Understanding Gallé labels (II): Fake Gallé labels.

Did the Gallé retail shop in Nancy have its own labels?

Fake labels as authentication markers on Gallé glass.

The first part of this ongoing and long-delayed study of the Gallé labels already highlighted the use of genuine as well as fake specimens to strengthen the authenticity of the glass pieces they were applied to. The matter looks worthy of a further development, since the practice appears to grow by the years, with new attempts at forgery1. Quite understandably, the main label types are the primary targets, i.e. the E5 (EMILE GALLÉ • NANCY • PARIS) and the E7 (ÉTABLts GALLÉ • NANCY • PARIS) ones, as shown in the picture above: the text is the same but the typeface, the design (one encompassing circle only, the lack of dotted lines in the centre), the paper are all different. One case could probably be made that these merely represent genuine variations of the primary types, especially since they appear on otherwise good Gallé glass pieces, like the Mk III-signed river landscape vase above. But the lack of a hand-scripted inventory number – although this number was their purpose to begin with – as well as their rarity (still) rather point to a misguided attempt at forgery.

Another new purported Gallé label screams its fake character. Based on the more uncommon, and a bit mysterious, E4 type (CRISTALLERIE GALLÉ • NANCY), the label appeared recently on multiple Gallé glass pieces – again authentic ones as far as one can tell – in Australia and elsewhere. These glossy stickers look brand new and very different from the original ones (the typeface again, and the colour), so their aspect already left no doubt regarding their authenticity, even when they were wilfully damaged to appear a bit older than they really were. But the forgery was confirmed in a rather farcical way when a collector found, in the bottom of a package from a French antiques’ seller, such a sticker still attached to its paper.

A label for the Gallé historic store in Nancy?

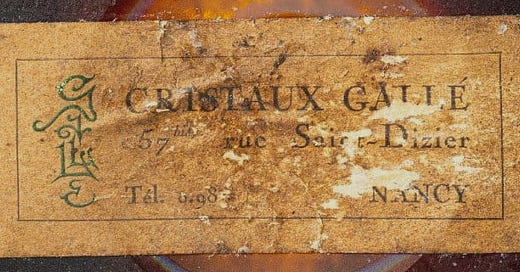

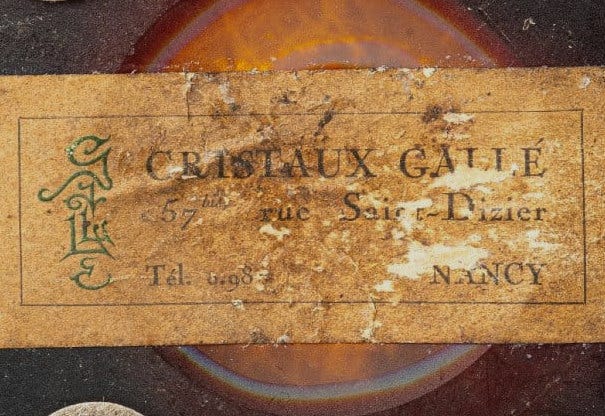

A trickier case of authenticity comes with an extremely rare type of Gallé label. The most recent specimen to emerge is featured on a tall red Roses tube vase, sporting a Mk VI signature (so ca. 1925-1936). The vase’s authenticity is not in doubt. This is a classic decor, well attested in the later 1920s, and the execution looks excellent. The label under the base is another matter, though. It’s a large rectangular yellow paper label, with the following text “CRISTAUX GALLÉ 57 bis rue Saint-Dizier Tél. 0.98 Nancy”, printed in black inside a thinly outlined rectangle, flanked by a drawing of the vertical Gallé Mk IX signature, in green ink. The paper is slightly creased, stained, and shows some heavy wear, with even some damage to the text – in other words, the label looks properly old.

This Gallé label is very different in many ways from the six types I documented in my earlier study. First and foremost, it’s not a factory label. As its text and its layout make clear, its sole purpose is to identify a retail location, with an address and a phone number. As such, it belongs to an entirely different category from the factory issued stickers whose primary function, as we have seen, was to track the inventory, by assigning a lot number to each object, glass or wood. These labels had therefore some dedicated blank space left for writing in the number while the company’s general identification information was left to the bare minimum (Gallé Nancy Paris and its variations) — no address, no phone number. That these factory labels, in their successive iterations, are the only attested types makes perfect sense insofar that Établissements Gallé were only making gross sales, leaving the distribution to a wide network of independent retailers all over the world – whose labels appear quite often next to the factory issued label. Take the Firmin Didot professional directory for Paris in the 1910s, for instance: under the name Émile Gallé, it lists both the official representative address, Albert Daigueperce, rue Richer, and one of the main retailers’ address, Géo Rouard’s A la Paix gallery. The former was managing the depot and, as such, he was not a retailer, and he did not have a distinctive label, in contrast to the latter, who also advertised the Gallé wares in his catalogues as well as in various newspapers and magazines.

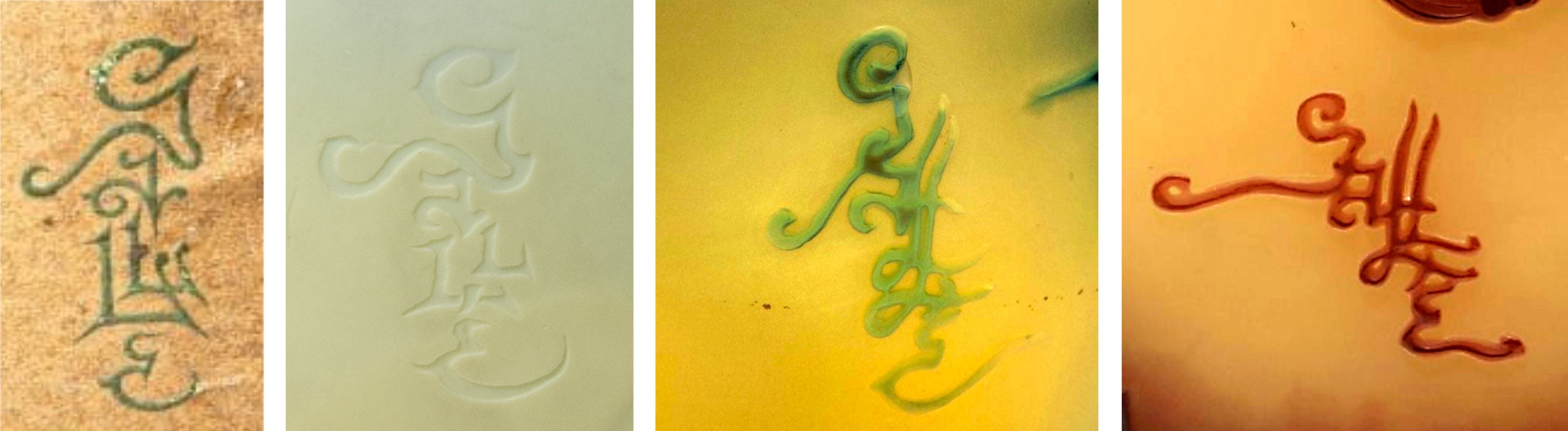

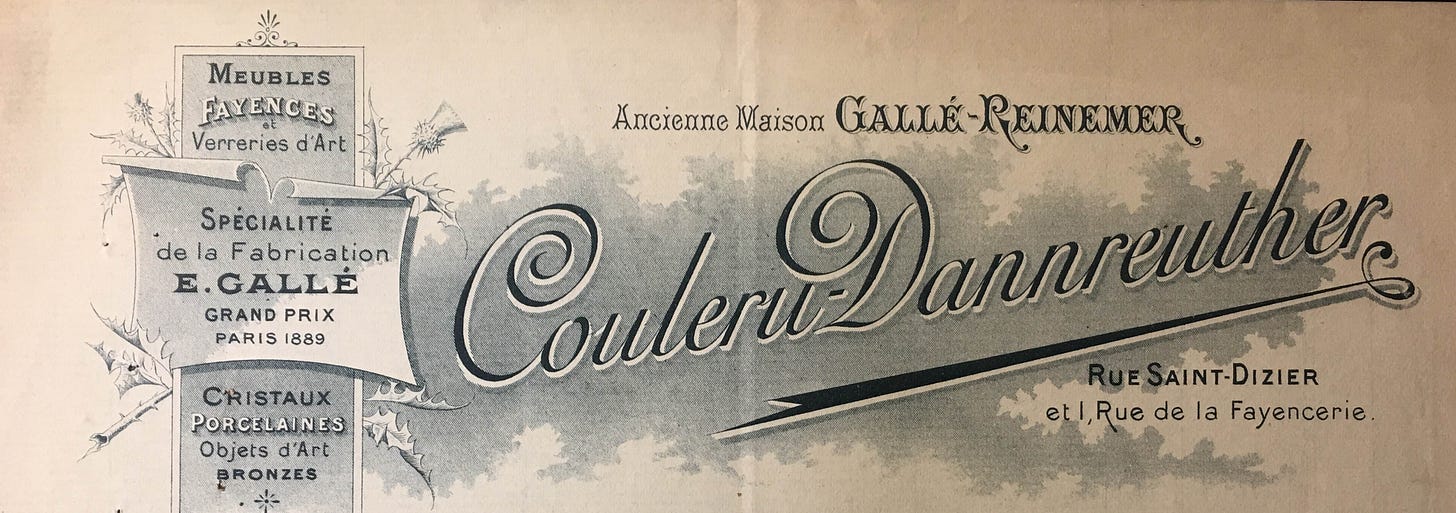

So, in principle, Établissements Gallé had no need for a retailing label, and they do not seem to have had one, as the general lack of material evidence reflects, the exception being this label on the Roses vase that fits the function and warrants further examination. The address it bears is of course correct: it identifies the only retail outlet under Gallé’s management, the historic family store in Nancy. Located at the crossroad of the Saint-Dizier and Faïencerie streets (as shown on the picture above, from 1888), right in the middle of Nancy’s centre town, the shop is frequently referred to by this double address: 1, rue de la Fayencerie and 57 bis rue Saint-Dizier. But the latter street address does tend to prevail in the sources as the main one, since it’s a much more important road. That’s the case, for instance, in Nancy’s professional directory for 1922, where the first company listed under the category Cristallerie, verrerie d’art, éclairage is Gallé. It provides two distinct addresses, 39, avenue de la Garenne for the workshops, and 57 bis, rue Saint-Dizier for the retail shop (see the picture below)2.

This 1922 directory listing also gives other useful comparative information for the label under review: it has a phone number for the workshops (the factory) but not for the shop, raising the possibility that the latter did not have one yet. If genuine, the label, with the phone number, would therefore be later than 1922 – a date that fits the general chronology of the vase bearing the label.

But another titbit of information from the directory raises some doubt on the matter: the shop and the workshops are referred to under the name Cristaux d’Art Gallé (with a capital A at Art) rather than Cristaux Gallé as is the case on the label. The difference is significant, for the Gallé successors (not to mention Émile Gallé before that, of course) held of paramount importance this characterisation in the commercial designation of the company: the Établissements Émile Gallé (before 1925) and then the Établissements Gallé (after 1925) were a Cristallerie et Ébénisterie d’Art. The statutes of the new société anonyme, incorporated in April 1925, make it clear:

La Société a pour objet : La fabrication et la vente de cristaux et meubles d’art (emphasis added).

The emphasis on the artistic merit of their products was of course a matter of prestige and marketing, but it also had real financial consequences, for it allowed the company to evade some industrial tariffs (a matter for a future article). This artistic character was undisputed (except for the critics, of course) and constantly stated in the successive iterations of the company’s letterhead on their official paper as well as on their catalogue’s plates. It seems therefore quite weird that the official label for the retail shop would drop the d’Art qualifier, all the more so since the shop’s name remained, until its closure in December 1935, Émile Gallé - Mobilier et Cristaux d’Art (as shown on the barely legible shop sign on the picture below).

In short, Cristaux Gallé was not the name of the retail shop, and it most definitely was not the way the company wished its clients to think of its products. If it is true that some minor retailers were using Cristaux Gallé as a shorthand for the Établissements Gallé products in their advertisements, one would expect the company to uphold the complete designation on its own marketing material. Besides, given the size of the label, there was ample space to use Cristaux d’Art Gallé rather than Cristaux Gallé, so the discrepancy is hard to explain.

This is not the only puzzling detail on the label. The reproduction of an elaborate Gallé signature next to the shop’s name is even more troubling. This vertical ornamental signature is a well-known one and falls under the Mk IX types in the nomenclature I proposed3. It reprises a signature designed under Émile Gallé, and it sees heavy use, on glass as well as on wood, in the late 1920s and early 1930s, that is in the last period of the factory. I suggested that it was reintroduced as late as 1926 or 1927 (as shown in the signatures’ table), but I would consider today an earlier date, perhaps as soon as the early 1920s, in light of some specimen featured in series introduced at that time. But, then again, those specimens could very well have been made in the late 1920s or early 1930s, given the duration of a production-run for a popular series, so the question remains opened. Whatever the case, the use of this signature is in the right timeframe for a 1920s label.

It remains, however, quite suspicious because of one glaring defect. The particular drawing used on the label misses an acute accent on the E, and the name reads therefore GALLE instead of GALLÉ. On the Mk IX signatures, this accent is always present, as it should be, less this omission changes the name. That’s a detail some forgers – in particular the non-French-speaking ones, we can assume – always have some difficulty grasping. The final accented É is an absolute imperative on the signature’s design. There might exist some rare Gallé glass pieces where it’s missing, but that’s just a byproduct of a poor execution from the workers’ part: the accent has been forgotten or erased accidentally during the manufacturing process (as can be other details of the design), certainly not wilfully omitted. In that regard, contemporary catalogues of Gallé signatures that reproduce some “Galle” (without the accent) signatures drawings are misleading and just show a poor understanding of the signature’s design. In the case of the Mk IX type, the accent usually runs across the second L’s horizontal line, which can make it a little difficult to spot, but it can also stand isolated or a little to the right or left of the letter. Either way, it’s missing on the label (where it cannot be confused with a small brown stain higher, across the first L), and that’s unexplainable. One would expect the Gallé management to carefully review the design of the label, and they could have hardly missed this mistake and allowed it to be printed anyway. In fact, one would not expect the designer in the first place to make the mistake.

I would argue that the use of a signature on a label more probably reflects the fixation of modern-day forgers (as seen for instance on the fake advertisement triptychs) than the practice of Établissements Gallé at the time. The company never used a particular signature as a logo (at least after 1904), quite simply because it adopted the practice of changing it, even so slightly, at a frequent rate. Some photographic plates the company used to advertise its wares (both glass and furniture) to the retailers in the 1920s have thus an embossed logo, which is nothing more than the name Gallé in capitals inside an oval (pictured above), with Nancy added underneath. So, until proven otherwise by some new documents bearing this Mk IX signature as a symbol for Gallé glass, one can remain sceptic as to the authenticity of the label, especially when the faulty design is taken in consideration.

One last detail: the signature’s drawing is printed in green, adding a light amount of colour to the label as well as another small puzzle. By contrast, all the factory labels were understandably monochrome. And given the cost-conscious management of the company, having a colour-printed label looks like an unnecessary expense, even minor as it must have been. And why green? Could it be a reference to the famed Gallé green – a distant memory by the 1920s? It strikes as too cute by half.

One solution to the little dilemma this label poses would be to postulate a disconnection between the factory and its retail store in Nancy when it came to marketing matters, or, in other words, a sufficient degree of freedom to allow the store to print its own labels. This seems impossible, with such a label in the 1900s-1910s, and still highly unlikely, absurd even, for the 1920s-1930s for the following reasons. As I underlined in the study of the Vosges war series, the Gallé retail shop was, in fact, under the independent management of a distant cousin, Paul Couleru, until 1915: up to WW1, the store was still the exclusive retail outlet for Gallé products in Nancy, but it was named after its managers, Couleru-Dannreuther, as invoices from that period can attest. It follows that the label discussed cannot date from before 1915. The shop was then brought back under the close control of the Gallé family and the Établissements Gallé. After the war concluded, it was entrusted to none other than Pierre Perdrizet, a defrocked clergyman and a former Peugeot car dealer, and, above all, Paul Perdrizet’s younger brother. Pierre Perdrizet soon took over the role of main commercial traveller for the Établissements Gallé, but his wife remained the shop’s manager until its closure in 1935. For all intent and purpose, the Gallé factory was therefore running the shop, in compliance of Paul Perdrizet’s policy of cutting the middleman and keeping the selling fees as low as possible. If the label is genuine, it must date from this period, but, as we’ve seen, its existence would demonstrate a degree of autonomy from the factory that does not square with what we know of the Établissements Gallé management at the time.

To summarise, this is an exceptionally rare label for the Gallé retail shop in Nancy, that can only date from the 1920s-early 1930s, given the store’s history. This chronology is confirmed by the vase that features it. However, the label’s text, the use of the Gallé signature as a logo, with a major mistake in its design, raise serious questions about its authenticity. While the rarity could be perhaps explained by the small share of the Nancy store in the overall Gallé sales (it catered mainly to the Nancy area), the other questions remain. If the label is a forgery, on the other hand, that would also explain certain features, such as its large size, that probably would have prevented its use on the smaller glass pieces, and its excessive wear and tear4. It stands in contrast with most known retail labels in both regards. As it’s been suggested5, the label’s size would allow it to hide some undesirable defect, which would be one of the prime reasons to use it, and a different one from the other fake labels we’ve highlighted in the first part of this article.

The question whether the Gallé retail store in Nancy had its own labels remains therefore, at this stage, open, in need of further documents.

© Samuel Provost, 7 August 2023.

Bibliography

Annuaire administratif, statistique, historique et commercial de la Meurthe-et-Moselle et région de Metz, 98e année, Nancy, Imprimerie A. Humblot et cie, 1922.

Provost S. 2019, « De prétendus triptyques publicitaires des Établissements Gallé», Le Pays Lorrain, 100, 2, p. 135-142 [open access link].

Footnotes

In this regard, the Facebook group French Art Glass, run by Mike Moir of M&D Moir, has proved as resourceful as always, with several posts by users signalling new labels. They all have my gratitude for this help.

Available online on Gallica. One has to note, however, that Pierre Perdrizet’s address, the shop manager at the time, is given as 1 rue de la Fayencerie, in the personal section of the same directory – so the two addresses still coexist, for different purposes.

As a coincidence, this is one of the subtypes I made a vector drawing of to use as a logo of this newsletter.

Compared to the well preserved state of the vase’s base, the label does appear to show too much wear and tear, especially since there was no apparent attempt to remove it, which is the usual way a label gets damaged. Otherwise, these labels tend to be almost pristine (except in the case of water-related damage), despite being a century old, because most of the vases rest inside display cases and are not shuffled around. Here the forger, if it’s indeed a forgery, has overdone it – a common mistake.

Steven Lewis, whom I thank for his insight, made the suggestion in the French Art Glass group on Facebook, August 4, 2023.

How to cite this article : Samuel Provost, “Understanding Gallé labels (II): Fake Gallé labels. Did the Gallé retail shop in Nancy have its own labels?”, Newsletter on Art Nouveau Craftwork & Industry, no 23, 7 August 2023 [link].