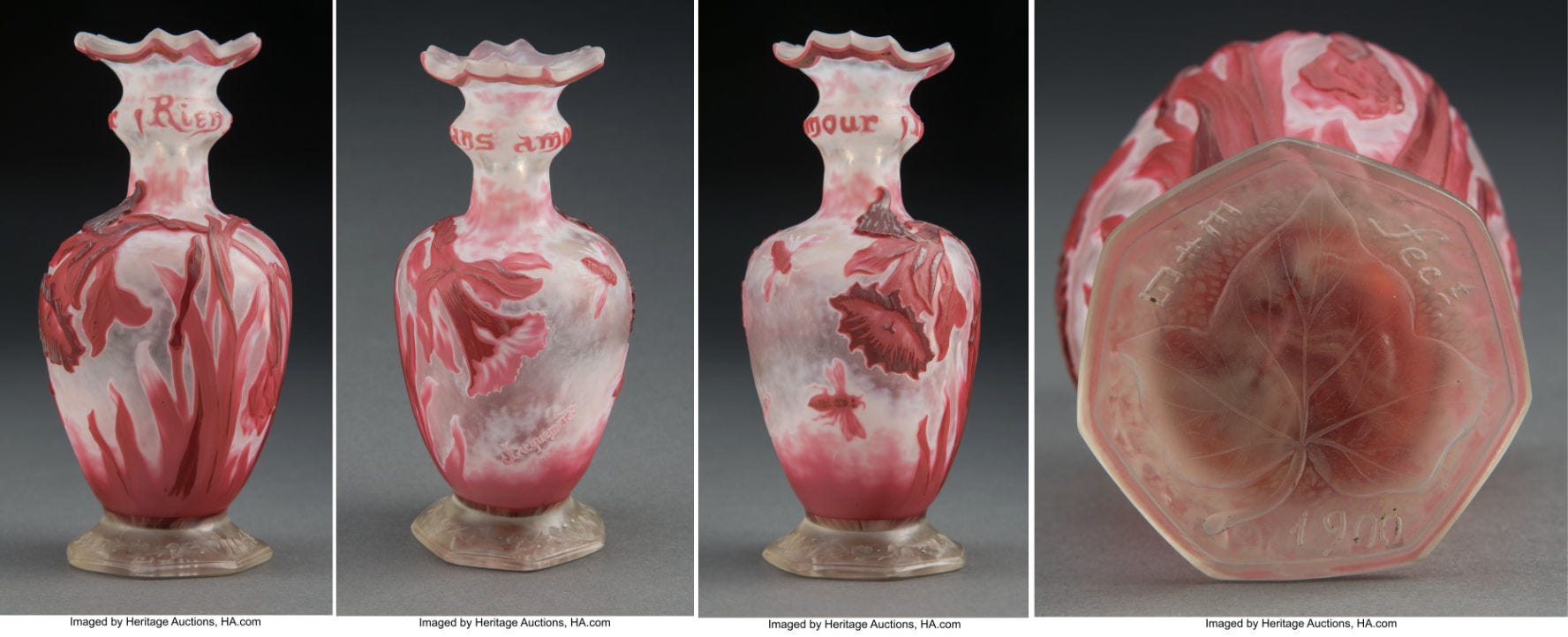

On September 28, 2022, Heritage Auctions sold an impressive but curious wheel-carved cameo vase, bearing the inscription Rien sans amour (“Nothing without love”, probably an abridged version of Victor Hugo’s verse, “Sans l’amour rien ne reste d’Ève”, unless it’s from saint Paul). At first glance, the vase would fit in Gallé’s famed verreries parlantes series, his poetry/motto-inscribed glass creations. But the piece is signed twice, Jacquemard Nancy in cameo on the body, and E☨G fect (Émile Gallé fecit) with the date 1900, in intaglio under the foot. This highly unusual feature presents an interesting conundrum, which the auctioneer chose to solve by describing the artwork as a Gallé vase, decorated by Irénée Jacquemard, in 1900. Jacquemard is indeed a known family name among the Gallé glassworkers ca. 1900-1914: it can refer either to the father, Irénée (1869-…), or to his two sons, Henri (1890-1914), and Gaston (1892-1948), the three of them working as glass engravers. The latter is by far the best known Jacquemard (even though that’s not saying much) because he went on working in Paul Nicolas’ studio after the First World War, while making his own glass artwork: he signed his wheel-carved glass pieces Jacquemard Nancy, in a manner very similar to the signature on the Rien sans amour piece. Here lies therefore the conundrum: if the vase was really made in 1900, as the inscription claims, Gaston Paul cannot be its decorator (he was eight years old at the time). But could his father Irénée have been? And in that case, does it mean that, in the 1920s, Gaston Paul took over his father’s signature rather than making his own? And if Irénée is indeed the vase’s decorator, how come Émile Gallé let him use his signature on a regularly signed artwork?

The Jacquemard, a little known family of engravers in Nancy

To answer these questions requires more information on the Jacquemard family in general, and on Gaston Paul’s work in particular, than is publicly available at this time. For there is precious little known about them: F. Le Tacon seems to have been the only one to look into the matter, for his various lists of Gallé workers. He published several times the same basic information about the Jacquemard, first in L’Œuvre de verre d’Émile Gallé (Messène, 1998, n. 13, p. 229) and in his subsequent works about Émile Gallé1. His source was an Antiques’ seller from Nancy (on 33, Stanislas street at the time), Ladislas Harcos, who wrote in 1997 a short biographical summary about Gaston Paul Jacquemard. A copy of this document can be found in Paul Nicolas’ archives in Remiremont2. As Harcos clearly implies, he mainly relied on the (most probably) oral testimony of Jean Nicolas, one of Paul Nicolas’ sons, himself an artist, who used to work with Gaston Paul Jacquemard in his glasswork studio, up to its closure at the beginning of the 1930s3. This important testimony has to be supplemented by using public records, as well as the Nicolas archives, to piecemeal the Jacquemard family history.

Irénée Jacquemard (Bar-sur-Aube, 1869 - Nancy (?), after 1942)

Irénée Jacquemard, the father, was born on the 10th June 18694, in Bar-sur-Aube, the son of Nicolas Jacquemard, a cabinetmaker. He went on to work in a Paris area glass factory as a glass engraver, in the 1880s. From his address in the Faubourg Saint-Martin street (nr 237), known from his marriage record in 18905, one might venture the hypothesis that he was an employee of the nearby Cristallerie de Saint-Denis, or of another glasswork studio like Prestat6. At the same date, his mother was living in Bayel, in the immediate vicinity of Bar-sur-Aube, the location of a famous cristal making company, the Cristallerie Royale de Champagne. Here lies perhaps the connection between Irénée Jacquemard’s family and glassmaking — it would be interesting to know if he was an apprentice there before moving on to a glass factory in Paris or Saint-Denis.

Whatever the case, he did not stay there long because in 1890 he had an affair with Marie Josephine Duhoux, a young woman from Hennezel, a village in the Vosges. She was not from a glassmaker family, her father being a pellonnier (wood tools' maker), while her mother had been an embroidery maker7. The two lovers had a son out of wedlock, René Henri Duhoux, born on the 22nd April and registered in Hennezel’s civil registry under his mother’s name, without a father. Six months later, however, on the 20th October, Irénée Jacquemard married Marie Duhoux and officially recognised René as his legitimate son, settling in his wife’s home village, Hennezel, where he went on working as a glass engraver.

![The Cléray glass factory in Hennezel, 1897, Image 'Est, FI-0607-6119 [online] https://www.image-est.fr/fiche-documentaire-verrerie-hennezel-1442-20218-2-0.html The Cléray glass factory in Hennezel, 1897, Image 'Est, FI-0607-6119 [online] https://www.image-est.fr/fiche-documentaire-verrerie-hennezel-1442-20218-2-0.html](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!_DKO!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F509d6590-2ce8-46b2-a0c1-a08a74c9d8bf_2910x2148.jpeg)

It’s worth noting that Claudon, Théodore Legras’ birthplace is a mere 9 km away from Hennezel-Clairey, in the same forest of Darney, a major glassmaking center in the Vosges area, going back to the 15th c. In the late 19th c., an important glass factory was located in Clairey, a hamlet on Hennezel’s communal territory. The 1896 census registers the Jacquemard family as living in the Quartier de Clairey, with their four children, Henri (b. 1890), Gaston (b. 1892), Marcel (b. 1894) and René Marie (b. 1895)8. Like most of his neighbours, Irénée Jacquemard is then working for the local Société des verreries de Clairey, which had recently changed hands, after his former owner, Henri Cuchelet had declared bankruptcy9. Is it because of this economic uncertainty? The family moved a few years thereafter to Nancy, where Irénée Jacquemard entered the service of Émile Gallé. Harcos gives 1906 as the date of their arrival in Nancy, which Le Tacon amends as 1901, when in fact it could not have been earlier than April 1897 (when their last son Maurice was born in Hennezel) nor later than July 1898: on the 26th July, Irénée Jacquemard registered his newborn daughter, Yvonne, in Nancy – she lived only two weeks, passing away on the 10th August. The city civil registry lists the family as living in an apartment on 89 avenue de la Garenne, on the same street as the Gallé factory (number 39), where Irénée was employed as a glass engraver – his wife was then the stay-at-home mother of their five young children.

At least another glassworker in the Gallé factory was coming from Hennezel, Ferdinand Villemin (b. 1881), and many more were coming from the surrounding Vosges district: this area was one of the main workers’ pool Émile Gallé drew upon to build his business in Nancy. From — presumably – Bayel to Saint-Denis, then to Hennezel and finally to Nancy, Irénée Jacquemard’s early career moves provide a good illustration of the glassworkers professional mobility, between some of the most prominent glassmaking centres in France at the turn of the 20th c. — the Southern Vosges, Paris, and Nancy.

Very little is known about Irénée Jacquemard after 1901, including the date of his passing10 or his possible participation in the First World War – in 1914, he would have been still young enough to be enlisted in the reserves of the territorial army. He seems to have stayed in Nancy after the war, but not with Gallé: the 1921 and 1926 census still find him living in the same building, in avenue de la Garenne, but the latter document lists him as working as a glass engraver for Daum. This comes as a surprise, given the cold relationship – to say the least – between the two major art glass companies in Nancy. But Irénée Jacquemard’s departure adds up to the already well documented steady flow of talented designers and workers away from Gallé in the immediate aftermath of the war. Many of them chose to join Paul Nicolas in the venture he began, in September 1919, with the support of the Saint-Louis glass company, as we’ve seen in a previous article : such was the case of Irénée Jacquemard’s second son, Gaston (see below), but also of one of the neighbours in their apartment building, François Florentin, also an engraver. Why didn’t Irénée join them and picked instead Gallé’s arch rival? The answer lies beyond our documentation for now. It’s worth noting though that, unlike in other years, the 1921 Nancy census list fails to name the employer (save for self-employed workers) and gives only the job title of the inhabitants. So, we do not know from this source whether Irénée Jacquemard was already working for Daum or for another company in 1921 – Gallé, but probably not Nicolas, since his name is absent from the preserved workers register for 1919-1920.

In his biographical summary, Harcos does not mention if Irénée Jacquemard had ever made his own signed art, implying that all Jacquemard-signed glass pieces were made either by Henri or Gaston, Irénée’s first two sons. It would be somewhat surprising if that was the case: one would expect Irénée to have shown the way, especially since the practice was so common among glassworkers. What this does suggest at the minimum is that Irénée Jacquemard did not have a known specific signature and that no piece of art glass can be readily attributed to him.

Henri Jacquemard (Hennezel, 1890 - Burthécourt, 1914)

The Jacquemard elder son, Henri (named René Henri Charles from his birth certificate, but simply René in common use), was born in Hennezel, on 21 April 1890, before his parents’ marriage, as we’ve seen. His father got him taken as an apprentice in the Gallé engravers’ workshop at an early age, probably ca. 1904, where he was joined by his younger brother, Gaston, two years later11. There is very little known about Henri Jacquemard because his career was cut short by his death on the battlefield, on August 10, 1914, in Burthécourt, during one of the early forays of the French army over the German border, less than 30 km East of Nancy.

Being the first enlisted Gallé worker to get killed at the enemy meant that the news of his death was quickly shared among the factory’s management and his colleagues. Paul Perdrizet, who had taken over the direction after Henriette Gallé’s death (his mother-in-law) three months earlier, tersely wrote to his wife, Lucile Gallé, on the 28th August: “Un de nos bons décorateurs, Jacquemard, tué”.12 So, Perdrizet knew of Jacquemard as a good engraver, but, significantly, he had to make this precision to his wife – who, therefore, would not have known him from the name alone. Moreover, Perdrizet did not identify him as the son of another more senior Gallé employee, the way he would have done for someone else: in the same letter, he refers to the “fils Hestaux”, the “fils Lang”, not needing more precision. This suggests the Jacquemard, as a family, were not really on the radar, so to speak, of the Gallé management, and that Irénée was not recognized as one of the main human assets of the company.

In October 1914, Hubert Roiseux, a painter-decorator, and the son of Julien Roiseux, the Gallé chief glassblower, wrote to his friend and fellow decorator Jean Rouppert to give him some news about the factory: “Nous trouverons beaucoup de manquements quand nous rentrerons, le fils Jacquemard est tué, son frère grièvement blessé (…)”13. Hubert Roiseux himself would not actually come back, getting killed too on the 11th June 1918. The “severely injured brother” he alludes to must be Gaston because he’s the one he would have known from the Gallé factory. A third brother, Marcel (b. 1894 in Hennezel), also died later, in September 1917, in the military hospital of Bar-le-Duc, from injuries sustained in combat. But he was an adjunct school teacher in Champigneulles14, and he had nothing to do with the Établissements Gallé — Gaston was the other Jacquemard son known to Roiseux and Rouppert. The Jacquemard family thus paid a heavy tribute to the war, with two dead and one wounded from their four sons — the fourth, Maurice (b. 1897 in Hennezel), owing his good fortune in part to the fact that his abilities led him to serve as a plane mechanic in the 79th air squad from 1916 to 191815, and, therefore, that he didn’t see any trench warfare.

Henri Jacquemard’s death resonated in the Gallé circle because he was the first among many to die, and these disappearances foretold significant changes when the peace would come back: Paul Perdrizet recognised as much, in the short speech he had Emile Lang deliver in his stead (being mobilised, he was unable to attend), as a eulogy for Ismaël Soriot’s funeral, on the 25th February 1915. Although Soriot had died from illness, the speech was the occasion to memorialise the nine Gallé workers killed at the enemy since August 1914, and Henri Jacquemard among them. Others would sadly follow.

Despite getting killed at 21, Henri Jacquemard left some glass artwork, according to Ladislas Harcos, with a mention of a paper weight with a butterfly-themed decor. This would suggest the same kind of Art Nouveau and Gallé inspired artwork his brother Gaston is also known for.

Gaston Jacquemard (Hennezel, 1892 - Nancy, 1948)

Gaston (short for Gaston Paul) was the second of the five children of Irénée Jacquemard, but the only one beside Henri to follow his father’s footsteps in the Gallé factory, also as an engraver. He served with distinction in the infantry during the First World War, being severely wounded in the 1914 Fall, as we’ve seen from the testimony of Hubert Roiseux: he was awarded both the Croix de guerre and the Médaille militaire for his service16. Fortunate enough to survive the conflict, he chose not to return to Gallé, but he left for Paris, where he spent two years (1919-1920) with an address on Alésia street, in the 14th Arrondissement – faraway from his father’s old neighbourhood. Ladislas Harcos, who provides this bit of information, makes the hypothesis that Gaston was following his father’s advice — perhaps to hone his engraving skills in a Parisian glass studio. It’s worth noting, although it probably is only a coincidence, that the famous stain-glass artist Jacques Gruber moved in Paris in 1920 where he opened his studio in the adjacent Villa d’Alésia. So, there were glassworkers and artists from Nancy in the neighbourhood.

According still to Harcos, Gaston Jacquemard came back in Nancy in 1921 (although the city census from that year registers him as “absent” in his father’s home where he was officially lodged). He was then recruited by Paul Nicolas, whom he knew well from before the war, when they were both employees of the Établissements Gallé. His decision not to go back to the Établissements Gallé mirrored his father’s, and it was probably because he felt, as an artist, a deeper connection with Paul Nicolas than with the mass production-oriented Gallé management led by Paul Perdrizet. Gaston Jacquemard remained a trusted collaborator and a friend of Nicolas throughout the 1920s and early 1930s: he was the last employee Nicolas had to let go, when he closed his studio in 1934, because of the economic crisis.

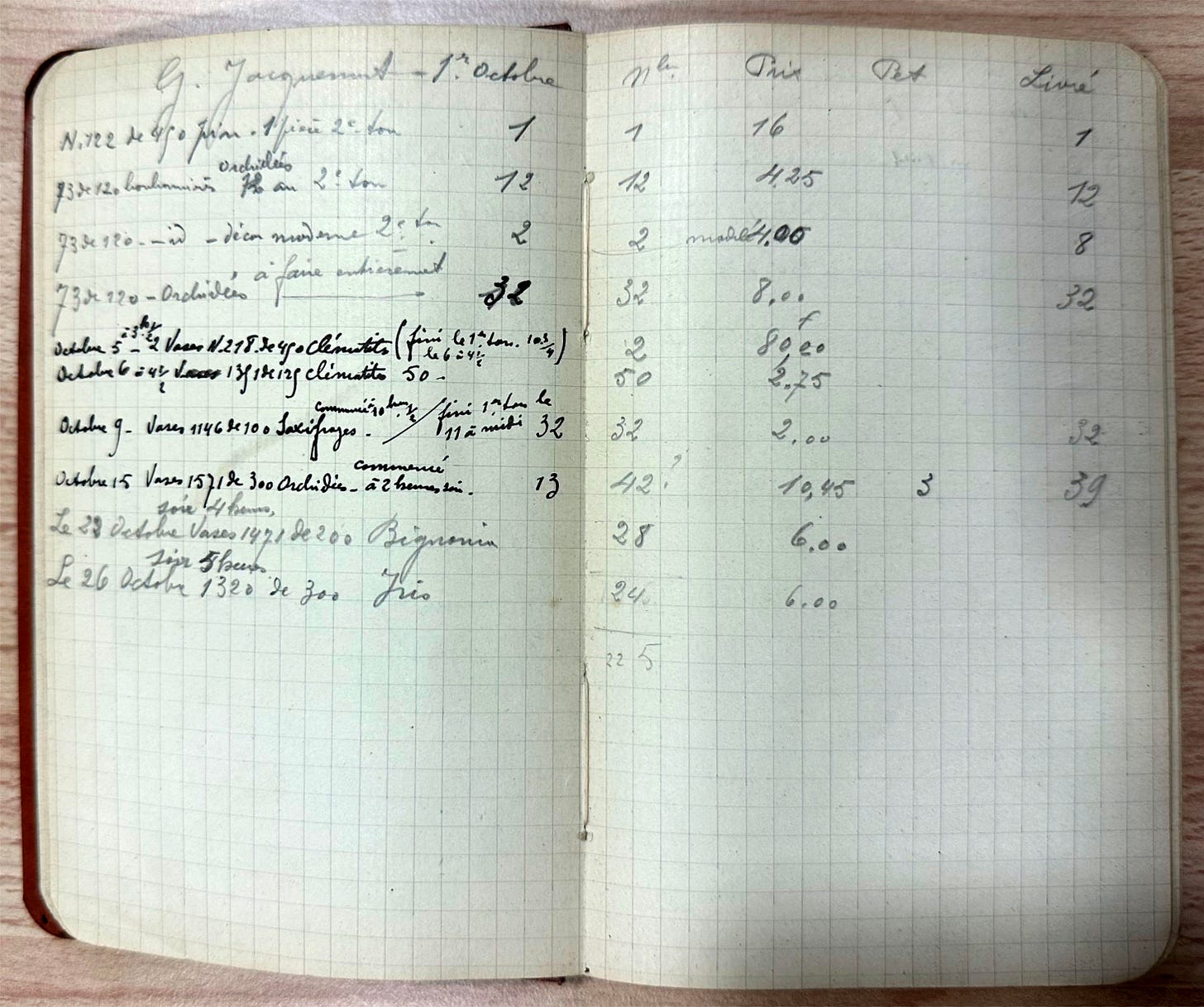

This narrative is corroborated by some archives from Paul Nicolas. One of his notebooks, kept in the Remiremont city archives, contains six pages filled in with lists of glass pieces given to Gaston Jacquemard to be decorated. The lists are detailed with the number of pieces, their decor, size, shape, and their price. The wage system and the work organisation in a cameo glass studio would warrant an article in their own – which Nicolas and Gallé archives make possible. So, without going into too much detail for now, this document confirms that Nicolas carried on for the most part in his glass studio the working structure he had known in the Établissements Gallé. Workers were paid by the piece and expected to deliver a quota of finished objects. An overview shows that over three months, in September-November 1926, Gaston Jacquemard decorated about 400 objects, mostly candy boxes, vases and lamp feet, with a dozen or so different patterns, Vine mostly, Clematis, Orchids, and other botanical themes, but also a “décor moderne” that must refer to some Art Deco style theme (on candy boxes). By the look of it — the number of pieces, the type of object and their shape –, he was therefore primarily working as a painter-decorator for making acid-etched cameo glass pieces, or perhaps as their polisher, but not as a wheel-carver. The price he was paid (presumably) as well as the sheer number of items make it impossible that these were wheel-carved. This underlines a point we’ve already made in examining the beginning of Paul Nicolas’ venture: despite his artistic aspirations, Nicolas’ studio was still a commercial business and his dependence on Saint-Louis to provide him the blanks he needed meant he had to reach a certain output.

The limited number of preserved documents pertaining to Jacquemard’s role in the Nicolas studio does not allow determining if he was a continuously full-time employee there, over the 1921-1934 period, or not. What’s clear from his signed artwork, on the other hand, is that he had some spare time that he could use in this manner. As Harcos points out, setting up one’s own little art glass studio is straightforward and relatively cheap, if one works exclusively with the cutting wheel, from glass blanks purchased elsewhere. This explains why so many big glasswork houses’ decorators could make their own pieces and dream of going fully independent. Gaston Jacquemard was following this template, buying blanks from the Cristallerie de Saint-Louis, and perhaps from other ones. The Saint-Louis link was of course the most straightforward one, since Paul Nicolas was under contract with them as well. Harcos claims, most probably from Jean Nicolas’ testimony, that Jacquemard even assisted to the glassmaking in Saint-Louis, telling the glassblower the shape and the colour scheme he desired for his creations. Again, he was following Paul Nicolas’ lead, with the difference that Nicolas was proficient with the glassblowing pipe and that, in the later stage of his studio’s existence, he was making his own blanks. So, it’s probably not a stretch to envision Paul Nicolas and Gaston Jacquemard going and working together in the Saint-Louis glass factory to get their blanks.

After the closure of the Nicolas studio in 1934, Gaston Jacquemard changed course and, at the age of 42, left the art glass-working trade altogether, gaining employment in the photoengraving workshop of the local newspaper, L’Est Républicain, where he stayed until his death in 1948. We do not know if he kept working on his personal creations in his spare time.

Not much is known about his personal life. He stayed in his father’s apartment until 1924, when he married Renée Hélène Henry (on the 26th April), the daughter of a butcher from Givet, in the Ardennes17. He divorced her in 1929 – they apparently did not have any children – and he did not remarry. Gaston Jacquemard died at 56 only, and Harcos suggests that it was from a glass-working related illness, perhaps some kind of lead-poisoning from his years as a wheel-carver. His death notice was put up in the Est Républicain on the 10-11th July 1948 by his surviving brethren, Maurice and Renée. The lack of a descendance might explain in part his falling into oblivion.

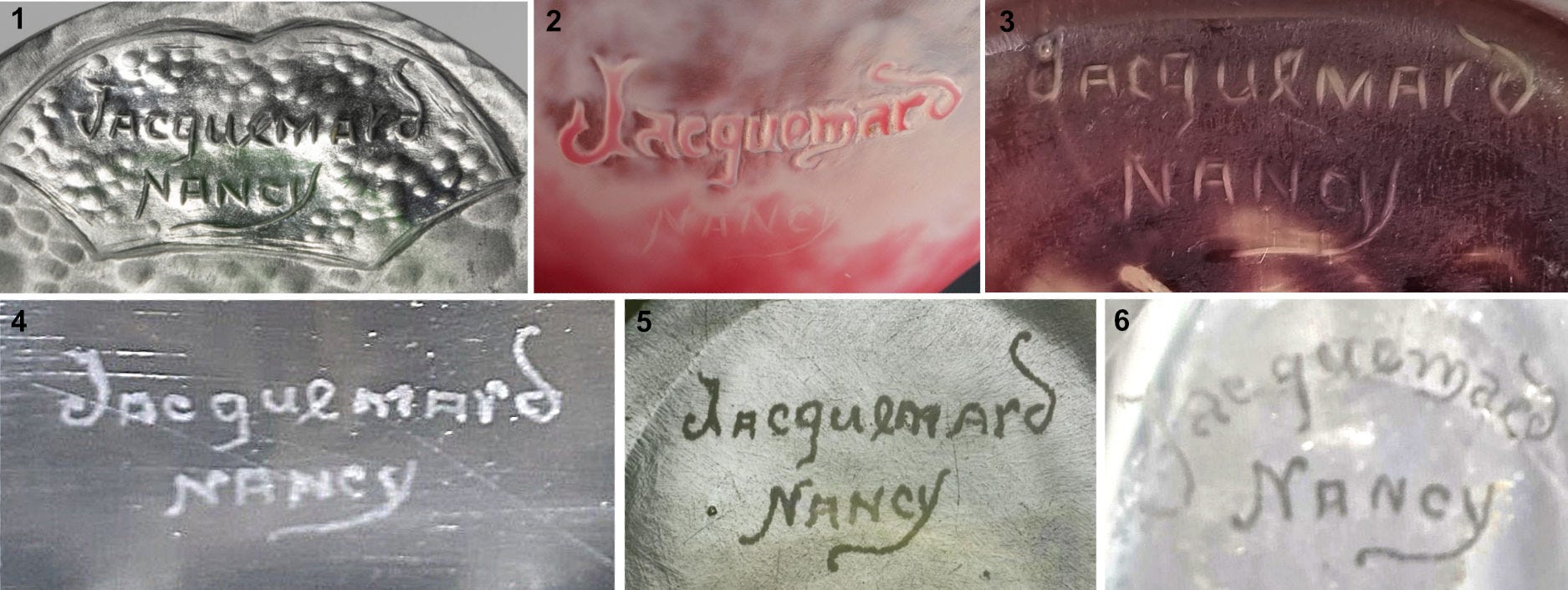

Gaston Jacquemard’s glass art

Jacquemard’s works are very rare, probably all unique pieces of art. There is a small modicum of uncertainty regarding the attribution of some to Gaston or to his brother, René, or even, perhaps, to their father, Irénée, given that all identified pieces bear only the family name. Ladislas Harcos mentions that Gaston Jacquemard could also sign with his initials alone, but I could not locate such pieces: I would be grateful to readers who would have knowledge of such works and would be willing to send some pictures of them.

As it is, the small corpus of available pieces all feature a very similar “Jacquemard / Nancy” signature –for instance the way the letters “d” and “e” have the same peculiar shape. There is little doubt they belong to the same group, and so, unless the three Jacquemard developed a detailed common signature (which seems possible but unlikely), all these pieces come from the same engraver. They can be divided into three subgroups:

Clear glass flasks, signed Jacquemard Nancy on the bottom, engraved in intaglio with a decor mixing small birds or large flying insects with flowers or leaves, covering the entire body of the piece. An inscription runs across the lower body, a motto-like quote from a renowned author, often borrowed from Gallé’s verreries parlantes. The flask’s stopper is decorated too with a related symbol. Both flask and stopper are identified and paired by a unique serial number, which gives an idea of the number of different pieces made by Gaston Jacquemard. Our sample has number 41, Pour bonheur, and 53, Une seule justice pour tous. Harcos had number 40 (no quote given).

A cameo (2-layers) glass flask with a matching stopper, featuring the same kind of decor as the clear glass ones, signed in intaglio on the bottom and also with an intaglio inscription on the body (“Un souvenir”) — a more dedicatory one than a quote.

Cameo multilayered vases with landscape or botanical patterns, without inscription on the body, represented here by a strange but ambitious Cyclamen vase (a marriage of parts?), a green vase featuring a river landscape with a windmill in the background, and a green flower with butterfly vase – the last two vases coming probably from the same batch of blanks, given their matching colours and material – all three signed on the bottom.

The common denominator for these art works is foremost that they are wheel-carved, and not acid-etched. And that was indeed a characteristic of Gaston Jacquemard’s art, according to Ladislas Harcos / Jean Nicolas. Second, the influence of Émile Gallé’s art is striking, both through the choice of decorative themes (large insects among flowers) and the use of inscriptions. But the style is distinctive enough, and more akin to the Établissement Gallé’s naturalism than to Émile Gallé’s poetic stylisation of the botanical shapes. There is also a lack of nuances or research in the pieces’ material compared to Émile Gallé’s, the consequence of working from ready-to-be-engraved blanks for the most part. This is especially true for the clear glass series and the landscapes ones. But then, Gaston Jacquemard did not have the full apparatus of an art glass company at his service. And within these limitations, his work remains nothing shy of remarkable.

The Rien sans amour vase: Irénée, Gaston Jacquemard or Gallé?

Going back to our original question, could Irénée Jacquemard have been the engraver who wheel-carved the Rien sans amour vase ? In 1900, he was already part of Gallé’s team, but he was a relatively new recruit and not his leading engraver (that was Ismaël Soriot). Coming up from the Clairey glasswork factory, working for Gallé was a big step-up, but no doubt requiring some adjustment. So, it is extremely doubtful that Émile Gallé would have let him sign a piece with his name on the body. The number of signed artworks bearing the name of the designer beside the Gallé signature is ridiculously small: a few works by Victor Prouvé, Louis Hestaux, Auguste Herbst, or Rose Wild18, all major designers and personal collaborators of Émile Gallé. Irénée Jacquemard did not belong to that category. Technical collaborators, like the painter Émile Munier or the glassblower Julien Roiseux could be awarded medals in the major exhibitions19, on the strength of Émile Gallé’s recommendations, but they did not add their signature to the artwork, at least not to the official pieces. Of course, as it’s been already noted, many Gallé workers made their own art, in their spare time, whether at home or in the factory, like Georges Ferry or Jean Rouppert. But these pieces could not be signed Gallé as well. The Jacquemard Nancy signature fits perfectly within this model of personal artwork from ambitious and/or bored decorators in the Gallé workshop. It is, on the other hand, incompatible with the Gallé signature. Why would Jacquemard (father or son for that matter) take the trouble of adding the Nancy location after his name, if the vase was already signed Gallé? This does not make sense at all. The explanation of this double signature lies elsewhere.

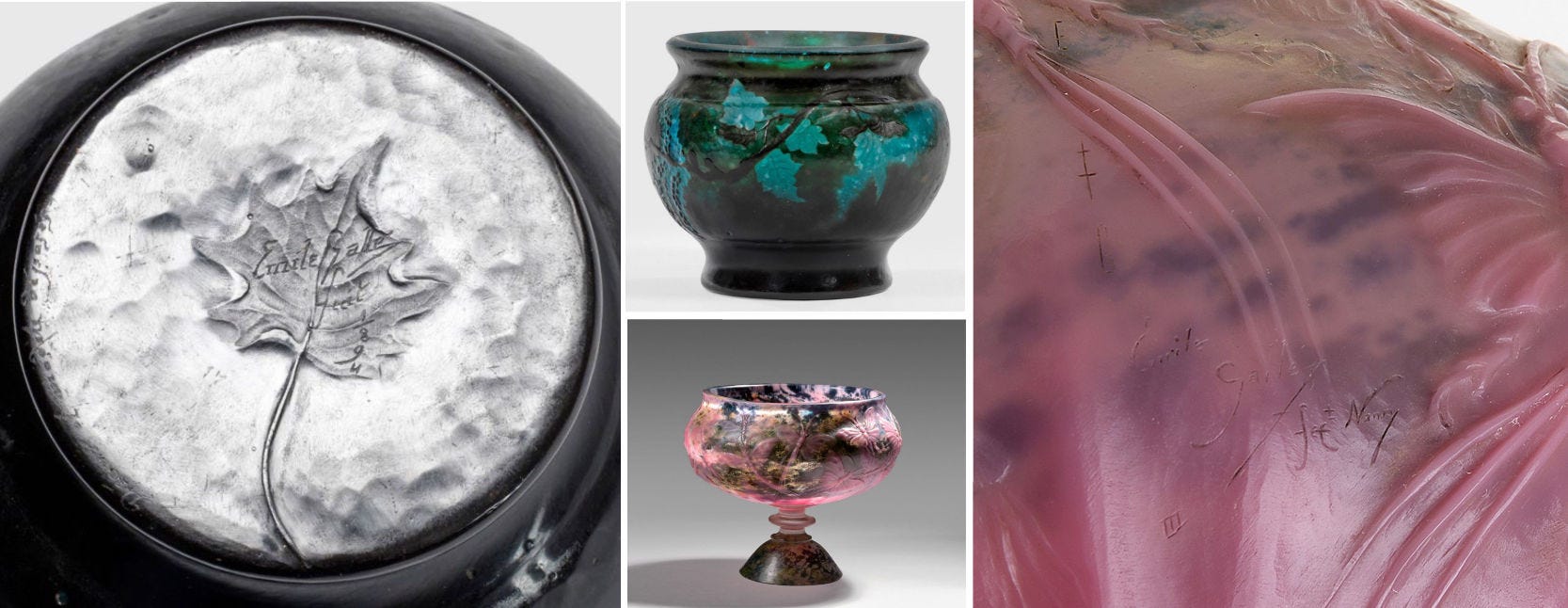

Up to this point, we have taken the Gallé signature at its face value, as a genuine one. But is it really? The combination of the E☨G monogram with the verb fecit (“[he] made”) strikes as an unlikely one. The latin locution means to indicate the personal involvement of the artist. The verb is thus always preceded by a proper name, be it “Émile Gallé” or simply “Gallé”, rather than a monogram, and never alone. So the full name is missing here. Besides, the use of the E☨G monogram as an element of the Gallé signature is a very rare occurrence after 1890 – as is also the Gallé fecit inscription, often replaced by the various modèle déposé patent warnings. Finally, the 1900 date’s design looks quite awkward, a far cry from the elegant curved script, typically a vertical one, that adorns the 1900 art pieces — the zeroes do not even have a closed complete shape here. In fact, the whole inscription under the base has a look of hesitancy, hard to reconcile with a master engraver’s work.

The idea has been floated in a discussion over the vase that its foot might have been a replacement for a damaged original. I do not think one can make this determination over pictures only, and the transition between the foot and the body looks quite smooth. It would have been an exceptionally delicate operation anyway. But whether the foot is original or not, the Gallé signature it features has too many inconsistencies to be authentic. It is almost certainly a forged one, engraved to add value to a vase whose maker’s name was deemed too obscure compared to Gallé’s. Examples abound of this practice, especially at the height of Gallé’s market value in the late 1980s and early 1990s. It follows, as a provisional conclusion, that if the 1900 inscribed date and the Gallé signature are the only arguments to identify the Jacquemard of the second signature as Irénée, then they fail; the vase could as well be Gaston’s work.

The source of inspiration for this ill-advised addition to the Jacquemard vase is easy to surmise, too. Rien sans amour was a motto used by Émile Gallé for a translucent glass enamelled series with various heraldic patterns, in 188620. It was a very successful series, considering the number of surviving specimens, made from white, green or smoked glass. Émile Gallé decided to give it another run, and he ordered, in 1899, a reedition of the series for one of the many Paris 1900 exhibitions, L’histoire du verre au XIXe siècle. These Rien sans amour vases reprise one of the original shapes (there were also matching flasks) and decor, with additional enamelled inscriptions on the body, giving both the dates for their making (“Réédité par Gallé en sa Cristallerie à Nancy 1899”) and for their exhibition (“pour l’histoire du verre au XIXe Se Expos. Univ. 1900”). On the vase’s wide neck, a third inscription, in Latin, reads “E☨Gallé dlt”, i.e. the shorthand for É[mile] Gallé delineavit” (“Gallé designed [the original]” – the technical expression found on reproductions), a rarer substitute for ”Gallé fecit”21. This underlines the observation made above that the E☨G monogram could not stand alone with the latin verb, but that the name Gallé had to be written in full.

It would seem quite out of practice for Émile Gallé to borrow a motto he had already used for a popular series, the same series he was reediting for the Paris 1900 exhibition, and to apply it to a wholly different, in technique as well as in decor, artwork the same year. But on the other hand, as we’ve already seen from previous examples, Gaston Jacquemard found some inspiration in Gallé’s verreries parlantes to the point that he was not hesitating to borrow some of his quotes, including “Rien sans amour”, as it was already mentioned by F. Le Tacon22. The wheel-carving, the simple colours, the prominent flying insects are all hallmarks of Gaston Jacquemard’s style. This strongly suggests that he was indeed the creator of this cameo Rien sans amour vase. His reprisal of a famous Gallé motto (probably after Victor Hugo’s verse) could be seen as a not very subtile hommage to the master : it made all too easy the later forgery of an additional signature, for Émile Gallé, for which the counterfeiter simply borrowed elements from the inscriptions on the original Rien sans amour series (the monogram and the latin abbreviation). As it is often the case in such endeavours, his undoing was that he misunderstood his model.

© Samuel Provost, 28 February 2023.

Appendix: The Jules Jacquemart vase (?)

I would be remiss not to mention another vase that bears many similarities with the Rien sans amour Jacquemard Nancy vase. This another wheel-carved verrerie parlante attributed to Émile Gallé, and signed “Émile Gallé fect 1895” under the base. It was sold by Rago Auctions, on February 27, 2016 (lot 468), with an attribution to Émile Gallé, who would have made it as a tribute to the artist Jules-Ferdinand Jacquemart. The inscription runs on top of the neck and is rather long: “Dis aux petits que les étés sont couverts de colchiques des Alpes. J. Jacquemard”. The auctioneer misspelled several words in this transcription (“le” for “de”, “colchiqué” for “colchiques”) on the visible part of the inscription in the available pictures online. Confidence runs therefore low for the invisible part, including, unfortunately, the name Jacquemard. Is there really a “d” and not a “t” at the end (in which case it cannot be the Jules-Ferdinand Jacquemart (1837-1880) the description relates the vase to)? Is there also an initial J before the name? On a previous sale, with an even more faulty transcription, the reading was an initial L. Without some proper pictures of the inscription and the name, it is therefore impossible to make a definitive attribution. However, the decorative pattern and other characteristics of the vase are compatible with a Gaston Jacquemard work, all the more since, here again, the Émile Gallé signature is perhaps not entirely convincing.

[EDIT: on March, 7th, 2023, addition of new pictures from the Remiremont museum, courtesy of its director, Aurélien Vacheret, with my warmest thanks for his help on the matter; addition of the attribution to Gallé by Rago for the vase in the appendix.]

Footnotes

Le Tacon and De Luca 2000, p. 22 ; Le Tacon 2004, p. 259.

The 5-pages typescript document is unsigned but its title and content match the reference as well as the information given by F. Le Tacon in his books. The document is kept in the file about the main Nicolas exhibition from 2010, and it was probably provided to the organisers by the author or by F. Le Tacon. Archives municipales, Remiremont, Fonds Paul Nicolas, 29S17.

Jean Nicolas was a graduate of the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Nancy, where he majored in the engraving section, in 1930. He went on working for his father until 1934, when he married one Anne-Marie Leroy, the sister of a sculptor, Marc Leroy. The couple settled in the Meuse where they had a ceramic studio. Childless, they adopted a young Hungarian sculptor, Jean-Pierre Farkas — through which Jean Nicolas may have met Ladislas Harcos, one would guess. Nicolas and Chambrion 2010, p. 25.

Harcos erroneously gives the date as the 18th June 1870, followed by Le Tacon (op. cit.).

Registre d’état civil, Hennezel (Vosges), 4E242/13-40414, 1890, nr 61 (available online).

Harcos duly notes, as a matter of comparison, that the celebrated glass artist Auguste Heiligenstein began his career, as an apprentice, in the Legras factory in 1904, before moving on to the Prestat glass studio, on this Faubourg Saint-Martin street. See also Olland 2014, s. v. Auguste Heiligenstein (1891-1976), p. 177.

Harcos notes, however, that Marie Duhoux’ own mother was working as “a painter”, which might be a shorthand for painter on glass.

Archives départementales des Vosges, 6M797-108078 Hennezel (Vosges, France) 1896.

“Vente par suite de liquidation judiciaire de l’usine des Verreries de Clairey et d’un étang”, L’Est Républicain, 22 January 1893.

It would have been after 1942 if he died in Nancy, because his name does not show up in the death registry, which is available online up to this date. It was definitely before 1948, because his son’s death certificate does not mention him.

It looks safe to assume that the chronological mistake made by Harcos (presumably following Jean Nicolas’ indications) giving 1906 as the Jacquemards arrival in Nancy stems from a confusion with Gaston Paul enlistment as an apprentice in the Gallé factory.

Letter from Paul Perdrizet to Lucile Gallé-Perdrizet, 28 August 1914, Gallé family archives.

“We will find many missing when we’ll come back, the Jacquemard son killed, his brother severely wounded”: letter from Hubert Roiseux to Jean Rouppert, 24 October 1914, Rouppert family archives.

This is according to his military registry: Toul 1914/514. Being of the 1914 class (reaching his 20th birthday that year), he was enlisted too.

Maurice Jacquemard, Nancy-Toul military registry, Matricule 1917/672.

Information given on his marriage record in 1924 : État-civil de Nancy, registre des mariages pour 1926, number 383.

Nancy, État-civil, marriage registry for 1924, number 383.

See the twice signed Érable vase she designed, in the Musée de l’École de Nancy in 1903 (inv. 990.2.1) : Valérie Thomas, “Une série ordinaire, un thème décoratif unique, décliné dans des formes diverses”, in Verreries d’Émile Gallé. De l’œuvre unique à la série, Somogy, 2004, p. 100.

Both of them were awarded a medal in Paris 1900 Exhibition for instance : Le Tacon 2004, p. 258.

The original date of the creation is known thanks to the register of the applied arts museum in Nancy, whose acquisition committee bought a 1900 reedition : Émile Gallé et le verre, cat. 143, p. 107.

Olland misread "J St” (sic) the “dlt” abbreviation in his transcription of the specimen from his private collection (Olland 2016, p. 151).

Le Tacon 1998, p. 259 n. 13. There’s no indication if this is the same vase or not.

Bibliography

Harcos L. 1997, Gaston-Paul Jacquemard, unpublished.

Le Tacon F. 1998, L’œuvre de verre d’Émile Gallé, Paris, Éd. Messene.

Le Tacon F. 2004, Émile Gallé, maître de l’Art nouveau, Strasbourg et Nancy, la Nuée bleue Éd. de l’Est.

Musée de l’École de Nancy 2014: Musée de l’École de Nancy Émile Gallé et le verre: la collection du Musée de l’École de Nancy, Paris, Somogy éditions d’art, 2014 (2).

Nicolas F. and Chambrion A. 2010, Paul Nicolas, 1875-1952 : itinéraire d’un verrier lorrain [exposition, Nancy, Musée de l’École de Nancy, 6 novembre 2010-13 février 2011], Nancy, Musée de l’École de Nancy.

Olland Ph. 2016, Dictionnaire des maîtres verriers, marques et signatures : de l’Art nouveau à l’Art déco, Dijon, Éditions Faton.

Thomas, Thomson and Thiébaut 2004: Valérie Thomas, Helen Bierie Thomson and Philippe Thiébaut, Verreries d’Émile Gallé : de l’œuvre unique à la série, Paris, Nancy, Gingins, Somogy éditions d’art, 2004.

How to cite this article : Samuel Provost, “Irénée, Henri and Gaston Jacquemard

A family of glass engravers in the Établissements Gallé”, Newsletter on Art Nouveau Craftwork & Industry, no 20, 28 February 2023 [link].