Commemorating the war in the Vosges mountains (1915).

A hitherto unknown specimen of Gallé’s “war vases”.

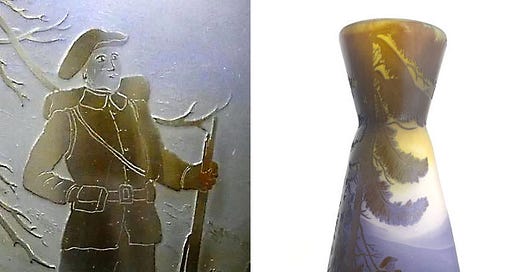

Human figures cut a very rare feature in Gallé’s glass series. Émile Gallé decided to drop human characters from his decorative repertoire as soon as the 1880s, a very few exceptions notwithstanding, turning instead to the Nature as his almost exclusive source of inspiration. Établissements Gallé stuck to this approach after their founder’s untimely demise: men or women never are the focus of the decor pattern on glass series, where they rarely appear. When they do, mostly in woodland or lake landscapes industrial series, they are always pictured as distant or secondary figures – a walker on a bridge or on a riverside, a fisherman – introducing a light human presence in the landscape, as buildings do in other ones. These human figures conspicuously lack details, often shown from the back or in shadowy profiles. In this context, a vase, sold in Albi almost exactly a year ago1, which prominently features an infantryman in a war-ravaged mountain woodland, could strike as an egregious incongruity. The auctioneer deemed it a copy, and, to his defence, the vase was part of a batch with several bad fake Gallé. There is however no reason to doubt at all its authenticity: from all technical and iconographical aspects, the vase is a hitherto unknown specimen belonging to the most rare Gallé First World War commemorative vase series. As such, its historical value alone makes it a piece worthy of a museum2.

The Établissements Gallé line of war commemorative vases was a very restricted one for many technical reasons. For one, the glass factory had shut down on the 31st July 1914, in response to France’s general mobilisation and most of Gallé’s workers were under arms. The Gallé management decided to reopen the factory partially in December 1914 or January 1915, to fill in the still standing orders from before the declaration of war. Second, apart from the lack of workers, and soon the dwindling supply of crucial materials (like the acid needed for glass etching), they had to contend with a major limitation: the main fusion furnace had been shut off in June, due to some severe malfunction, and it was beyond repairs in these new circumstances. For its glassmaking operation, the Gallé factory therefore could rely solely on small secondary ovens, unfit for making new glass series. The hot-work workshop remained therefore closed, and the few remaining glassblowers were laid off or assigned to menial tasks until 1917, when a new furnace was fired up – unfortunately with a very limited success. From January 1915 to February 1917, therefore, all new glass series made by Gallé came from their stock of glass blanks, produced in June 1914 or occasionally much earlier. This stock was, barely, enough to keep a dozen or so of painter-decorators busy. Most importantly, it follows that any new design introduced during this period had to fit existing glass blanks, both for the shape and the colour scheme, since the company stuck to acid-etched cameo glass as the exclusive technique of its product line at the time3. These factors explain the characteristics of Gallé vases from 1915-1917 and the extreme difficulty there is to identify them, to the point that their existence has been largely denied until recently: they are either undistinguishable from the 1913–1914 ones, with the same patterns on the same blanks, or they feature new decors, but they were made in small, single digit numbers, most probably on spare or borrowed blanks from other series.

The commemorative war series fall into this second category. For the glass series4, four different war themes are known until now, both from the few surviving specimens and from some allusions in the Gallé family archives:

The French cockerel towering above a vanquished German imperial eagle, i.e., a general allegory of French victories against the German armies.

The German imperial eagle embattled in Lorraine’s thistles, sometimes with the Nancy/Lorraine’s dukedom motto, “Qui s’y frotte s’y pique”, i.e., an allegorical celebration of the Grand Couronné French victory in September 1914, the successful defence of Nancy against the German army – the most common of the main types of war designs.

The Reims cathedral engulfed in flames with the motto “Heure viendra qui tout paiera”, i.e., a call to remember and to avenge the destruction of the cathedral (and by extension of French cities) by the German artillery in September 1914.

A French infantryman keeping watch over a war-scarred mountainous woodland, with makeshift graves in the background, or the commemoration of the hard-fought defence of the Vosges mountains, the natural frontier between Alsace and Lorraine, in 1915. The vase discussed here belongs to this latter category, probably the rarest of the four.

One should add a special category for some small decorative glass panels, a rarity in Établissements Gallé’s production, but quite similar to some of Gruber’s works. A handful of these panels appear to be derivative works from one of the main categories listed above, with a ruined village (reminiscing the back of the Reims cathedral vases) or a broken forest landscape (akin to the Vosges battle landscape), signed and dated from 1915.

None of these designs survive in more than half a dozen copies, it seems. All of them are acid-etched two or three layers-cameo glass, and they almost always come in different shapes and colour combinations, sometimes in a few copies, like the dark blue Eagle and thistles (3 known specimens), with the exceptions of the Reims cathedral one (3 copies or more of the same shape and colour combination) and maybe the Cockerel and eagle fight (2 known specimens). All of them feature a Mk III Gallé signature, usually an intaglio one, in accordance with the type in use during the war. The vase discussed here belongs to the fourth category, whose only published example so far was part of the 2014 small exhibition in the Musée de l’École de Nancy. And here again, while the theme and the general design are the same, their shape, and colours would make them an entirely distinct series in another context.

The new specimen of the Vosges battle-themed vase has a well attested shape in the Gallé line. It was in production at least from the 1910s to the 1920s, and it constantly remained in use. It was made in several sizes, too. As a testimony of its popularity and availability perhaps, it’s the only shape, as far as can be determined, among these rare WW1 series, to receive different commemorative decors, since it’s also the shape known for the Reims cathedral vases. The Vosges battle vase came from a different batch, though, from the Reims ones. The latter is a three layers brown-orange-yellow series, most probably derived from either brown landscapes’ or grapevines’ blanks, while the former is a three layers brown-violet-yellow one. The colour combination on this latest Vosges battle vase comes as no surprise, since it was the prevalent one on mountain landscape vases before 1914 – and it remained so after WW1. It’s nonetheless an interesting data point, since the only specimen previously known with this theme featured an altogether different colour scheme (blue-yellow).

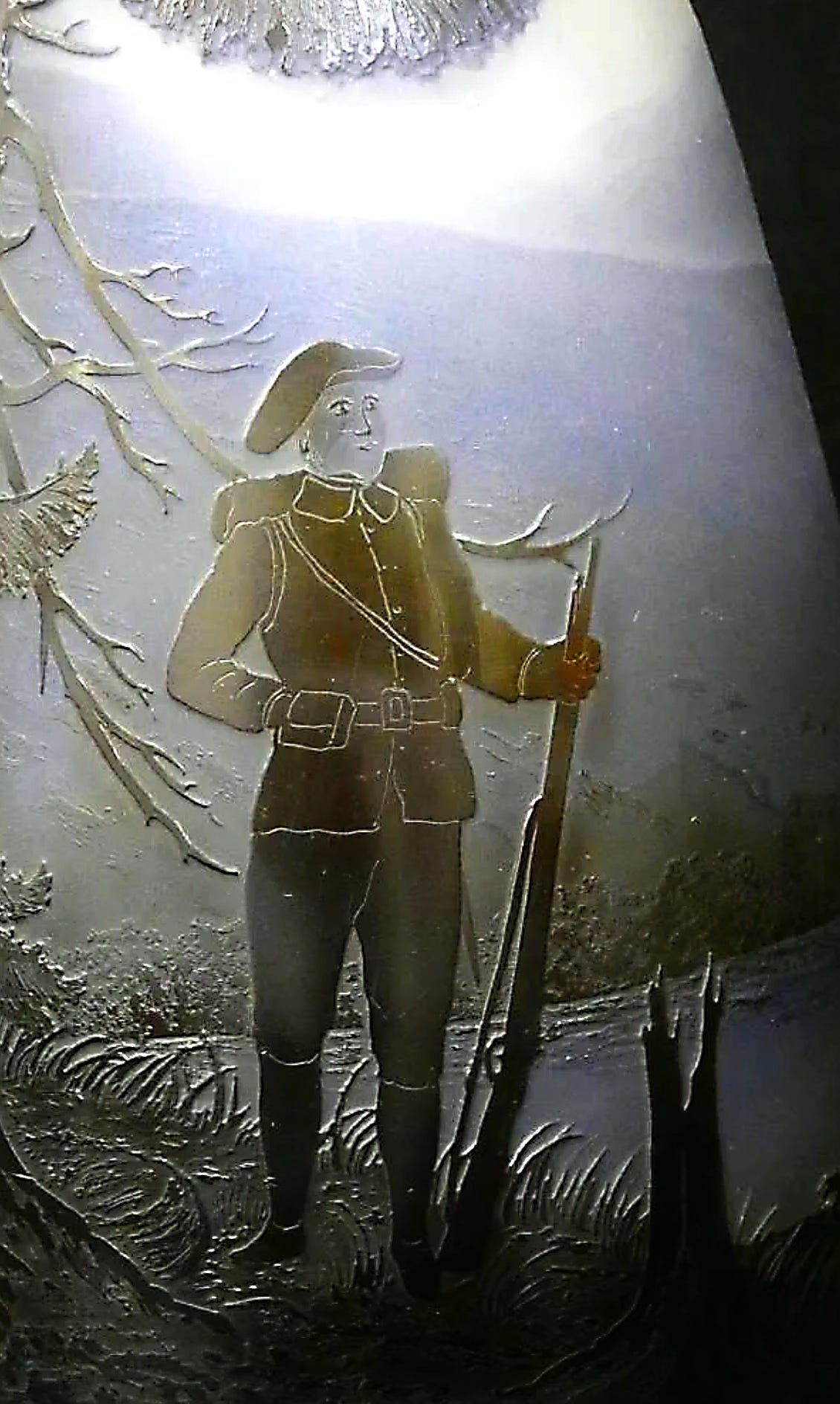

Émile Nicolas’ review of the 1915 Gallé exhibition in Nancy.

The primary source on the Gallé war-themed glass series is an important article by Émile Nicolas, published in the daily newspaper L’Étoile de l’Est on the 8th August 1915. Émile Nicolas (1872-1940) was a prominent art critic and a promoter of the École de Nancy movement, whose main artists he personally knew quite well5. He was, in fact, the brother of Paul Nicolas, one of the main designers in the Établissements Gallé, and an significant glass artist in his own right, the founder of a small glass studio in Nancy. Under the title “Sur quelques vases de guerre créés par les collaborateurs d’Émile Gallé”, the article is a review of a small exhibition held in the historic Gallé store in rue de la Faïencerie in Nancy.

This retail shop was the original family business and home of Émile Gallé’s parents, before the building of the big town house and the factory in Avenue de la Garenne, in the expanding western suburbs of the city, beyond the railroad. Émile’s father, Charles Gallé had entrusted the Reinemer-Dannreuther, his wife’s family, with this ceramics and glass retail shop, and he had conceded them the monopoly of his company’s products in Nancy, a very profitable arrangement. By 1915, its manager was Paul Couleru, a son-in-law of the Dannreuther. However, the Gallé heirs, led by Paul Perdrizet, were keen to get back the full control of the company’s sales in Nancy: after a protracted dispute with Couleru, they ended the arrangement and put back the shop’s management under their direct authority. On the 2nd July 1915, Émile Lang, the Gallé factory’s director, could state, in a letter to Albert Daigueperce:« The Couleru business will be a good business for the factory; at last, we will be at home »6. On July 15th, 1915, Paul Couleru’s stock was bought back by the Gallé7, and they proceeded to make themselves at home, as stated by Émile Lang.

The little exhibition of the war-themed vases they displayed in the shop, less than a month later, in August, had therefore a double symbolic meaning: it was first a statement of the company’s resilience in wartime – despite all the obstacles, they were able to keep their operation running and to make new art; and second, it heralded the store’s change of management, with its return under the Gallé family.

In his review of the exhibition, Émile Nicolas describes in detail each of the four main war themes, beginning with the Vosges mountains’ war. After reminding his readers that the Établissements Gallé already had a Vosges mountain landscape series in its catalogue before the war, the famous Ligne bleue des Vosges, Émile Nicolas draws the link with the 1914–1915 battles which inspired a first series of vases:

Hélas ! bien des héros sont tombés aujourd’hui en voulant reconquérir cette chère ligne bleue des Vosges et reposent dans le calme mystérieux des grandes forêts de sapins qui sont comme des temples. Le paysage a pris un caractère plus émotionnant encore car les tombes, avec leurs croix rustiques, font naître en nous des sentiments de regret et de deuil. C’est ce que l’artiste a rendu avec une grande simplicité, dans un grand vase vers le sommet duquel montent les cimes altières des sapins. A l’orée de la forêt, planté sur un roc solide, un alpin veille, le regard tourné vers le faîte de la montagne, alors que, derrière lui, des tombes rappellent que des braves reposent ici de l’éternel sommeil. Il était difficile de faire naître une émotion plus vive avec des moyens si simples. La grande nature, qui semble indifférente aux malheurs des hommes, a besoin de très peu de chose pour paraître endeuillée. Quelques branches de ses arbres cassées et une tombe suffisent pour l’harmoniser à nos peines.8

The description fits almost perfectly the vase discussed: the hazy blue Vosges mountain line in the background, the majestic fir trees in the foreground, are the hallmarks of a classic Gallé mountain landscape, but this serene vision of Nature is scarred: broken tree limbs, torn out tree stumps, the simple wooden crosses of a makeshift cemetery on the edge of the forest, and standing above these hints of a hard fought battle, an Alpine sentinel, rifle at the ready.

The only discrepancy with Émile Nicolas’ text comes in the soldier’s position, for he is standing on grass and not on the “solid rock” mentioned by the reviewer. This detail confirms that there were several versions of this design, with slight differences. Another vase from this series is indeed known (see the picture above): it was on display in the small exhibition held by the Musée de l’École de Nancy in 2014, on the centenary of WW1’s beginning9. Only a front picture of the vase is available, but it’s enough to confirm that the design’s basics are the same, even though the shape, the colours scheme of the vase and some details are different. It’s the red-brown version of the mountain landscape (i.e., the evening/sunset one, while the blue is the morning/sunrise one), and two Alpine soldiers are pictured instead of one, but this time they are standing on a rocky platform rather than on the grassy soil of the forest.

The date of the Gallé vase.

There is therefore no doubt about the date of the vase: it’s from the spring or early summer of 1915, as part of the commemorative line of glass artwork exhibited in Nancy in August that year. It fits in the chronology of the Établissements Gallé as we can reconstruct it from the little evidence coming from the Gallé family letters: the work in the decor workshops did not start again before December 1914 or January 1915 ; by the end of May, an Eagle series was being made, presumably the Eagle battling the thistles10. It’s conceivable, but unlikely that the series was still being made later than 1915. For once, work did slow down sometime in 1916, lacking acid. Another technical restrictive factor was, of course, the fast dwindling supply of available blanks that could be used to make these series, that is, in this case, pre-1914 3-layers blanks for mountain landscapes.

More importantly, perhaps, many of the war vases bear an inscribed date, and it’s always 1914 or 1915, never later – except a rare version of La Ligne bleue des Vosges featuring the 1914-1917 date interval11. Of course, these dates refer to the event being commemorated and not to the manufacturing of the vase – but the 1914-inscribed vases depicting the Reims cathedral in flames (14 September) or celebrating the Grand Couronné victory (4-11 September) were also made around May-August 1915. No vase can be ascribed to a later event or battle of the WW1, whereas one would have expected, had this line of products been expanded, to find designs about the battle of Verdun, for instance, just to stay in Lorraine.

Of course, war in the Vosges mountains did not stop in July 1915. Even though this operation theatre was much quieter in the second half of the conflict than most, some of the most deadly battles took place in late December 1915 and early January 1916 on the Hartmannsweilerkopf, and sporadic fights continue to break out the following years in the Vosges. Nevertheless, it seems unlikely that the war-in-the-Vosges-mountains vase series relate to these rather than to the Spring of 1915 battle, as we’ll see.

A key observation comes from the soldier’s equipment: his iconic black beret does identify the army corps he belongs to, the elite mountain infantry corps called chasseurs alpins (Alpine hunters), but it doubles as a chronological marker too. For, by 1916 and the later phase of the Vosges mountains’ battle, all French troops had been finally given a protective helmet in substitution for their usual soft hat. And even the chasseurs alpins were no longer wearing the beret, which was still their only protective headgear in the Spring of 1915. One cannot rule out, of course, that the designer took some liberty with this historical fact, to pay hommage to the specific mountain infantry corps that had such a prominent role in the battle. Nonetheless, combined with what we know about the Établissements Gallé’s production of commemorative war vases, this looks like a clue that the vase in discussion here was designed before 1916, and that it was part of the same group as the ones described by Émile Nicolas in his article. In the same line of reasoning, one can also note that the depicted landscape is not a winter one, but rather a late spring or summer one (no snow on the mountain tops). Finally, as it’s been already noted, the lone cameo glass panel depicting the Vosges “blue line” does bear the 1915 date, confirming that at least part (and probably) all of these war-torn forest mountain landscapes relate to the Spring 1915 battle.

The 1915 battles in the Vosges and the Hartmannswillerkopf or Vieil-Armand.

In contrast with the three other war-themed designs on glass, the vase (like the flat panel) does not represent an allegorical battle or a destruction in progress, but its aftermath. That’s the gist of Émile Nicolas’ description, depicting the Vosges mountain forest as a temple for fallen heroes, with a sentinel watching over their tombs: the battle has passed or at least subsided. Combined with a Spring or Summer 1915 date, it offers a clue as to which part of the front it’s supposed to relate.

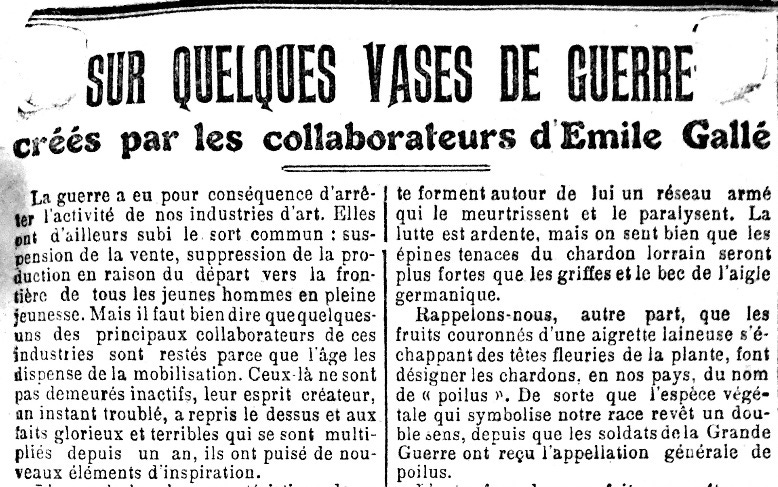

Before August 1914 and the beginning of the war, the French-German border followed closely the natural frontier that were the Vosges mountains’ summits, from the Sudel, the Ballon d’Alsace, the Bussang pass, the Drumont, the Grand Ballon, the Schlucht pass, the Bonhomme pass, etc. After some initial successes, with the symbolic reconquest of Mulhouse (birthplace of a number of Gallé’s kin) on the 8th and 19th August 1914, the French offensive in southern Alsace’s plain petered out, and the French army fell back on the Vosges’ crest. They began occupying a number of passes and peaks towering above the Alsatian plain, along the line Altkirch-Thann-Hartmannswillerkopf-Munster-Col du Linge-Col du Bonhomme (from South to North, see the left map above). This front line, established as early as September 1914, remained more or less the same for the entire duration of the war, the Vosges mountains offering such a formidable obstacle and natural fortification, making all war effort a logistical nightmare.

But as stable as it appeared, this front line was nonetheless heavily contested by the French and the German armies alike, and the theatre of some of the most deadly battles, in particular in its first phase, in 1915. The fights raged around two mountains in particular, first the Hartmannswillerkopf, and then the Lingekopf. Dubbed the Vieil-Armand in French, the first one, hereafter abridged HWK along the French practice at the time (because of its difficult pronunciation), is a rocky spur culminating at just 956 m, but with an advanced position overlooking the Colmar-Mulhouse railway line and thus deemed strategic as an artillery outpost. Beginning in December 1914, it was targeted by the Germans and then the subject of several attacks and counterattacks, culminating in March and April 1915, when the summit changed hands several times over a few days, at the cost of several thousands of lives on each side. The French press proclaimed victory and the symbolical reclamation of the HWK, with photographs of officers standing on the desolated summit (see the picture above) and triumphant articles – such as these articles on the Est Républicain, the main daily newspaper in Nancy, on 8th April “En Alsace, La reprise du Hartmannswilerkopf” and then again on the 6th May 1915, “Au Sommet de l’Hartmansviller”. But in reality, as the map of the front line over the mountain makes clear (see above), both sides remained entrenched a few hundred yards below the summit itself. While the second part of the year was quieter, combat picked up again in December 1915 and January 1916, when another bloodbath (more than 7300 French troops killed in action) resulted in little more than a tactical draw. As a result, the HWK gained the grim nickname of the “Man eating mountain”, whose slopes were littered by makeshift military cemeteries, the subject of numerous pictures and postcards, such as the ones below.

The second major battle in the Vosges, in 1915, begins on 20th July to end on the 16th October, with almost, 9000 French soldiers killed. Fought over the control of the mountain range controlling the valley of Munster, the fight is in full rage at the time of the Gallé exhibition in Nancy. It is therefore too late to have been the focus of the Gallé design.

In both battles, the Chasseurs Alpins of the Vosges Army played a major role as a shock mountain infantry corps, and suffered accordingly heavy losses. Their heroism impressed their German counterparts who dubbed them the “Schwartze Teufel”, a nickname translated as the “Diables bleus” (sic), that inspired a whole genre of patriotic tales such as the booklet by Joseph Mongis, Les Diables bleus au Vieil Armand (see the cover picture above). The Chasseurs Alpins came quickly to embody the sacrifices made in the Vosges battle, and this symbolical identification is evident on the Gallé vase.

If the French opinion in general, and the Nancy population in particular, followed with intense interest the fight over the Vosges mountains, it remains to explain why the Établissements Gallé chose to make it one of their few subjects for their war designs on glass. In the 1914 political mythology of French Revenge over the 1870 defeat, the “Vosges Blue Line” held a significant role, as the frontier of the provinces lost to the German Empire. The reconquest of these mountain ranges was therefore the first step in the reclamation of Alsace. Albeit minor in the grand scheme of the 1914-1915 battle of France, the fights in the Vosges were thus followed with a special interest. That was of course especially true in Nancy, given its status as the military capital of Eastern France and its proximity to the front: the Vosges were the playground of Nancy’s bourgeoisie, which held a high percentage of “optants”, migrants who had decided to leave occupied Alsace in 1871 and make a new life in France. Many still had family in Mulhouse or Colmar, to mention only those from Southern Alsace, like the Grimm, Émile Gallé’s family-in-law, parents that they visited by traveling through the Vosges mountain passes. Vacations or simple excursions in the Vosges mountain ranges were also a favourite for this Nancy’s bourgeoisie, at a time when such mountain tourism was developing. For Émile Gallé and his fellow artists of the École de Nancy, the Vosges, and their forests provided the nearest source of mountain flora for their inspiration. All these factors explain the creation of the very popular Vosges mountain landscapes in the Gallé glass line before the 1914.

The scene combines two pictorial types widely available at the time, in the daily illustrated press as well as in the growing number of specialised war-themed publications : one is the picture of the victorious soldiers (or more often officers) standing on the reclaimed summit of the HWK. The other is the more sombre view of the makeshift military cemeteries on the lower slopes of the French side of the mountain, where wood crosses reminded the viewer of the staggering human cost paid to retain these positions. Depending on their date, the forest shown in these photographs was more and more devastated: by June 1915, after the spring’s ferocious battles had laid waste to the woods, the mountain’s upper slopes were showing only bare charred trunks instead of trees. That is to say, the Gallé landscape is by no mean realistic – nor was it meant to be. It is certainly inspired by contemporary photographs, but it is an idealised and sanitised version of the landscape in the battle’s aftermath – for the decorative value of the glass: who would have wanted the full horror of the war pictured on a flower vase?

As it is often the case with glass artwork from the Nancy area, other glassmakers picked up on the same theme. The Muller brothers in Lunéville, in particular, made a series of mountain forest landscapes with heavily damaged trees in the forefront that may relate to the WW1 aftermath. The chronology of their making is hazy, but they are much later productions than the Gallé ones, since the Muller were not active during the war.

Attribution: A case for Louis Hestaux or Auguste Herbst as the designer?

In 1915, evidently, much of the Gallé workforce had already been enrolled in the army and only a few workers were available to design and make these commemorative series. Among the main designers, the artists who created the decors, only two remained on hand, Louis Hestaux, too old to serve and Auguste Herbst, while the third, Paul Nicolas, had been mobilised in the infantry since August 1914. Both Hestaux and Herbst are likely candidates as authors of the original decor.

The most logical hypothesis would be an attribution to Louis Hestaux, since he is known to have been the foremost designer of the war-themed series. Émile Nicolas, in his review of the 1915 exhibition, explicitly praises him as the creator of the two best known designs, the allegory of the French victory in front of Nancy (the Eagle battling the Lorraine thistles) and the destruction of the Reims cathedral. An impressive Louis Hestaux-signed war composition was acquired in 2016 by the Musée de l’École de Nancy12: a celebration of the French final victory, the drawing combines the two previous allegorical themes, with the Gallic cockerel crowing above the vanquished German eagle, while the twin towers of Reims cathedral are visible in the background – in other words, revenge has been achieved. The date 1918 prominently features in the foreground, with the same distinctive round script used for all the dates on the war series, including the Ligne bleue des Vosges glass panel. Given that Louis Hestaux was responsible for the Gallé drawing studio and the chief designer for compositions on glass, this would be a forceful case for his authorship of the Vosges mountains war series, if not for one small detail.

In his review of the 1915 exhibition, Émile Nicolas leaves anonymous the creator of this mountain landscape series, as “the artist”. Simple ignorance of the designer’s identity is most unlikely: Émile Nicolas knew everyone in the Établissements Gallé, and he was very well-informed. He makes a point of naming Hestaux for two decors, but not for the third one. This is not fortuitous; the anonymous designation is by choice and must be explained. His article’s title offers a clue of a sort, attributing the artwork to “les collaborateurs d’Émile Gallé”, plural. Besides Hestaux, this prestigious and informal title of collaborator can only be given, when it comes to the designers, to Paul Nicolas and Auguste Herbst. A reluctance by Émile Nicolas to name his brother in a glowing review – less he would have been accused of being partial, perhaps? — could explain the lack of Paul Nicolas’ name. But there is no real case for him as the unknown artist, since he was enlisted in the army on the 3 August 1914, serving in the 42nd Territorial Infantry Regiment, in the Toul and Commercy area13. In May 1915, he was employed as a military messenger (vaguemestre), but still in no capacity to supervise the making of a glass series after his composition.

This leaves Auguste Herbst as the last option. Herbst was responsible for the wood decors, not glass, in the Établissements Gallé since his recruitment by Émile Gallé in 189814. On the other hand, he is known for his multiple drawings of war scenes that were made into wood marquetry, mainly for tea trays and small ornamental wood panels, celebrating the French and British soldiers, as well as the military hospital nurses15. The drawings themselves have been lost, but they are alluded to in a letter from Auguste Herbst to Paul Perdrizet from early 1915: it looks like Auguste Herbst was at the initiative of turning a part of Gallé’s product line into war souvenirs for the soldiers and their families. In the case of the tea trays such as the ones pictured above, the authorship of this commemorative series is therefore well established. It’s logical, too, since Herbst was the foremost designer for wood decors. But one wonders if, by necessity, he was not called upon to work for some glass series too, as soon as 1915. He was certainly capable of doing it, as he showed after the war when he took over the position of chief designer for Gallé, and presided over the making of some of Gallé’s most ambitious and popular landscapes vases like the Lake of Como series. The naive drawing of the Alpine hunter on the vase is also somewhat reminiscent, in style, of the soldiers on the marquetries.

In this hypothesis, his name’s omission in Émile Nicolas’ article could perhaps be explained this way: Born in 1878, Auguste Herbst was from Alsace after its incorporation in the German Empire, with a German father and an Alsatian mother. He was thus considered as a German national by the French authorities, and, despite having fled Alsace to escape military service in the German army, he was considered a potential suspect and deported in July 1915 to a detainees camp for foreign nationals in Villefranche-de-Rouergue, in Aveyron. Paul Perdrizet did his best to prevent and then to shorten this detention, but to no avail. Auguste Herbst spent the next four years away from Nancy. This is still very much conjectural at this point, but, in August 1915, could Émile Nicolas have publicly praised an artist officially labelled a German national, and deported from Nancy barely a month before, for a design celebrating a victory over the Germans?

© Samuel Provost, 28 June 2023.

[Updated on the 21st July 2023 with the picture of the other War in the Vosges mountain vase.]

Bibliography

(collective) L’Alsace et la Grande Guerre, Revue d’Alsace, 139, 2013 [link].

Brun G. 2015, “Le front Alsace-Vosges durant la première guerre mondiale (2ème partie)”, Les combats de la première guerre mondiale en Alsace, Base Numérique du Patrimoine d’Alsace, 11 December 2015 [link]

Provost S. 2016a, « La marqueterie, un art de guerre des Établissements Gallé », Le Pays Lorrain, 97, 2, p. 139‑148.

Provost S. 2018c, « Quelle direction artistique pour les Établissements Gallé après 1914 ? Les relations de Paul Perdrizet avec les artistes Gallé », in Gril-Mariotte A. (dir.), L’artiste et l’objet. La création dans les arts décoratifs (XVIIIe-XXe siècle), Rennes, Presses Universitaires de Rennes, p. 213‑223, pl. XXV‑XXVIII.

Provost S. 2018d, « Une cristallerie d’art sous la menace du feu : les Établissements Gallé de 1914 à 1919 », in Thomas C. et Palaude S. (dir.), Composer avec l’ennemi en 14-18. La poursuite de l’activité industrielle en zones de guerre. Actes du colloque européen, Charleroi, 26-27 octobre 2017, Bruxelles, Académie royale de Belgique, p. 105‑118.

Thomas V. 2014 : Valérie Thomas, « Produire pendant la première guerre. Les “vases de guerre” des Établissements Gallé », Arts nouveaux, September 2014, 30, p. 34‑39.

For an extensive bibliography on the Hartmannsweilerkopf, see this website.

Notes

HDV du Tarn 2022-06-24 lot 342.

As of June 2023, the vase was the property of Mike Moir (of M & D Moir, http://gallecameo.com), whom I warmly thank for his support in this study. All pictures from the vase are credited to him and to Steven Lewis.

This changed during the latter part of the war, when some earlier blanks were enamel painted, but with a very limited output.

For wood marquetries, see Provost 2014 and the text below.

He was the subject of a MA thesis by Noémie Michel, under my supervision, in Lorraine University in 2020-2021: Noémie Michel, Emile Nicolas, acteur de la valorisation des arts décoratifs lorrains, Master 2 Histoire Civilisation Patrimoine, Université de Lorraine, Nancy, 2021. This academic work was based on the archives trusted by Florence Nicolas (whom I thank warmly for her cooperation) in Remiremont’s archives départementales.

Letter from Émile Lang to Albert Daigueperce, 2 July 1915, Gallé-Charpentier archives.

Receipt from Paul Couleru to Claude Gallé, 12 July 1915, Gallé family archives.

“Alas, many heroes have fallen today in their efforts to reconquer the beloved blue line of the Vosges and are buried in the mysterious calm of the great fir forests, which are like temples. The landscape has taken on an even more moving character, as the tombs, with their rustic crosses, arouse in us feelings of regret and mourning. The artist has rendered this with great simplicity, in a large vase topped by the towering peaks of the fir trees. At the edge of the forest, planted on a solid rock, an Alpine man keeps watch, his gaze turned towards the mountain peak, while behind him, tombs remind us that brave men rest here in eternal slumber. It would have been difficult to evoke a more vivid emotion with such simple means. The great natural world, which seems indifferent to human misfortune, needs very little to appear mournful. A few broken branches from her trees and a grave are enough to bring her into harmony with our sorrows.” Émile Nicolas, “Sur quelques vases de guerre créés par les collaborateurs d’Émile Gallé”, L’Étoile de l’Est, 8 August 1915.

Thomas 2014. My thanks go to the private collector for allowing the use of this picture and to the Musée de l’École de Nancy for acting as a go-between and for taking the picture.

Letter from Paul Perdrizet to Lucile Gallé, 28 May 1915, Gallé family archives.

Établissements Gallé, La Ligne bleue des Vosges, 22.5 cm, Boisgirard Antonini, 03-25-2015, lot 144.

The corresponding glass series, if it was ever made, is unknown to me.

Florence Nicolas, “Paul Nicolas, mon grand-père”, in F. Nicolas, A. Chambrion (ed.), Paul Nicolas (1875-1952) Itinéraire d’un verrier lorrain, Musée de l’École de Nancy, 2010, p. 22.

Hervé Donat, Auguste Herbst, un alsacien chez Émile Gallé, 1878-1961, Strasbourg, 2015, p. 8-9.

Provost 2016a.

How to cite this article: Samuel Provost, “Commemorating the war in the Vosges mountains (1915). A hitherto unknown specimen of Gallé’s war vases”, Newsletter on Art Nouveau Craftwork & Industry, no 22, 28 June 2023 [link].