there in Henriette Gallé’s concurrent letter to Albert Daigueperce and his mother. That was of course not the subject, but the genuine warmth and empathy Émile Gallé’s letter exudes contributes to explain the dedication most of Gallé employees felt toward him.

(To read the full article, please subscribe)